With a Trump resurgence looming, the Australian Government’s fixation on AUKUS should not come at the expense of what we are frequently assured is one of the core components of the US-Australia alliance: shared democratic values, writes Dr Emma Shortis.

Last year, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s second American visit coincided with the resolution of yet another paralysing domestic political crisis for the United States. Having unseated the Speaker of the House for the first time in history – leaving the position empty for an unprecedented (expect to get very tired of that word this year) three weeks – Republicans finally elected Louisiana Congressman Mike Johnson.

Though the timing of the Speaker’s election meant that Albanese was unable to address a joint session of Congress, he was able to meet briefly with Johnson.

Sitting in front of a grand fireplace on a slightly too deep, cream-coloured wooden chair, Albanese offered his congratulations, warmly describing the Speaker’s election as “terrific”. As Johnson nodded politely, the prime minister moved to his biggest priority: the “important legislation required for AUKUS.” “We are,” he continued, “certainly hoping that the Congress can pass that legislation this year.”

Johnson came through for Albanese a few weeks later, shepherding legislation through Congress that will theoretically allow a future presidential administration to transfer the necessary technology for Australia to acquire nuclear-powered submarines. AUKUS was saved, for now. But at what cost, and at what risk?

What went unsaid in that October 2023 meeting is that the Australian government’s desperation to get AUKUS “institutionalised” before the end of the year was prompted at least in part by concerns that Johnson’s ideological ally might well be on his way back to the White House.

The man the Australian prime minister asked very nicely for help with AUKUS is a key Trump ally. In 2020, he wrote an amicus brief supporting efforts to overturn the election results. He is a Christian nationalist. The “appeal to heaven” flag that hangs outside his office signals his direct connection to the right-wing and religious mobilisation that led to the attempted insurrection on January 6, 2021.

He is now the highest legislative officer in the US government and third in line for the presidency. He will play a central role in the election this year, and whatever comes after.

Johnson and Albanese’s awkward meeting could be understood as yet another example of the strength of Australia’s alliance with the US, which, as the meeting itself demonstrates, retains its rock-solid bipartisan support. That alliance has long been understood as something that must sit well above the vagaries of domestic politics. But it could also be interpreted another way.

On the morning of January 7, 2021, then-opposition leader Albanese quote-tweeted incoming President Joe Biden. Apparently agreeing with Biden’s assessment of the violent assault on the United States Capitol as “bordering on sedition”, Albanese wrote: “Democracy is precious and cannot be taken for granted – the violent insurrection in Washington is an assault on the rule of law and democracy. Donald Trump has encouraged this response and must now call on his supporters to stand down.”

Three years later, Albanese was sitting next to a key supporter and architect of that violent insurrection, chatting politely for the cameras, all in the name of getting the AUKUS pact legislated.

Talking to people who do not share your politics is, of course, an integral component of diplomacy and a prime minister’s job. The fact that the Australian government was desperate to get the AUKUS legislation through before the US election season at least hints at concerns over having to deal with Trump again.

But the Australian government’s fixation on locking AUKUS down should not come at the expense of what we are frequently, but unconvincingly, assured is one of the core components of that alliance: shared democratic values.

On the third anniversary of a violent and nearly successful assault on those values, anxieties about what a victorious Trump might do with AUKUS – itself a short-sighted, outrageously expensive and poorly thought-through agreement – should be placed firmly alongside an examination of what is actually at stake for Australia and the alliance as the United States faces the biggest test of its democracy in generations.

Johnson gave the Australian government the legislation it so desperately wanted. What if he also helps give the White House back to Trump? What then? Will the Australian government describe that election (or otherwise) as “terrific” too?

We know what a second Trump administration would look like – Trump and his supporters have told us. There would be no “shared democratic values” under a second Trump presidency. Of particular concern to our own security alliance should be Trump’s plans to pack the military and Department of Defense with loyal toadies and then use them to attack the rule of law.

Many of the assailants on the Capitol three years ago were military or police veterans. Australian short-sightedness and adherence to “bipartisanship”, the politics notwithstanding, ties us ever closer to a military power that is already struggling with right-wing extremism, and risks tying us directly to a version of that controlled entirely by Trump.

In an alliance allegedly built on shared democratic values, “bipartisanship” should never mean identifying ourselves with fascists. And yet, that is exactly what this government is risking.

“Democracy,” as Prime Minister Albanese has said more than once, “is precious”. In 2024, we can hope that our closest ally will continue to agree. But we should also prepare ourselves for a situation in which that hope is dashed. What then?

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

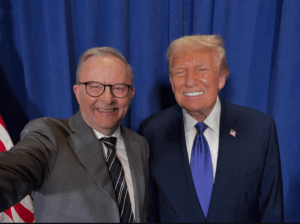

Can Albanese claim ‘success’ with Trump? Beyond the banter, the vague commitments should be viewed with scepticism

By all the usual diplomatic measures, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s meeting with US President Donald Trump was a great success. “Success” in a meeting with Trump is to avoid the ritual humiliation the president sometimes likes to inflict on his interlocutors. In that sense, Albanese and his team pulled off an impressive diplomatic feat. While there was one awkward

Donald Trump cannot make the Epstein files go away. Will this be the story that brings him down?

Conspiracy theories are funny things. The most enduring ones usually take hold for two reasons: first, because there’s some grain of truth to them, and second, because they speak to foundational historical divisions. The theories morph and change, distorting the grain of truth at their centre beyond reality. In the process, they reinforce and deepen

It shouldn’t be this difficult to condemn plans to commit a crime against humanity

Australians, by and large, have seen America as an ally critical to our national security. But in just a few short weeks, Donald Trump has shown his administration is a threat to Australia and the world’s security. Australia may not be able to stop Trump from creating chaos, but we will undermine our own security if we don’t stand up for ourselves and for our values.