Forever Young (and forgotten)

For a cost-of-living budget, there was not much help offered for one group that is particularly affected by higher prices: young people. Young people earn some of the lowest wages, making them particularly vulnerable to the effects of inflation.

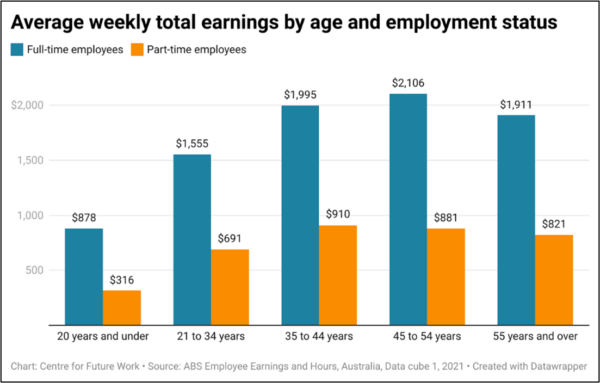

Workers aged 21 to 34 earn on average $1,207.90 per week – 29% less than those between 45 and 54 years, and 13% below the average for workers of all ages. Even accounting for the fact that young people are more likely to work in part-time and casual jobs, they still earn much less (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

Pre-budget, the Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee urged the Government to raise benefit rates in working-age income security programs, including JobSeeker and Youth Allowance. The Committee criticised existing benefit levels for being “seriously inadequate,” and subjecting the people living on them to the “highest levels of financial stress in the Australian community.” In response, the government is increasing the base rate for working-age and student payments by $40 per fortnight, as of September 2023. This raises the daily payment of JobSeeker to $52.40 and for Youth Allowance to $43, still 41% and 51% below the poverty line respectively. For context, people working full time on the minimum wage live on $116 per day. Raising these poverty-inducing benefit payments was quite rightly a top priority for a cost-of-living budget. These payment increases are clearly inadequate.

Another example of the government having the right priority, but not providing enough funds to achieve the desired result, was the increase in Commonwealth Rent Assistance. As noted above, the Government has committed to a 15% increase in the CRA, costing $2.7 billion over 5 years. That results in $23.60 extra per fortnight – raising the payment to $90.40 per week (for single people on the maximum rate). On average, for people on Youth Allowance or JobSeeker, the CRA covers around 25% of fortnightly rental costs. In 2021 around 75% of Youth Allowance recipients who receive CRA were in housing stress, meaning they spend more than 30% of income on housing costs. Young renters in particular need more support than this budget provided.

What’s more, the government recently turned down another opportunity to boost the financial prospects of young people (and other university graduates) by rejecting a bill to freeze HELP debt indexation. HELP debts are presently tied to inflation; outstanding debts will increase by an eye-watering 7.1% in June this year. On an average debt of $24,770.80, this means an increase of $1,758.70 – further delaying repayment on debts that already take 9.5 years on average to pay off.

The mounting pressure of rising educational debts and longer repayment periods has multiple consequences when young people are establishing independence. Repaying debt lowers disposable income, making it hard to weather a cost-of-living storm – but also harder to save money for a mortgage deposit. Worse still, these debts are factored in when applying for other financial loans. There are already enough financial barriers to home ownership for young people; the additional pressure of HELP debt is unnecessary.

Delivering meaningful cost of living relief for young Australians, of course, comes with a price tag. But this only highlights, once again, the enormous missed opportunity in this budget to strengthen the government’s revenue base by cancelling the Stage 3 tax cuts. Those income tax cuts will cost $21.5 billion in their first year in effect, and young people will receive only 3% of those benefits (since very few young people earn enough to qualify for those savings, targeted at higher-income taxpayers). Once again, we are reminded that budgets are about choices.