Budget Blues Continue

1. Uncle Sam’s crazy education deals

When Education Minister Christopher Pyne’s vision for a deregulated tertiary education system was outlined in the 2014-15 Budget, its details weren’t a surprise.

A month earlier, Pyne made a speech to the Policy Exchange think-tank in London where he proclaimed the virtues of the USA’s tertiary education model. He heaped praise on the “competitive nature” of its offerings, declaring we have “much to learn” from its free-market fundamentals.

We hadn’t heard of this academic utopia the Minister was referring to, so we did some research. Here’s what we found.

The cost of education in the USA is skyrocketing. Tuition costs have expanded at a rate three times higher than inflation, every year. Between 2001 and 2011, the cost of a degree rose 70 per cent. It’s rising faster now.

Student debt surpassed $1 trillion US dollars in 2011. That figure’s growing at around 10 per cent a year, compared with 1.6 per cent for non-student debt levels. At this rate, US students will owe more than Australia’s total GDP by 2020.

But these figures don’t really tell the full story. There’s a human cost to this free-marketeering that doesn’t show up in the aggregate.

Consider this hypothetical American scenario: two students get the same score on the SAT exam. The first comes from a family in the top-income quartile, the second comes from the bottom quartile. The first student is four times more likely to graduate with a degree than the second, poorer student.

Why? It’s not about capability. Both students are just as gifted, after all, just as motivated as each other, and just as determined to succeed. Why is this story being played out across America?

Undergraduate dropout rates are higher in the United States than anywhere in the world, except for Hungary. The number one reason given for dropping out? Financial strain.

The Abbott government insists the deregulation agenda will finally free higher education institutions to become “Australia’s Harvard”. Nearly half of Harvard’s undergraduates come from the USA’s wealthiest 4 per cent of families.

In February of this year, US Secretary of Education Arne Duncan acknowledged a looming crisis in higher education. He said it was “deeply troubling” that academically-able high school graduates aren’t enrolling in further education anymore, because they “simply can’t afford it.”

If Australia wants to pick a model to emulate, why would it choose the one where the richest 25 per cent get more diplomas than the bottom 75 per cent combined?

Deregulation means higher education for the highest bigger. It’s a recipe for social inequality, and it’s a recipe Australia needn’t follow.

2. Mining for good government

What is the role of government? This is one of the fundamental questions in politics, economics and philosophy. A question that has been debated over thousands of years and on millions of parchments, pages and stone tablets. Confucius, Plato, Marx – they’ve all had a go.

This week our Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, made his contribution to this eternal debate:

Our job in Government is to keep mining strong.

It’s a genuinely original answer and one which provides insight into the recent Budget decisions to reduce taxes on mining and increase taxes and payments on just about everyone else. The Prime Minister expanded in his speech to the Minerals Council of Australia:

[Our job is] not to tell you [miners] how to do your job; it is to allow you to do your job.

The job of mining companies is the subject of far less debate. Most thinkers agree it is to dig stuff up and maximise profits. One of the things they dig up, of course, is coal. On coal, the Prime Minister went into specifics:

It’s particularly important that we do not demonise the coal industry and if there was one fundamental problem, above all else, with the carbon tax was that it said to our people, it said to the wider world, that a commodity which in many years is our biggest single export, somehow should be left in the ground and not sold. Well really and truly, I can think of few things more damaging to our future.

He’s right on his first point. We shouldn’t demonise the coal industry, we shouldn’t pander to it either.

At TAI we can’t think of anything less damaging to Australia’s future than making the coal industry better regulated and cleaner. The carbon tax forms part of this approach. The policy influences the cost of coal production by requiring mining corporations to incorporate the cost of coal use has on the environment. A cost that will increase into the future as the need to address climate change increases.

Maybe our lack of imagination is what keeps us off the list of great thinkers – Confucius, Plato, Marx, Abbott…

3. Life expectancy and the age pension

The current government wants to increase the age at which Australians become eligible for the age pension. They argue that the longer life expectancy for people today, compared to when the pension started, means that people should be working longer and receiving their pension even later in life. The pension age of 65 years was set when it was introduced soon after Federation, when life expectancy was 55. Treasurer Joe Hockey has made the point that the pension eligibility age should increase in line with life expectancy, rather than stay where it was over a hundred years ago.

In response to similar arguments in The Economist, staff from the World Health Organisation wrote in to point out that such policies ‘have their greatest impact on the poorest and least healthy’ and that ‘generic approaches to pensions based on chronological age can simply reinforce the cumulative impact of inequities experienced across a lifetime’.

Moreover, the arguments based on life expectancies are incorrect, ‘since life expectancy largely reflects survival at younger ages, not health or capacity to contribute in older age’. When infant mortality was so much higher the average life expectancy did look a lot lower; but those low life expectancy figures don’t tell us much about how long people might be expected to live having attained adulthood. That was clearly the more important consideration for Australia’s first government in planning our retirement system.

In the lead up to Federation the population had been growing rapidly at almost 5 per cent per annum between 1833 and 1901. In a population growing so rapidly there are relatively few people aged 65 or over, and in 1901 they were just 4.0 per cent of the population.

Of course when the age pension was introduced those 65 and above were not the only ones that needed to be looked after. Society also had to look after the young ones. In 1901 the number of people below 15 years of age was 35 per cent of the population. Hence in 1901, 39 per cent of the population were not of working age.

Population figures from June 2013 show that the population of those aged 65 and over has increased and now stands at 14 per cent. But the number of young people has fallen from 35 per cent at the turn of the twentieth century, to just 19 per cent in 2013. So whilst we have more older people, we have far fewer younger people to look after.

This means that in 1901, 39 per cent of the population were not of working age, but now only 33 per cent are not of working age.

While these figures show that Australia’s demography is much more favourable than it was in 1901 in terms of providing support to those who need it, all that is overwhelmed by one other major factor.

Using ABS estimates and the Reserve Bank conversion factor, Australia’s real income per head is over 10 times what it was in 1901. And what that means, is that if we could afford to provide a pension to those aged 65 and over then, we can easily afford to do it now. You can read our report into a universal age pension here.

4. Youth unemployment

In the 2014 Budget, the Abbott government announced that unemployed under 30s will now have to wait six months before receiving any kind of income support.

This move was widely condemned as a punitive measure that will place undue stress on those already struggling. Following a Budget in which we are all meant to do some ‘heavy lifting’, it’s worth looking at this decision in particular, and the causes and impacts of youth unemployment.

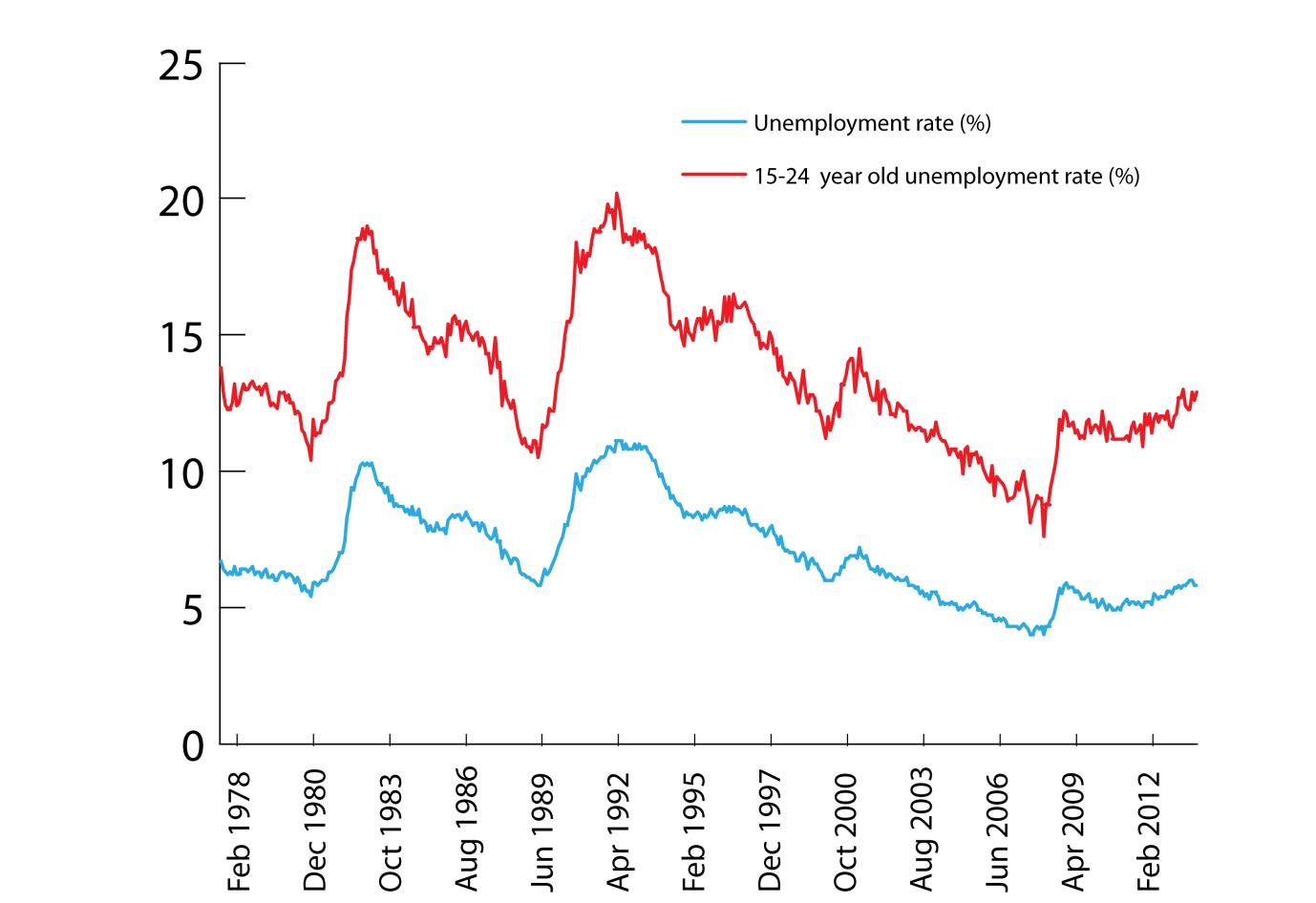

The latest unemployment figures from the ABS show that in April there were 713,400 unemployed people in Australia – an unemployment rate of 5.8 per cent. The unemployment rate for young people aged 15-24 years was more than twice as high at 12.9 per cent (266,000).

The unemployment rate among younger Australians is consistently higher than the unemployment rate for the population as a whole. Figure 1 shows historical rates for total and youth unemployment.

Figure 1: Total unemployment and youth unemployment rate (%)

Source: ABS (2014) Catalogue No. 6202.0.

The ABS data also shows that the average length of time young people remain unemployed has been getting longer.

Young people experience higher levels of unemployment than the working age population overall, for a variety of reasons including their relative lack of experience and the time it takes for people entering the workforce to find a suitable position, apply, interview and start work. These factors are compounded by broader issues of variations in employment opportunities across industries and different parts of the country, both urban and regional.

Despite these barriers to employment, the Treasurer expects young people to have a job. Effectively he expects zero per cent unemployment, despite the fact that economists all agree there can never be zero unemployment due to the reasons above, and a host of others not specific to young people. Economists call unemployment as a result of these barriers “frictional unemployment”.

We will most likely remain with an unemployment rate higher than that of the ‘frictional’ rate due to the macroeconomic policy of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). This policy is focused on keeping the inflation rate at between two and three per cent, rather than keeping unemployment at a certain level.

While it is a widely accepted notion that some unemployment is necessary to prevent inflation, the historically higher youth unemployment rate means younger people shoulder more of the resultant burden.

At the same time as cutting all benefits available to young people who find themselves out of work, the Budget papers actually predict that unemployment will rise from 5.6 per cent in 2012-13 to 6.25 per cent in 2015-16.

The question still remains as to why this group have been considered less deserving of income support, even as it is accepted that their numbers will continue to grow.

5. TAI in the media

Australians unaware of emissions investment: Aust Institute Millions of Australians are unwittingly investing in new coal and gas projects which are driving climate change, according to a report produced by The Australia Institute and launched in conjunction with 350.org and Market Forces.

Eating lunch away from your desk could be the best thing you do for your health today

“Who has a lunch hour anymore?” lamented a friend recently, confessing she regularly wolfs down a sandwich while sitting in front of her computer. …Aussies routinely don t break for lunch. The AIs executive director, Dr Richard Denniss says the long lunch is a thing of the past but forgoing it…

Tony Abbott’s Budget, tax strategy lacks conviction and logic

If Joe Hockey was actually determined to broaden the base of the GST he wouldn’t start by including food, he would start by imposing it on private school fees and private health insurance. Not only would he collect billions in revenue, he would raise it primarily from high-income earners. While the poorest Australians spend a relatively large share of their Budget on food they rarely send their kids to expensive private schools.

You can hear Richard speaking at the ‘Defend World Heritage’ meeting in Hobart here

Our researchers were the stars of our last Politics in the Pub, speaking about the Commission of Audit and the Budget.

You can watch them here, along with all our other Politics in the Pub events.

6. Infographic

7. Weekly Updates from TAI

We aim to keep you updated every week. Every fortnight we send out the Between The Lines, which you’re reading now, which provides an overview of our research and topical issues. On alternate weeks we send out a newsletter based on our work in equity and mining. If you would like to receive those, click here, choose your newsletter, and we’ll make sure they land in your inbox.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Harmless budget of missed opportunities

This pre-election budget is designed to annoy as few people as possible.

Taxes on tampons, tax breaks for luxury utes: gender in the budget

Last week, the federal government announced plans to define menstrual products as “lifestyle-related” and exclude them from NDIS funding.

What to expect on Election Day: history could be made, or we’re in for a long wait

As Americans vote in one of the most important presidential elections in generations, the country teeters on a knife edge. In the battleground states that will likely decide the result, the polling margins between Democrat Kamala Harris and Republican Donald Trump are razor thin.