How parliaments share power | Fact Sheet

Parliaments are made to share power.

Some people are worried that the next election could lead to a “hung parliament”, requiring power sharing arrangements between parties and independents. But Parliaments always involve power-sharing: between interest groups, communities and political movements; across the upper and lower houses; within parties (via factions); and between parties.

In a coalition government, parties make a formal agreement to share power.

In a minority government, the government relies on the ongoing support of crossbenchers.

A hung parliament is where no party or coalition has a majority of seats in the lower house (the House of Representatives)

Power sharing is common

Minority and coalition governments reflect the will of voters, are usually stable and constructive and are commonplace – including the very first Australian Government.

Minority and coalition governments make the conditions under which power is shared particularly visible and accessible. These forms of power-sharing government occur when a government must negotiate with MPs on the “crossbench” between the Government and the Opposition.

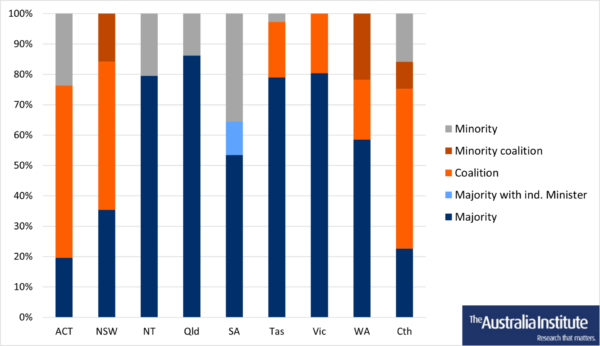

Australians have not given one party or coalition a majority of the vote in a federal election since 1975. All Australian states and territories have had minority/coalition governments in the last 20 years, and three have them now. After the last Tasmanian election, then Opposition Leader Rebecca White predicted,

It is very likely that Tasmania will continue to elect minority governments.

Power-sharing parliaments are also common internationally: New Zealand has not had a single-party government since 1994; Canada, Croatia, France, Portugal, Spain, Taiwan and the Nordic

countries, among others, currently have power-sharing governments.

Power sharing in Australia

After Federation in 1901, Australian governments shared power because no party held most seats. The “majority government” concept only emerged after two parties fused in 1909.

Australia’s most successful power-sharing arrangement is the Coalition agreement between the Liberals and Nationals. Many treat the Coalition as a single major party—but the Liberals and Nationals are distinct parties with different ideologies and policy platforms.

The Coalition Agreement is re-negotiated and recreated as power and priorities shift between the parties. The 2010–13 Gillard Labor Government is the only minority federal government to be elected since 1940, although the Morrison Coalition Government twice lost its majority: in 2018–2019 due to a by-election, and in 2021–2022 due to a defection.

Power-sharing under the Gillard Government did not affect its workrate: during its tenure, it passed over 500 pieces of legislation—the highest daily rate of any Australian government. These included difficult reforms such as the Clean Energy Act, the Mineral Resource Rent Tax and the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

By contrast, the Albanese majority Government has passed fewer than 300 pieces of legislation so far.

Negotiating with crossbenchers in the House of Representatives may have eased the passage of legislation through the senate. The Senate is rarely controlled by any one party, meaning even so-called “majority governments” must share law-making power with the crossbench and opposition.

Labor/Greens in the ACT: Australia’s longest standing government

The longest-standing government in Australia is the coalition between Labor and the Greens in the ACT. This arrangement began in 2008 as a minority government, and in 2012, Greens MP Shane Rattenbury became a minister in the Gallagher Labor Government. The arrangement continued under Chief Minister Andrew Barr.

Australia Institute research finds that many of this coalition’s policies are popular nationwide:

- Spending on programs to reduce youth crime and incarceration (84% of Australians support)

- Pill testing at music festivals (64% support)

- A stamp duty to land tax swap (60% support).

Power-sharing parliaments are nothing to fear

Whether Australians vote for major parties, minor parties or independents is their choice, but they can make that choice without fear that a “hung parliament” would be dangerous or chaotic.

All parliaments share power, and some of Australia’s most successful governments are those where power is shared widely.

Related documents

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Gender parity closer after federal election but “sufficiently assertive” Liberal women are still outnumbered two to one

Now that the dust has settled on the 2025 federal election, what does it mean for the representation of women in Australian parliaments? In short, there has been a significant improvement at the national level. When we last wrote on this topic, the Australian Senate was majority female but only 40% of House of Representatives

The system is working, but big parties must heed voters and engage with minor parties

Tasmanians keep voting for a power-sharing parliament over the wishes of the major parties.

The election exposed weaknesses in Australian democracy – but the next parliament can fix them

Australia has some very strong democratic institutions – like an independent electoral commission, Saturday voting, full preferential voting and compulsory voting. These ensure that elections are free from corruption; that electorate boundaries are not based on partisan bias; and that most Australians turn out to vote. They are evidence of Australia’s proud history as an