40 years on, Whitlam’s vision under threat

- Gough: Advancing equality in Australia

- We all lose from Medibank privatisation

- Coal not the solution to energy poverty

- TAI in the media

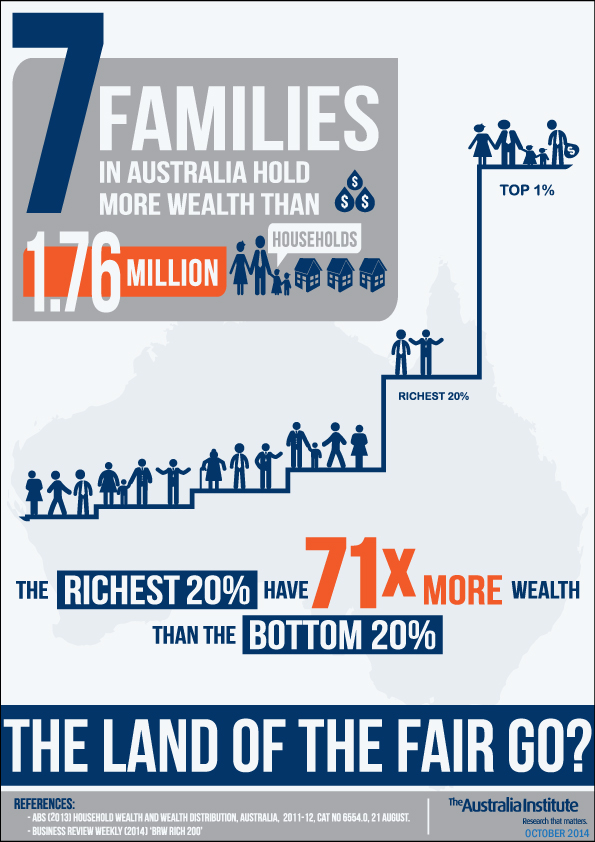

- Infographic

Gough: Advancing equality in Australia

Poverty is a national waste as well as individual waste (Gough Whitlam, 1969 election campaign).

With the passing of former Labor Prime Minister Gough Whitlam this week it is timely to remind ourselves of some of his initiatives and achievements in advancing equality in Australia. Gough Whitlam’s concern with equality is reflected in the mention of the word, or its opposite, ‘inequality’, 17 times in his Policy Speech on 13 November 1972 in the election campaign in which he won government.

Medibank and free education are of course the initiatives that most people associate with the Whitlam Government. Whitlam was fond of saying that before Medibank he paid much less for his health insurance than his driver. Those who couldn’t afford it had to fend for themselves and, as Whitlam pointed out, the fear of debt deterred people from seeking medical attention. For Whitlam, education and poverty were inextricably linked. Free education vastly improved the life chances of those who were previously denied and promised escape for those born into poverty.

Inadequate support and gaps in who received support were quickly addressed by the Whitlam government. Pensions and benefits were increased and coverage expanded to include previously ignored categories such as sole parents. Prior to 1972 the pension had been increased in an ad hoc manner with the biggest increases occurring prior to Federal elections. In the 1972 election campaign Whitlam promised to increase the age pension to 25 per cent of average weekly earnings – where it was in the Chifley years – and then index it.

In early 1972 the then Whitlam-led opposition agitated for a poverty inquiry and in response the government established one under the chair of Professor Ronald Henderson. On winning government in December 1972 the Whitlam government vastly increased its terms of reference to examine not only cash but other aspects of poverty and the need for new services. Parts of the report were released in 1975 and into 1976 following the dismissal. This report established the Henderson Poverty Line as a generally endorsed measure of relative poverty and one that is still used today. However, the recommendations of the report were ignored by the Fraser government.

A significant initiative was the quarterly wage indexation which was introduced in early 1975. Following the commodity price boom in the early 1970s inflation increased dramatically. Workers were seeking higher wages to compensate for higher prices and seeking an allowance for price increases into the future. Wage increases were no good if they were going to be quickly eroded by inflation. The Whitlam government introduced quarterly wage indexation so that workers were no longer forced to strike to be compensated for inflation. As it happened Australia’s inflation then moderated after the oil shocks and came out of the inflationary spiral better than most other OECD countries.

Whitlam also reopened the ACTU’s application for equal pay in Federal awards, a case that was won. A number of similar cases reinforced the equal pay principle, extending it to the minimum wage in 1974. Women were subsequently appointed as judges, senior public servants, and the Labor Party preselected women for winnable seats. Investigations were initiated into sex discrimination in employment, education, social welfare and the law. There was a good deal still left undone with the dismissal, and there still is! But in this area as in many others, the Whitlam government at least got important agendas moving.

40 years on and Whitlam’s vision is under threat. The recent budget called for cuts to health and education, cuts to welfare payments and increases in university fees to name a few. Inequality in Australia is increasing and the recent budget will make it worse, placing the majority of the cuts upon the poor while leaving the wealthy relatively unscathed. Tackling inequality is not an economic problem, it is a political choice.

Footnote: This relies heavily on Whitlam G (1985) The Whitlam Government 1972-75 and verified where possible against other sources.

We all lose from Medibank privatisation

The government is intending to privatise Medibank Private saying there is no reason for the government to be involved in the private health market. However, moving towards a private market in health and health insurance makes no sense. Markets and privatisations are not appropriate in health generally. Private unregulated insurance can only work, if at all, if the insured events are genuinely random. Ill health does not work like this.

The Whitlam government brought in Medibank and Medibank Private in the early 1970s: Medibank was the universal health insurance system and Medibank Private was for those who wanted private health insurance from a government-owned organisation. Medibank itself was changed and degraded so thoroughly by the Fraser government that they changed its name to Medicare.

Medibank Private remained, fulfilling its original objective of providing a government-owned alternative for people who wanted more insurance than was available under the universal scheme. As a government-owned organisation it kept the competition honest, just like the Commonwealth Bank did before it was sold. Since the Commonwealth was sold profits of the big four banks increased from two to three per cent of GDP. Medibank Private has 30 per cent of the private health insurance market and is truly a dominant player. After the sale, private health insurers will still be subject to price and quality regulation but Medibank Private will no longer be in the market as an honest broker.

The sale price of Medibank Private is expected to raise $4,269 – $5,508 million. At best this suggests the government could use the sale to pay off government debt worth $5,508 million. At present interest rates this means the government could save itself interest outlays of $183 million per annum. However, pre-tax profit of Medibank Private is expected to be $362.9 million in 2014-15. In one year after the sale the government’s revenue will be around $180 million lower than if it did not sell Medibank Private.

While the rest of the financial world is looking for deals where it can earn more in returns than it costs in interest the government is doing the exact opposite. From a commercial sense it makes no sense to sell something that is generating a net income.

So why is the government selling Medibank Private? Some like to argue that enterprises are more efficient in private hands. The press have made the point that in government ownership Medibank Private has lower profitability than the rest of the industry. The prospectus shows Medibank Private tends to be less profitable than the privately owned insurers but more than the not-for-profits. Evidently Medibank Private has pitched its pricing to achieve profitability somewhere between the for-profit organisations and the not-for-profits.

Overall it is very hard to make the case that a privatised Medibank Private would be any more efficient than a publically owned Medibank Private. One important observation can be made; Medibank Private allocated 86 per cent of its premiums to meet claims. In general insurance that figure is more like 50 per cent.

Without a government owned player in the system the government will have much less ability to scrutinise the industry and prevent abuse of the reinsurance and other arrangements.

Coal not the solution to energy poverty

In the lead-up to the G20, government, lobbyists and mining industry heads have coalesced around a single concern: energy poverty. Treasurer Joe Hockey told the BBC that Australia’s coal was a means for nations to “lift their people out of poverty.” The Prime Minister believes, rather than being an economic concern, we must export coal as it is “good for humanity”. Environment Minister Greg Hunt suggested that failing to export coal out of Queensland would be akin to “condemning people to poverty.”

There are about 300 million people in India without access to electricity. The human costs of this are tremendous. The UN has identified access to electricity as an essential component of its Millenium Development Goals.

If coal is the only way to achieve it, isn’t that all there is to it?

It isn’t. In fact, coal might be the worst of all possible solutions.

On Wednesday, Mr. Debi Goenka, from India’s Conservation Action Trust, visited Canberra for meetings with journalists and politicians. He’d heard coal being paraded as the saviour of India’s poor. He wanted to correct the record.

Coal in India contributes to more than 100,000 premature deaths annually. Nearly a third of Canberra’s population, every year, are dying from coal in a country that we’re told isn’t using enough of it.

Adani’s Carmichael coal mine, the gargantuan project in Queensland’s Galilee Basin, wants to ship upwards of 60 million tonnes of coal a year back to India. Environmentalists are concerned of the potential impact this increase in shipping traffic could have on the Great Barrier Reef. Mr. Goenka says, having seen Adani’s environmental credentials in India first hand, there’s every reason to be worried.

That coal could lift India’s rural poor into prosperity is laughable, he says. Some of the communities living around coal power plants in India have had their incomes drop by up to 80 per cent, as the country’s woeful environmental regulations have allowed pollution and degradation to decimate fish stocks.

Electricity generated from coal, he says, is not affordable to the poor, regardless of how accessible it is. Biomass fuels are used instead, as the materials are free, even if they are inefficient. “More than 300m Indians simply cannot afford Australian coal”, Goenka says.

The energy poor are really just poor, and the impacts of climate change on India, to say nothing of the pollution, will only exacerbate the problem. This side of the ledger cannot be ignored, even if it is more convenient to do so.

You can hear Mr Goenka talk about why coal doesn’t solve poverty on RN radio here.

The Australia Institute will be releasing a paper on energy poverty soon so keep an eye out for that.

TAI in the media

Liberals’ core conundrum laid bare by ANU row

Poorest families hit the hardest

Coal generates just 1.2% of Qld jobs – not 13%

NSW farmers reject land clearing report

Infographic

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Have your say in the EPBC Act review of salmon farming in Macquarie Harbour

The Australia Institute Tasmania’s work was critical to triggering the federal EPBC review of salmon farming in Macquarie Harbour.

Why maintaining ambition for 1.5°C is critical | Bill Hare

One of the key things about this whole problem is that the only way to solve it is that we need to rapidly reduce and phase out fossil fuels. That can’t wait a decade. We need to be making substantial reductions this decade.

2024 is Election Year

While we could be forgiven for thinking 2024 will be all about American democracy, this year is in fact a big one for democracies across the world, writes Dr Emma Shortis.