Eight things you need to know about the Government’s plan to change Australian elections

And eight ideas to improve it

This week, the Albanese Government proposed major changes to Australian elections, including more taxpayer funding of political parties and members of Parliament, limits on political donations and caps on how much can be spent on an election campaign.

The Electoral Legislation Amendment (Electoral Reform) Bill 2024 is over 200 pages of complicated and technical changes to how democracy works in this country. It passed the House of Representatives last night – just two days after it was first made public – but it is the Senate, the house of review, that will decide whether it becomes law.

This has all happened unusually fast. Even parliamentarians and political scientists are struggling to get their heads around what would change and what it would mean for Australian democracy.

Here are eight things you need to know about the Government’s plan to change elections, and eight ideas for how to improve it.

1. There would be more public funding of incumbent parties and politicians

In Australia, parties and candidates receive about $3 per vote they receive. Everyone casts two votes – one for the House of Representatives and one for the Senate – so every election you decide how about $6 of taxpayer money is distributed.

Because parties and candidates get this money after the votes are counted, it only benefits those who are contesting the next election. A new party or candidate doesn’t get any money for their first campaign.

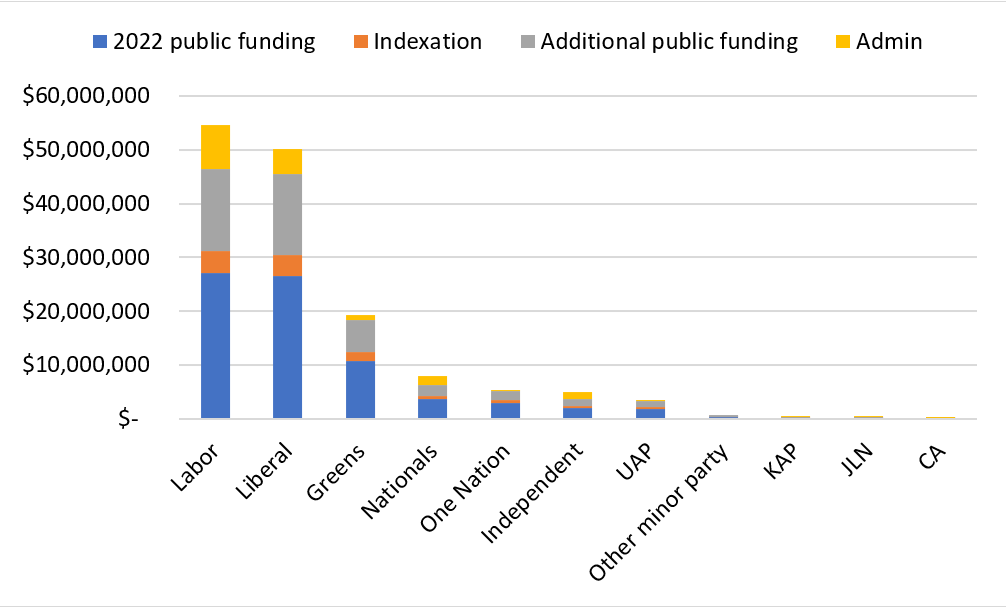

This bill would increase per-vote public funding to $5 per vote. This will cost another $41 million per three-year election cycle, with about three-quarters (75%, or $32 million) going to major parties.

How could this be improved?

By redirecting the taxpayer money we already spend on public funding to a system that new entrants can participate in too – like the democracy vouchers in use in the City of Seattle.

2. There would be new administrative funding for each MP

As well as new per-vote public funding, the bill introduces $17 million in new administrative funding: $90,000 per election cycle for a member of the House of Representatives and $45,000 per cycle for a senator.

If this funding were already in place, it would have been worth $8.1 million for Labor, $4.7 million for the Liberals, $1.6 million for the Nationals and $0.9 million for the Greens.

New parties and candidates – who also have administrative costs – get nothing.

There’s no explanation for why senators get half as much as members of the House of Representatives. The cynical theory is that it is intended to reduce funding to minor parties, who hold more seats in the Senate than in the House.

Overall, if the bill passes then Labor and Liberal will each receive about $50 million in public funding per election cycle, and about $150 million total will be spent on parties, sitting MPs and candidates. $60 million is new funding, on top of what they are already paid under existing laws.

How could this be improved?

By putting a reasonable cap on administrative funding going to a party; by funding all parliamentarians equally; and by making administrative funding accessible to new parties and candidates.

3. There would be a cap on donations to fund campaigning

Gifts to fund election campaigning are capped at $20,000 per calendar year (with the option to give before and after an election, for a total of four opportunities to give in a three-year election cycle). That’s a cap from a donor to any one candidate or party.

However, there are actually nine registered Labor parties: one for every state and territory and one federal, so there are nine opportunities to give to Labor in a given calendar year ($180,000 per year or $720,000 in an election cycle). The Liberal Party has eight parties, and the National Party five – so someone can still donate over a million dollars to the Coalition every election cycle.

This is not lost on political parties; after the Liberal party room were briefed on the changes: “One participant in the debate quipped that the Liberal National party of Queensland should split so that there would be more entities for donors to give to.”

48 hours and they already spotted a loophole.

How could this be improved?

A higher cap, like $60,000, that applies per electoral cycle would be fairer. That way, parties that have been collecting donations every year since the last election have the same overall cap as candidates and parties who get started in the months ahead of an election.

4. “Nominated entities” give the major parties a way around donation caps

The bill creates “nominated entities” where parties can park their assets, accumulated over decades, and continue to receive funding outside the gift cap.

Exactly how these entities will work is still unclear, but we know that in Victoria they are used to give large amounts of money to major parties outside of the donation caps that apply to everyone else. In fact, an independent review this year recommended that Victoria abolish nominated entities – and they are the subject of a constitutional challenge on the basis that they infringe political communication.

How could this be improved?

Scrap nominated entities. Everyone should compete on a level playing field.

5. There are spending caps with loopholes for political parties

Spending caps limit how much can be spent on an election campaign: $90 million across the whole country, and no more than $800,000 targeting each of Australia’s 150 seats.

A cap on per-seat spending may seem reasonable, but there are glaring loopholes:

- All of an independent candidate’s campaigning counts towards their $800,000 cap. But a party candidate’s campaigning only counts if it names the candidate. “Vote Labor” or “Vote Liberal” is uncapped.

- A party can count some of its advertising towards its Senate cap, even if it also names its candidate in a particular seat.

- A party can promote ministers and shadow ministers across the whole state, and not count that promotion towards the particular seat that the minister is running in.

Not to mention that a sitting member of Parliament already has millions of dollars in incumbency advantages; a challenger needs to spend more money just to catch up.

How could this be improved?

By allowing higher caps for new entrants than for sitting members of Parliament and by counting all of a party’s spending in a seat towards the cap, just like everyone else.

6. There will not be truth in political advertising laws

Even though political campaigns will be getting another $40 million or so in taxpayer funding, there will be no guarantees that this public money must be spent on accurate advertising. In Australia, it is still perfectly legal to lie in a political ad.

The Albanese Government has introduced a separate bill that would implement truth in political advertising laws, but they are neglecting it. Even though truth in political advertising laws are tried and tested (they have been in place in South Australia for almost forty years), they have been put on the backburner.

How could this be improved?

By passing truth in political advertising laws before any increase in public funding for political campaigns. The legislation is in Parliament, it just needs to be prioritised.

7. The process has been rushed and deeply flawed

The Albanese Government has had over two years to develop proposed election reforms. It received a report from the parliamentary inquiry in June last year. It has delayed the legislation multiple times because it is so complicated and potentially unconstitutional.

The changes don’t even come into effect until 2026, for the 2028 election.

But the Government want to push the legislation through in just a few days, before anyone has time to analyse it.

How could this be improved?

By holding a parliamentary inquiry into any major changes to Australian elections. That’s the Australia Institute’s position, and polling research shows four in five Australians agree – as do thousands of Australians who have signed our petition so far.

8. There are positive changes: more transparency for political donations

The bill also widens the definition of gift to include cash-for-access payments, closing a loophole. It also lowers the donation disclosure threshold to $1,000 (for gifts funding election campaigning not other party and candidate fundraising) and brings in real-time disclosure.

How could this be improved?

Spin off these non-controversial and non-complicated improvements to transparency into their own bill, and pass that alongside truth in political advertising laws.

Conclusion

Rushed legislation that would dramatically change how Australian elections work needs careful consideration, including by a multiparty committee that all Australians give feedback to.

Even a preliminary look shows loopholes and unfair treatment. Our democracy depends on getting these changes right.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

The election exposed weaknesses in Australian democracy – but the next parliament can fix them

Australia has some very strong democratic institutions – like an independent electoral commission, Saturday voting, full preferential voting and compulsory voting. These ensure that elections are free from corruption; that electorate boundaries are not based on partisan bias; and that most Australians turn out to vote. They are evidence of Australia’s proud history as an

Gender parity closer after federal election but “sufficiently assertive” Liberal women are still outnumbered two to one

Now that the dust has settled on the 2025 federal election, what does it mean for the representation of women in Australian parliaments? In short, there has been a significant improvement at the national level. When we last wrote on this topic, the Australian Senate was majority female but only 40% of House of Representatives

South Australia’s leap into the unknown with political finance changes

July 1 marked a dramatic change in how political parties and candidates are funded in South Australia.