One way to improve the “dumpster fire of dumb stuff” which is Australia’s housing policy

Everyone agrees we need to do something about housing in Australia. But first we need to ask a very obvious, but often ignored question: what is housing is for?

Is it a safe and secure place for people to live? Or is it a place to make a small minority of people rich?

The answer is important because the housing market over the last two decades has shown that it can’t be both.

Since the turn of the century, investors have flooded into the market, pushing up house prices, outbidding first home buyers, and making housing less affordable.

With the Reserve Bank now cutting official interest rates, house prices are going to grow even faster, and these rising house prices are going to attract even more investors.

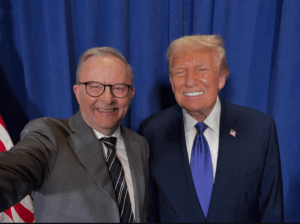

After an election where the issue of housing affordability was hotly debated, first home buyers struggling to break into the market are likely to watch as rapidly rising prices leave them further behind.

The major party’s policies on housing affordability fell into two categories.

The first are those that increase supply, which in the long run will make housing more affordable.

The second are those that gave some financial advantage to a particular group of home buyers, most often first-home buyers, that would increase demand, push up prices, and ultimately make housing less affordable.

Overall, the major party’s offerings on housing are best described as a dumpster fire of dumb stuff.

What neither side offered were policies that deal with the underlying cause of unaffordable housing, the explosion in investor demand for housing.

The introduction of the 50% capital gains tax (CGT) discount in 1999, which makes half the capital gains on investment properties tax free, meant that making money from rising house prices suddenly became an attractive tax strategy. Combined with negative gearing, speculating in housing made sense from a tax perspective, and banks were quick to encourage people to borrow against the equity in their homes. Investors rushed into the housing market, increasing house prices and pushing out first-home buyers.

The obvious solution is to crack down on the CGT discount and negative gearing. But Labor has so far been reluctant to make these changes. Fortunately, there is another policy lever the government can pull.

This other option is the boringly named macroprudential policies. These allow the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) to restrict leading to certain groups in the economy. In this case, it could restrict lending to property investors.

Why do this? Because we know that cutting interest rates makes borrowing more affordable. But what if, as the Reserve Bank cuts interest rates, this only benefitted people wanting to buy a home to live in?

By restricting lending to investors, the interest rate on investment loans would go up. Investors wouldn’t get the benefit of the lower rates, and owner-occupiers, in particular first home buyers, would have the advantage.

This is not a new idea.

These macroprudential policies were used between 2014 and 2018. At this time APRA was worried, not about housing affordability, but about financial market stability. But their restrictions saw lenders increase interest rates on investment loans by between 0.5% and 1%.

From late 2017 to mid-2019 investor loans dropped, and residential property prices fell a modest 9%. Over that two-year period incomes rose faster than property prices and for the first time in a long time, housing became more affordable.

The newly reelected Labor Government will have to act fast. The Reserve Bank is likely to continue lowering interest rates.

For years successive governments have promised more affordable housing while aspiring first home buyers have watched their dream of home ownership crushed under rising house prices.

They’re angry and frustrated that after doing all the right things they still can’t buy a home.

Reassurances from the government that additional supply will eventually make housing more affordable are unlikely to cut it with voters – especially if this new term of government begins with rapidly rising house prices.

Ultimately if the government wants to solve the crisis in housing affordability it will need to reform negative gearing and the CGT discount, combined with more housing supply. But in the short term, increasing the interest rates on investment loans will give first home buyers a fighting chance.

After an historic victory at the last election, the Labor party should not be complacent. Housing is an issue that shifts a lot of votes. And if those locked out of home ownership see things getting worse, in three years’ time they will rightly hold the government to account.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

How bad policy created a housing crisis

The capital gains tax concession and negative gearing have worked together to make housing less affordable and exacerbate inequality.

The Wage Price Index shows pay packets are up. So why doesn’t it feel that way?

The latest figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics show wages are growing at a reasonable rate, but a deeper look shows a big problem might be about to bite Australian workers.

Old habits die hard | Between the Lines

The Wrap with Matt Grudnoff This week, we published important research that looked at terrible flaws in the GST that are costing Australians billions of dollars in important government services, like health, education, housing, and infrastructure. When the GST was introduced, it was promised to be a growth tax that would help make the states