Chalmers is right, the RBA has smashed the economy

In recent weeks the Treasurer Jim Chalmers has been criticised by the opposition and some conservative economists for pointing out that the 13 interest rate increases have slowed Australia’s economy. But the data shows he is right.

Last year the government announced it was considering removing its statutory power to overrule the Reserve Bank. Thankfully it has now reconsidered that move, and the actions of the RBA over the past year serve to remind everyone that it is far from infallible.

In its May Statement on Monetary Policy the RBA looked ahead one month and estimated that in June the annual growth of household consumption would be 1.1%. When the national accounts were released last week, the actual growth was revealed to be just 0.5%.

Now obviously economic forecasting is a bit of a mugs game, but household consumption makes up half of Australia’s economy and accounted for around 45% of all the growth in the economy over the past decade so it is pretty important. It is also the area of the economy most directly affected by interest rate rises. This error of forecasting suggests that the Reserve Bank has rather poorly misread just how greatly households had been impacted by the 13 rate rises that had taken the cash rate from 0.1% in April 2022 to 4.35% in November 2023.

This error is crucial because the main reason the RBA raises rates is to reduce the ability of households to spend. Because you can’t tell your bank that you don’t really feel like paying your mortgage this month, interest rate rises force households to divert money that would have been spent on goods and services to paying your mortgage.

The problem is when you are trying to slow down half of the economy so directly, if you overdo it the entire economy begins to fall. This is what happened in the early 1980s and 1990s when interest rates were raised sharply in order to slow inflation.

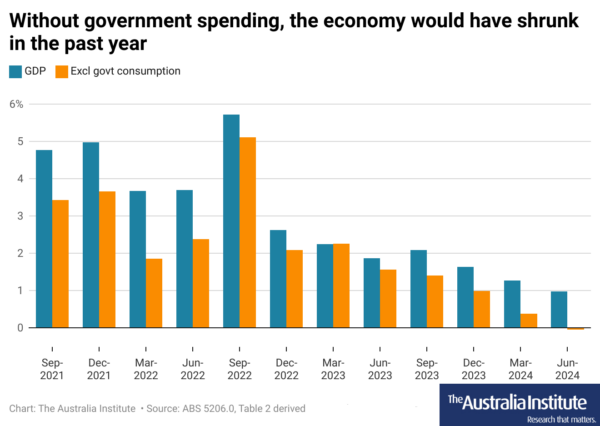

And the private sector has already slowed so greatly that the only reason GDP rose in the past year was because of increased government spending.

That is not a sign of a strong economy, nor a sign of one, according to the assistant governor of the RBA, Dr Sarah Hunter, that “is running a little bit hotter than we thought previously”.

Economies that are running a bit hot are ones in which households are spending a lot more than they were the year before because unemployment is falling and wages are rising well ahead of inflation. Instead we currently have a situation where unemployment has risen from 3.5% in June last year to the current level of 4.2%, household spending grew just 0.5% – well below the long-term average of 3% – and real wages in the past year rose just 0.1%.

When asked about this discrepancy between reality and the RBA’s belief, the Governor of the Reserve Bank, Michele Bullock told reporters last week that

…it’s the difference between growth rates and levels.

She noted that “it’s true that the growth rate of GDP has slowed” but that “part of monetary policy’s job has been to try and slow the growth of the economy because the level of demand for goods and services in the economy is higher than the ability of the economy to supply those goods and services. So there’s still a gap there. So even though it’s slowing, we still have this gap.”

In effect Bullock was telling people to stop worrying about the fact that household consumption was barely growing or that GDP only grew because of government spending or that GDP per capita has fallen for a record 6 consecutive quarters because the amount of consumption and GDP was too high.

This could make sense – think of it like a car travelling on a 60km/h road. If it was travelling at 80km/h and slowed to 70km/h even though it was slowing it would still be going too fast.

In essence this is what Bullock is arguing is happening to demand in the economy – it is slowing but overall there’s still too much of it.

The only problem is that this is completely wrong.

Consider the suggestion that the demand for goods and services is higher than the ability of the economy to supply those goods and services. One simple way to look at this is to see if the amount of goods and services bought per person is currently at a level consistent with the growth observed in the decade before the pandemic.

This is actually not a major test – household consumption, along with most of the economy was rather weak in the 7 or 8 years before 2020. The RBA at the time actually was hoping Australians would spend more than they did, so you would expect in an economy with too much demand that the amount of things we are buying is well above the levels of that particularly weak period.

But it is not.

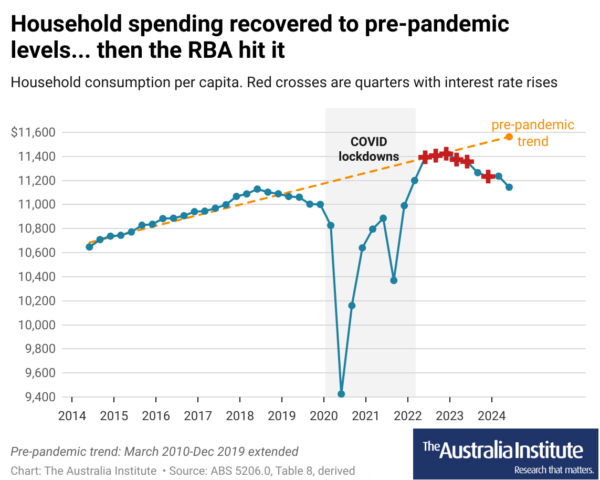

As we can see from the below graph, while household spending did quickly recover after the lockdowns in 2020 and 2021, by the time the RBA began raising interest rates our level of demand for goods and services was only back to the level consistent with the pre-pandemic growth.

Now yes you can argue the RBA was right to increase rates at that time – to ensure our spending didn’t keep zooming up in recovery. But by the time of the 10th rate increase in March 2023, household spending per person was already falling and 0.7% below the pre-pandemic trend. When the RBA raised rates for there 12th time in June 2023, the level of demand for goods and services was 1% below the pre-pandemic trend.

At this point you might think the RBA had done enough. But after pausing for 4 months, the bank inexplicably raised rates for a 13th time in November 2023. At this stage household level of spending was 2.5% below the pre-pandemic trend.

And because interest rate rises take months to worth through the economy we now find ourselves at a point where the level of household consumption per person is 3.8% lower than would have been expected had households merely kept increasing our consumption in line with the decade before the pandemic.

In effect Australians are currently consuming almost the same amount of goods and services as they did in June 2018 and yet the head of the RBA would have us believe that is a case of excess demand.

If we look at the overall economy, the picture is much the same (see the graph at the top of the page). Australia’s level of GDP per capita did recover quickly after the lockdowns and by June 2022 was 1.4% above the pre-pandemic trend level. But the interest rates rises had an immediate impact – reducing GDP per capita in 7 of the next 8 quarters. By June 2023 the level of activity in the economy was already below pre-pandemic expectations, and when the RBA hit Australians with the 13th rate rise in November 2023, the level of GDP per capita was 1.2% below the long-term trend.

It is now 2.5% below – back at the level it was in June 2021.

The RBA has got it wrong. They were initially worried that inflation was driven by concerns of strong wage growth rather than supply side issues and corporate profits. They then tried to argue household spending was still growing too strongly. The GDP figures showed that to be woefully mistaken. They then tried to argue that while growth in the economy was slow, there was still too much demand. But again the figures show this to be mistaken.

The Treasurer Jim Chalmers stated nothing but the facts when he said earlier this month that rate rises were “smashing the economy”. The data supports his assertion, and it is time the RBA admits that their actions have not only slowed the economy but slowed it at a pace that is now harming Australians for no benefit other than the RBA saving face from its previous over-reactions.

Related research

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

When targeting inflation, the RBA misses more often than it hits

With the fight against high inflation now over, will the Reserve Bank fail to learn the lessons of the past and allow inflation to fall below 2%?

If business groups had their way, workers on the minimum wage would now be $160 a week worse off

Had the Fair Work Commission taken the advice of business groups, Australia lowest paid would now earn $160 less a week.

Fearful and frozen: Why the Reserve Bank continues to err on rates

The RBA’s failures have real consequences. It should go back and closely reread the recommendations of the RBA review, particularly the ones that encourage it to open up to new and diverse viewpoints.