Share

Was it really the Treasury’s economic modeling that convinced Prime Minister Turnbull to abandon his plan to raise the GST and cut income taxes? Treasury simulations indicated the trade-off would have no significant impact on growth. Or perhaps it was another kind of calculation – electoral – that convinced the Coalition to drop the idea, and the economic numbers just provided political cover.

Whatever the motive, the constituency most disappointed by this about-face is the corporate sector. Business leaders hoped to ride the coat-tails of a “tax shift” to achieve a significant reduction in company income taxes. And they continue to beat the drum for lower business taxes, financed if necessary from other fiscal savings. By sweetening after-tax returns, they argue, business capital spending will accelerate: driving GDP expansion, more jobs, and fiscal dividends for government. In short, everybody wins.

But is their promise of a growth dividend realistic?

Never mind economic models, which depend entirely on whatever assumptions are programmed in by the modelers. Instead, let’s consider some real-world experience to judge whether company tax cuts would indeed generate a significant growth dividend. Canada’s recent experience with deep corporate income tax cuts is especially relevant to Australia, given the structural similarities between the two economies: large geography, dependence on major resource projects, and large inflows of foreign capital.

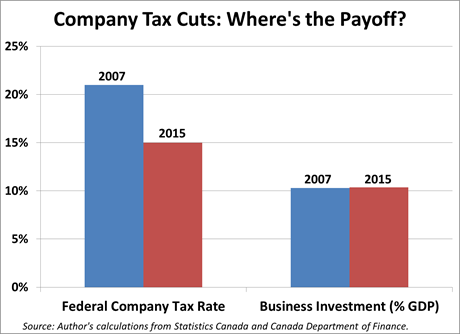

The Canadian federal government implemented three successive federal corporate tax reductions over the last generation. (Provincial governments also levy their own corporate taxes, averaging around 10 per cent, added to federal levies.) The first stage occurred in the late 1980s: the statutory rate was reduced from 36 per cent to 28 per cent, but various loopholes and deductions were closed in the process. The second reform occurred early this century: the general rate fell to 21 per cent, and preferences for manufacturing and resources were eliminated. The latest cuts were implemented beginning in 2007 by former Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper (defeated in last year’s election): he cut the base rate to 15 per cent, and eliminated a 1.1 per cent CIT surtax. Those last reductions alone still cost the federal government over $15 billion (Canadian Dollars) in foregone revenue each year.

Together, these successive cuts reduced combined Canadian corporate taxes (including provincial rates, which also fell in several provinces) from near 50 per cent of pre-tax income in the early 1980s, to 26 per cent today. In theory, the resulting boost to profits should have stimulated a strong response in business investment. Unfortunately, hopes for this “jobs and growth” dividend have been repeatedly dashed.

Instead of growing, business spending on fixed capital (machinery, structures, etc.) declined under lower company taxes, by about one full point of GDP since the reforms began. Business innovation spending (one of Mr. Turnbull’s top priorities) fared even worse: business R&D outlays shrank by over one-third as a share of GDP, to a record low of just 0.8 per cent. In fact, over the last decade real business investment performed worse than during any other era in Canada’s postwar history. Several provincial governments have given up waiting for the promised investment boom, and are now increasing company tax rates to help address chronic deficits.

It is instructive to compare Canada and Australia’s investment performance over this period. Both countries face the same booms and busts in global commodity prices. Yet in the last decade business spending on fixed assets grew more than twice as fast in Australia, according to OECD data: by 3.9 per cent per year in Australia (after inflation), despite higher company taxes, versus an anemic 1.7 percent in Canada. Canada’s GDP outgrew Australia’s in just two of those ten years, and last year the country slipped into outright recession.

One especially painful side-effect of lower company taxes has been the sustained accumulation of liquid assets by Canada’s non-financial businesses. Corporate cash hoarding accelerated dramatically after the turn of the century. Non-financial firms now hold cash and other liquid assets equal to over 30 per cent of GDP. IMF researchers have shown that corporate cash holdings grew faster in Canada than any other G7 economy (and twice as fast as in Australia).

With businesses investing less than they receive in after-tax cash flow, lower taxes only add to the stockpile of idle liquid assets, draining spending power from the economy. In this regard, lower corporate taxes may very well have weakened growth and job-creation, not strengthened it. In any event, Canada’s experience is a sobering reminder to Australian policy-makers: anyone expecting a tax shift to generate a big growth dividend is likely to face chronic disappointment.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

10 reasons why Australia does not need company tax cuts

1/ Giving business billions of dollars in tax cuts means starving schools, hospitals and other services. Giving business billions of dollars in tax cuts means billions of dollars less for services like schools and hospitals. If Australia cut company tax from 30% to 25% this would give business about $20 billion in its first year,

Canada, don’t make the same mistake with LNG that Australia did

For decades, the populous eastern states of Australia had an abundant supply of low-cost gas.

Company tax cuts would do little to boost investment and hurt everyday Australians – new analysis

When Treasurer Jim Chalmers brings the nation’s economic leaders together next month, don’t be surprised if big business pushes – yet again – to cut the company tax rate.