by Ben Oquist

[Originally Published in the Canberra Times, 28 November 2020]

Suddenly it seems diplomacy is important. The Foreign Minister has praised the role Australia’s diplomats played in the release of Kylie Moore-Gilbert; the Prime Minister is defending the use of an Air Force plane to help get Mathias Cormann elected to the plum post of OECD Secretary-General; and the head of our diplomatic service, Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) secretary Frances Adamson, has made a rare direct intervention in the public debate as part of efforts to patch the diplomatic rift with China.

Boris Johnson recently called upon Scott Morrison to lift his game on climate ambition; John Kerry will be Joe Biden’s climate envoy and the UK’s high commissioner to Australia Vicki Treadell, is tweeting up a storm about electric cars. It is no coincidence that Scott Morrison recently floated the abandonment of dodgy offset credits to meet Australia’s Paris commitments.

It all seems a long way from last year’s effort from Morrison, where he railed against “negative globalism” in what will surely be remembered as one of the worst foreign policy speeches by an Australian Prime Minister. Morrison criticised “unaccountable internationalist bureaucracy” for demanding “conformity rather than independent cooperation”. He even paraphrased former Prime Minister John Howard, to say “we will decide our interests and the circumstances in which we seek to pursue them”.

The Australia Institute has tried to get to the bottom of why a Prime Minister would bypass the experts in DFAT. A freedom of information request was submitted to DFAT for material on the Prime Minister’s Lowy speech. Their deadline expired in September, and an extension was given. The department requested a second extension, which was declined by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. Despite the second extension being rejected, DFAT has still not provided the documents.

We do know from Senate Estimates that DFAT was not consulted on this famous speech nor a speech delivered to the United Nations the month before, where the Prime Minister controversially invented a whole new diplomatic concept when he argued that China was not a developing country. Based on Senate estimates evidence, The Australian reported that “Scott Morrison has centralised the making of key foreign policy decisions within his office”.

Before making unprecedented, sweeping statements about foreign policy and international relations, you might imagine that the Prime Minister would have consulted the experienced diplomats and analysts in DFAT. That is, after all, what the public service is there for.

This is not a time for freewheeling, ill-considered foreign policy pronouncements. The rise of China, its newfound assertiveness, its ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomacy and its newly discovered penchant for imposing trade penalties on what it sees as Australian recalcitrance has dramatically accelerated the need to do diplomacy better.

China’s contemporary diplomacy is ham-fisted. But Australia’s diplomatic efforts can also be clumsy. The Prime Minister’s United Nations speech; the poorly executed push for an inquiry into China’s handling of the pandemic; and an overreliance on slogans like “we’re not going to be lectured to”, do not a good foreign policy make.

Nor does offending our neighbours. Despite talks of a ‘pacific step up’ the Government’s love of coal, and the outright contempt it has at times shown toward pacific island states’ climate concerns, has done nothing to help secure our strategic backyard.

The new reality, whether Australia likes it or not, is that the US has managed to forfeit its global authority, while China is determined to acquire its own. Strident chest-thumping may suit the alpha-male silverbacks, but it does not work for middle-ranking powers such as Australia.

Morrison’s war on multilateral bureaucracy might have played well in the conservative media when Trump was President, but it will harm Australia’s standing and advocacy in those very forums in the term of Joe Biden and beyond.

Australia now needs a radical re-calibration of its national diplomacy.

To this end, The Australia Institute is convening a ‘conversation’ roundtable next week, to develop constructive and imaginative ways of re-engineering Australia’s diplomacy.

We need to spark a conversation about how a culture of foreign policy captain’s calls has emerged and what to do about it. Would the Prime Minister even consider announcing a major new economic policy concept without consulting Treasury? Or adopting a new legal approach without advice from the Attorney-General’s Department? Yet foreign policy is arguably even more in need of the nuance that comes from specialist foreign international knowledge.

None of this is the fault of DFAT itself. It is a wider cultural, financial and political problem. Until the community and its politicians change their attitudes to diplomats and diplomacy, things will not change.

Our round table will discuss the notion that DFAT needs substantial reinvestment—not just at the margins with a new small post here or there—but system wide. For over two decades, Australia’s diplomatic capabilities have been eroded. DFAT’s operating budget has been flat lining, marking a continuing decline in resources in real terms. Asialink research published last year reveals Australia’s spending on foreign affairs, including trade and aid, has fallen to just 1.3% of the federal budget—from 9% after World War II, and 1.9% in 1989.

While Australia spends many billions preparing for the unlikely event of war, we spend a vastly smaller amount on preventing war in the first place.

Of DFAT’s approximately 4000 Australian staff, less than a quarter are based overseas. As the world’s 13th largest economy, Australia is seriously under-represented on the world stage. As Foreign Affairs has reported, Greece, Portugal and Chile all have more foreign posts than Australia even though their populations are smaller and their GDP is less than 20% of Australia’s.

But it is not just our diplomats that need better resourcing and status, Australia’s public diplomacy is underdone. Applications of soft power abroad—teachers, artists, researchers, young people, cultural events, trade shows, visits of opinion leaders—all cultivate long-term relationships, dialogue and understanding.

But instead of strengthening Australia’s public broadcasting overseas, the ABC budget has been cut and Radio Australia shortwave broadcasting in the Pacific has been wound back—with Chinese state-owned media taking over some of the ABC’s former frequencies.

Other nations practise a wider, deeper and more engaged public diplomacy. China runs a massive global public diplomacy campaign. France, Italy, Germany and the UK fund extensive cultural and language programs. Of course, not all of it is good. While we should decry the online misinformation by countries like Russia, Iran and China, we should at the same time develop our own approach to promoting Australia’s democratic values. In a competitive world where the very idea of democracy is under attack, there is no place for complacency.

A scrooge-like approach to spending on diplomacy and foreign affairs is the last thing Australia needs. It is not in our national interest, democracy’s or the planet’s. However, to revamp Australia’s diplomatic architecture will require more than money, a shift in the cultural and political status we accord diplomacy is needed too.

Ben Oquist is executive director of the Australia Institute, an independent think-tank based in Canberra @BenOquist

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

‘Back on track’? Why that’s the wrong question on Israel

“Prime Minister, how do you get the relationship with Israel back on track from here?”

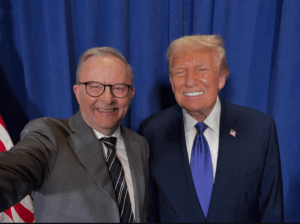

Can Albanese claim ‘success’ with Trump? Beyond the banter, the vague commitments should be viewed with scepticism

By all the usual diplomatic measures, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s meeting with US President Donald Trump was a great success. “Success” in a meeting with Trump is to avoid the ritual humiliation the president sometimes likes to inflict on his interlocutors. In that sense, Albanese and his team pulled off an impressive diplomatic feat. While there was one awkward

The 2025 federal election is the first where a major party received fewer votes than independents and minor parties.

While the May election result was remarkable for the low vote share going to the major parties, it was just the most recent of a very long trend.