Corruption thrives in the dark, but this week Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus KC shone a welcome light into dark places by tabling the legislation to establish the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) in Parliament. Whether the NACC will have the power to expose corruption to sunlight, or it is restricted to a dim torch beam is now in the hands of the Parliament as the legislation heads off to inquiry.

What is clear is this legislation will fill a huge gap in Australia’s integrity system. The Attorney-General is to be commended for introducing it within six months of Labor taking office. It is a big step towards restoring Australians’ trust and faith in democracy. But it is incumbent upon this Parliament, to which the public elected an integrity supermajority in both houses, to pass the most robust anti-corruption legislation possible.

Australian voters made it clear at the last federal election that they cared about integrity and were fed up with rorts and political interests being put before the public interest. The absence of a national corruption watchdog never made sense and, since 2016, Australia Institute research has shown a majority of the public supported one with real teeth and the ability to hold public hearings.

This legislation won’t magically fix all Australia’s integrity problems, but it is a huge step forward. The Australia Institute’s National Integrity Committee of former Judges did amazing work to establish the broad principles required for an effective watchdog.

The bill delivers on most of the key principles outlined by integrity experts: it gives the NACC broad jurisdiction, strong powers similar to a Royal Commission, the power to make findings of corrupt conduct, and the ability to initiate its own investigations as well as in response to information from whistleblowers.

It will have the power to hold public hearings when in the ‘public interest’, but, in what’s suspected to be a last minute amendment agreed with Peter Dutton’s opposition, public hearings will be restricted to only occurring under ‘exceptional circumstances’. It is this specific language of ‘exceptional circumstances’ which has corruption fighters and legal experts most concerned – for good reason.

What are ‘exceptional circumstances’? It is unclear. Ambiguity will only serve to keep corruption hidden from the public and tied up in court challenges.

It is clear that public hearings are crucial to the effectiveness of anti-corruption commissions. Public hearings are critical to both find and expose corruption and misconduct to the public. Without public hearings, witnesses with key information may not know that an investigation is occurring, or may not know how the information they have fits into the case. Public hearings increase public trust, act as a deterrent. In short, public hearings serve the public interest.

No less than the former Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia shares this view. The issue was raised in the High Court as part of the Royal Commission into the Builders Labourers Federation in the 1980s where Chief Justice Anthony Mason stated that an order that a commission proceed in private ‘seriously undermines the value of the inquiry’

He said: “It shrouds the proceedings with a cloak of secrecy; denying to them the public character which to my mind is an essential element in public acceptance of an inquiry of this kind and of its report. An atmosphere of secrecy readily breeds the suspicion that the inquiry is unfair or oppressive.”

Ironically, the criticism most often hurled by opponents of anti-corruption commissions is that they don’t want public hearings because they don’t want such bodies to turn into ‘star chambers’. But star chambers were historically secret proceedings and as the former Chief Justice of the High Court pointed out, secrecy breeds suspicion, not trust.

The Attorney-General has responded to criticism of this provision by saying he’s confident the legislation gives the Commissioner the discretion to hold public hearings. He pointed out that the NSW ICAC only holds public hearings about 5% of the time, but neither does NSW ICAC have an ‘exceptional circumstances’ test before it can hold them. That tells us that when Commissions have discretion they use it wisely and judiciously.

The Attorney-General is eager to assure us that he does not want to restrict the discretion or independence of the NACC. But the ‘exceptional circumstances’ clause limits the Commissioner’s discretion and sets far too high a threshold. As one former Judge I spoke to this week said ‘it means every person who wants to avoid a public hearing will be off to the High Court’.

If the Commissioner deems a public hearing in the public interest, why should any further test be necessary? It sounds like a recipe for distrust, delay and secrecy.

The legislation allows the Commissioner to consider a number of factors, including damage to people’s reputations in whether it is in the public interest to hold public hearings and this is entirely appropriate. But as legendary corruption fighter the Hon Tony Fitzgerald AC QC (former Federal Court judge and commissioner of the Fitzgerald Inquiry) has pointed out “In a truly open society, citizens are entitled to full knowledge of government affairs. Information about official conduct does not become any less important because it diminishes official reputations.”

The government has options here. It can deal with the Opposition Leader, who declared he thought the legislation as it stands ‘got the balance right’. In the short term, this has fuelled speculation of a deal between the major parties, and has created the perception that Labor and Coalition care more about protecting each other’s reputations than upholding the public interest. Or, the government can deal with the Greens and the crossbench, who deserve credit for relentlessly pursuing this issue over many years, not least the Members for Indi Helen Haines and her predecessor Cathy McGowan. In an ideal world, the Parliament would pass a strengthened bill with unanimous support

The Attorney-General seems open to negotiation and it is clear he has heard and responded to concerns from the crossbench in drafting the legislation. It would severely undermine public trust if, in its final incarnation, the Parliament established a National Anti-Corruption Commission that favours secrecy over sunlight.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

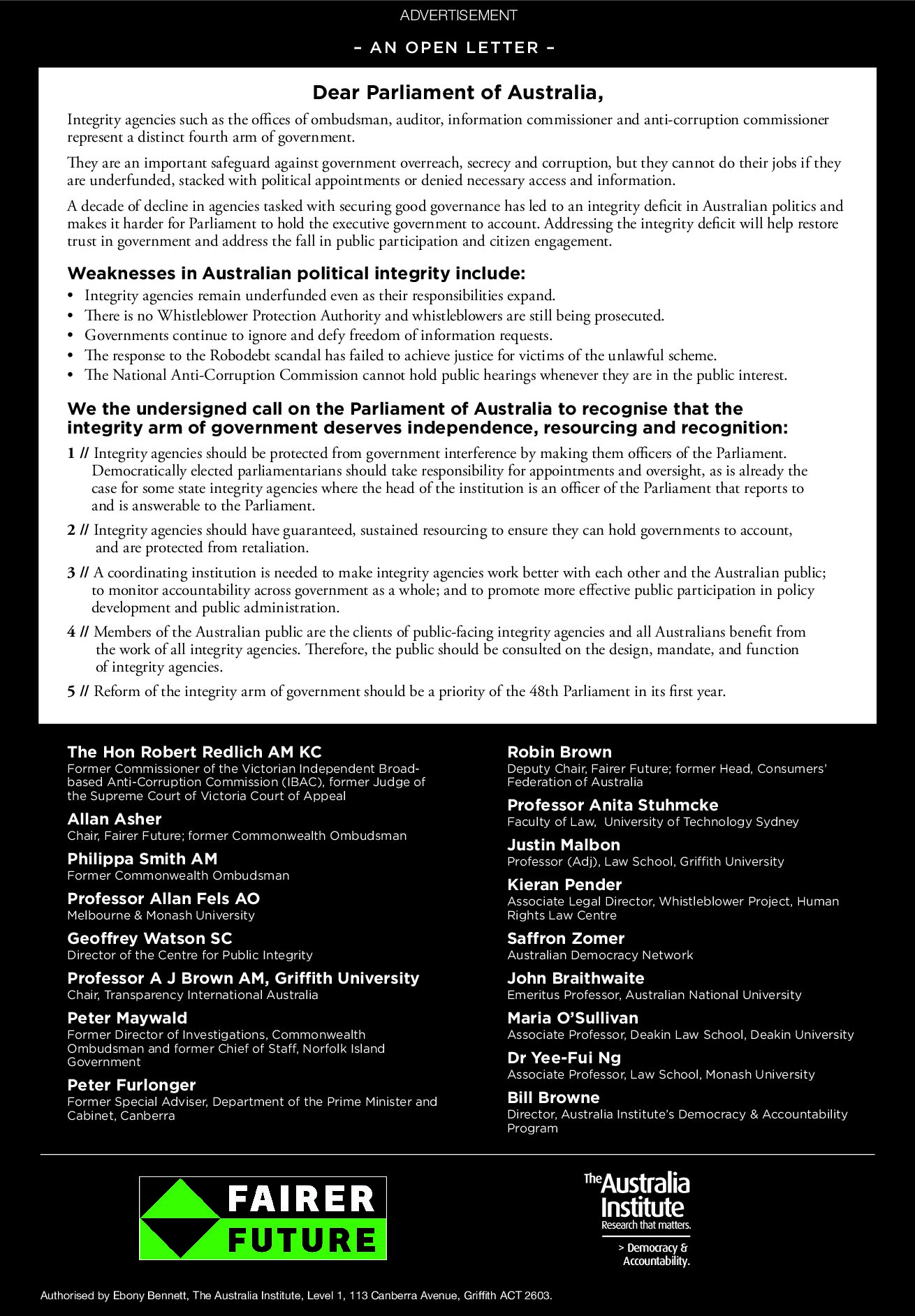

Open letter calls on newly elected Parliament to introduce Whistleblower Protection Authority, sustained funding for integrity agencies to protect from government pressure.

Integrity experts, including former judges, ombudsmen and leading academics, have signed an open letter, coordinated by The Australia Institute and Fairer Future and published today in The Canberra Times, calling on the newly elected Parliament of Australia to address weaknesses in Australian political integrity. The open letter warns that a decade of decline in agencies

Integrity 2.0 – whatever happened to the fourth arm of government?

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese came to office in 2022 promising a new era of integrity in government.

Underfunded, toothless and lacking transparency – time for a new era of integrity in Tasmania

As Tasmania’s newly elected politicians jostle to form government, new analysis from The Australia Institute shows that a deal to address integrity would be popular among election-weary voters.