It seems that some people really want a recession.

The estimates of inflation not falling below 3% until the end of next year has led some commentators to demand higher rates as though there is an ability to have inflation drop quickly while at the same time delivering the hoped for economic “soft landing”.

After the RBA’s decision on Tuesday to keep rates steady, you would be forgiven for thinking that a rate rise is imminent. Other than Peter Hannam, who maintained a level of calm, some media organisations were suggesting rate rises are now much more likely and that there is a sense of doom ahead for inflation.

It might therefore be somewhat surprising to be told that the market’s expectations for a rate rise are actually lower now than before the RBA’s decision on Tuesday.

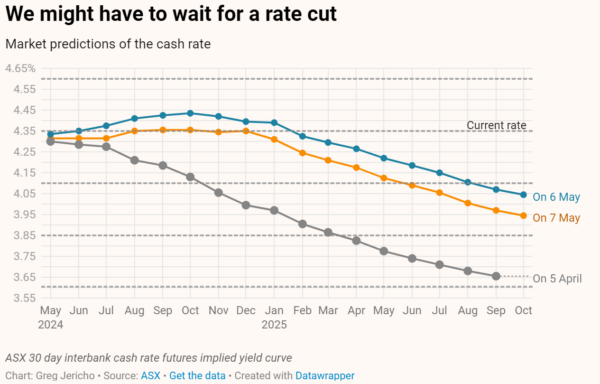

A month ago, I suggested that it was unlikely we would see a rate cut soon. Back then the market was still predicting rate cuts this year; now they are not. Cuts are on the horizon, but probably not until next year:

This is not what those who believe rates need to rise want to hear.

Judo Bank chief economic adviser Warren Hogan has, for example, called for higher interest rates – as high as 5.1%. Hogan last year commented on a scenario in which the then newly appointed RBA governor, Michele Bullock, “must lead the bank in taking the cash rate to a level that will drive Australia into a disruptive recession”. Meanwhile, one academic bizarrely suggested Australians should stop buying things in order to “drive the nation into a short, sharp recession”.

Calling for a short recession for the good of the economy is a bit like calling for a small war to teach another country a lesson. They never end up being small or short and the people calling for them invariably know they will not have to suffer.

It’s why the past year has focused around the desire for a “soft landing”. This essentially involves shifting from rising inflation to low, steady inflation without a recession, and without significant rises in unemployment.

In essence we want to avoid what happened in the 1990s, when killing inflation involved destroying the economy.

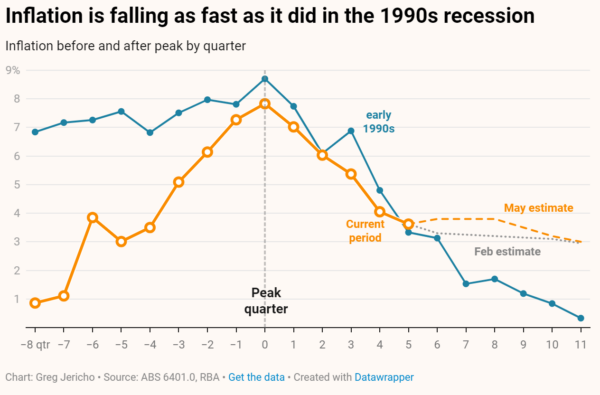

Generally, you want to avoid replicating the 1990s experiences, and yet inflation is falling pretty much in line with the pace of the falls during 1990-1992:

The 1990s was a stark lesson to anyone thinking we can just fine-tune inflation without having to worry about going too far.

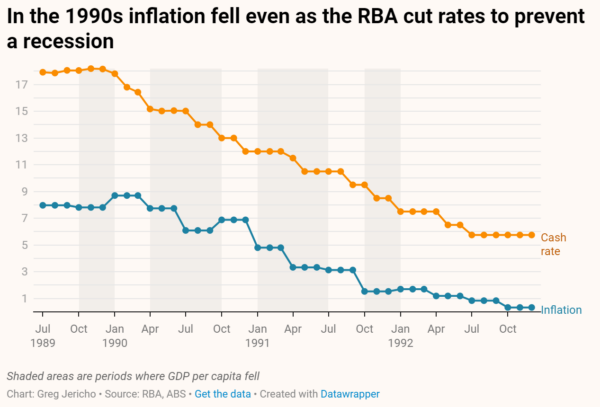

One of the oft-forgotten aspects of the 1990s recession is that when inflation was falling the RBA was madly cutting rates in a desperate (and failed) attempt to prevent a recession:

Throughout 1990, 1991 and 1992 the real problem wasn’t slowing inflation but trying to stave off a deep recession.

It failed.

Inflation, rather than reaching 3% and realising – as though through osmosis – that it should stabilise, just kept dropping – hitting 0.3% at the end of 1992.

The RBA at this point was cutting rates in the hope of raising inflation because inflation below 2% is hardly the sign of a strong economy (something we experienced from 2014-2019 when the RBA kept cutting rates in an attempt to get the economy going).

There has been some commentary that the RBA has never before failed to raise rates when inflation has been this high. The problem with that history is that similarly the RBA has never raised rates before when the economy has been this weak.

In November, when the RBA raised rates to 4.35%, GDP per capita fell 1%.

Prior to last year, the slowest the economy had grown at a time the RBA raised rates was in June 2010 after the GFC. At that point GDP per capita was growing at 0.6% – a pace that is historically weak, but which is faster than Australia’s economy has grown for nearly 18 months:

And is the economy about to rebound?

Well, no.

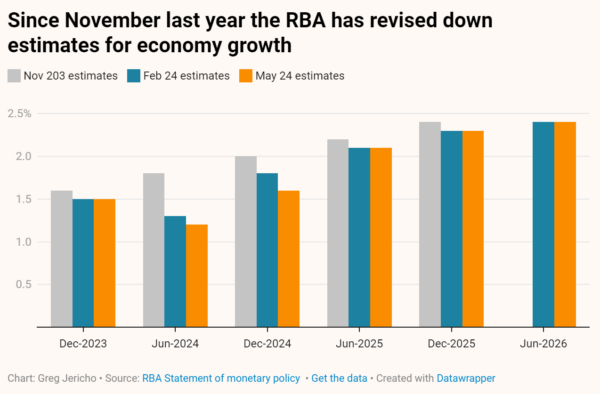

The latest statement on monetary policy issued by the Reserve Bank on Tuesday showed the second lot of downgrades for economic growth since it last raised rates in November:

Bullock in her press conference on Tuesday afternoon was also very careful to note that, while we do have historically low unemployment, many people are struggling.

This was made clear by the weak retail trade figures released on Tuesday, which showed that the volume of retail trade fell for the fifth quarter out of the past six.

And while unemployment remains low, most economists believe wage growth has peaked. Certainly, the average wage growth obtained through enterprise bargaining agreements shows no signs of wages growing faster than last year:

We might be experiencing low unemployment and have avoided a recession despite very fast rising interest rates, but households are letting the government and the Reserve Bank know that they are feeling the pain. They are not spending money in a manner that would suggest there is a strong level of demand in the economy.

Wages are also not rising at a speed that would suggest we are about to embark on the mythical “wage-price spiral”.

Those calling for higher interest rates and for a faster drop in inflation should read about the 1990s recession and not cheer for that experience to be visited upon us again.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Delayed RBA cut is welcome, but borrowers are still lagging

The RBA has cut interest rates – five weeks too late.

BREAKING: Australia’s housing market still cooked

Even the Mathias Cormann-led OECD says the capital gains tax discount and negative gearing are a problem.

Greg’s budget wishlist

The Australian Government can’t afford to do everything, but it can afford to do anything it wants.