Election entrée: Dark money and your money pay for most of the political ads you’re seeing

Share

At this stage of the election, you have no doubt seen plenty of political ads.

They’ll be on your TV screens, buffering at the start of YouTube videos and filling up your letterbox.

Who funds these ads?

Well, in large part, you do.

Over three years, Australia’s political parties received roughly a third of their money, $208 million, from the taxpayer.

And nobody knows where another third of their income came from.

Dark money

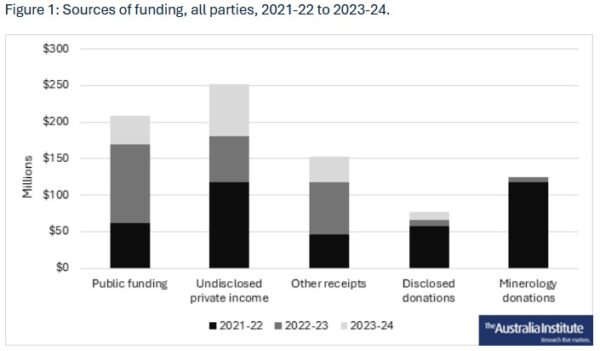

As Figure 1 shows, undisclosed funding (also called “dark money”) was the largest source of political parties’ income over the three-year period to 2023-24.

Some of that money is undisclosed because it was comprised of small donations gifted by small donors – individuals, small businesses and the like.

A party reliant on that sort of funding will inevitably record a large share of “dark money” in its finances.

But sometimes large donors find ways of evading donation disclosure rules, chiefly by splitting donations over time or spreading their contributions across multiple branches of a single party.

We don’t know what share of undisclosed donations are from bona fide small donors and what share are from large donors splitting their donations.

When the Albanese government proposed sweeping and unfair changes to Australia’s electoral laws last year, the bill’s main redeeming feature was the promise of lowering the donation disclosure threshold from nearly $17,000 (where it sits currently) to just $1,000.

But when the major parties stitched up the deal that saw the bill pass, they raised the new threshold to $5,000. This means “cash for access” payments of $4,999 and less will remain in the dark – which is seemingly most of them.

The Australia Institute, along with the Centre for Public Integrity, Australian Democracy Network and Transparency International Australia, have advocated for all cash-for-access payments to be disclosed, regardless of their size.

Over $100 million in contributions from the mining company Minerology have been placed in a separate column.

These contributions are significant, but exclusively went to Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party – so to include them in the donation figures for other politicians would distort the picture of how most candidates and parties are funded.

Public funding

Better the devil you know.

At least that was the argument for “clean” election funding when it was introduced in 1983.

Theoretically, public funding compensates parties for spending on election material such as advertising. But as Australia Institute research has pointed out, candidates only receive that money after an election campaign, leaving first-time contenders at a disadvantage.

That’s not the only problem with public election funding. At the federal level, there’s nothing stopping parties from using your money to tell you lies. South Australia and the ACT both have truth in political advertising laws, but federal MPs have not yet followed suit.

In 2024 the Albanese government drafted a bill to introduce truth in political advertising for federal elections, but they did not proceed with it. Instead, they prioritised a significant boost to public funding, which the Coalition supported. That means future elections will feature even more advertising with no disinformation guardrails attached.

There’s nothing wrong with political parties wanting to persuade voters. Political debate is a good thing and spending on political advertising is wholly legitimate.

But voters are entitled to expect certain standards from political parties that are in large part taxpayer funded.

For instance, in NSW parties are now more dependent on public funding than some public sector agencies such as art galleries and museums – but with much less public accountability.

Nobody has stopped to ask Australians what they expect in return for their money.

A bit more donations transparency and a lot more accountability for misleading advertising would significantly improve the quality of Australia’s election contests.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

More than 70% of Australians saw misleading ads during the election campaign – poll

A new poll conducted for The Australia Institute has found that 72% of voters saw misleading political advertisements during the recent election campaign, with well over half of those exposed to misleading ads every day.

The election exposed weaknesses in Australian democracy – but the next parliament can fix them

Australia has some very strong democratic institutions – like an independent electoral commission, Saturday voting, full preferential voting and compulsory voting. These ensure that elections are free from corruption; that electorate boundaries are not based on partisan bias; and that most Australians turn out to vote. They are evidence of Australia’s proud history as an

Election entrée: think three-year terms are too short? Spare a thought for generations past.

Complaints about the brevity of three-year parliamentary terms are common in Australia.