by Richard Denniss.

[This article originally appeared on The Guardian Australia 19.09.2018]

The royal commission Australia really needs is one into the spectacular – almost complete – failure of our regulators to protect the vulnerable from the greedy. While it is clear that many of our so-called watchdogs are little more than lap dogs, what is less clear is why. It’s time that Australians found out why those tasked with protecting us from exploitation have wound up protecting those who exploit us.

Like the royal commissions into the banks, the abuse of children in institutional care, the abuse of children in Darwin’s Don Dale prison or the water stolen from the Murray Darling basin, the royal commission into the aged care sector will inevitably reveal shocking systemic failures with devastating impacts on vulnerable people who were incapable of looking after themselves.

Royal commissions into aged care and (potentially) the electricity industry are good ideas. But it’s time we raised our sights and inquired into why it is that NGOs and journalists are better at uncovering scandals than the regulatory bodies which are given billions of dollars per year to perform exactly that task?

It’s hard to believe that only two years ago we were told it was an insult to the hardworking people at Asic and Apra to suggest we needed a royal commission into the banks. But then again it’s only two years since a Wollongong University student used her Facebook network to uncover systematic wage theft from young workers. If only the Fair Work Commission, or the police, thought of such a cunning plan as to ask young people what they were getting paid and compared those numbers to the relevant awards.

One of neoliberalism’s best tricks was to convince people that the more government services we privatised and outsourced, the less need there would be for regulation and enforcement. What could go wrong?

Who would have thought that companies with a legal obligation to maximise profit would put the interests of their shareholders ahead of the interests of vulnerable people who were easy to exploit? Who would have thought that companies with armies of lawyers at their disposal would make better use of a “level playing field” than people without the time or money to fight for their rights? Just because a boxing ring is a level playing field doesn’t make a fight between a heavyweight and a featherweight an even match.

According to the neoliberal version of economic theory (there are other versions), the owners of privatised aged care centres, refugee detention centres and vocational education would all compete with each other to drive the quality of their services up and the cost of providing those services down. How good is that? But, like the argument that corporate tax cuts fix budget deficits and wage cuts help workers, there is simply no evidence to support the theory that bank customers, aged care customers and detention centre “customers” are so good at looking after their own interests that regulators can abandon random inspections and rely on a “light touch” instead.

Neoliberal theory suggests that, just as customers are free to shop around for the best coffee at the best price, or the best airfares at the best price, “empowering” citizens to shop around for the best aged care, childcare, vocational education or electricity would deliver better services at a lower cost. But they were wrong. Dangerously wrong.

It’s hard enough for busy adults to navigate the terms and conditions on their phone plans and car rental contracts. In turn, it is negligent to assume that vulnerable people navigating new systems at a time of personal crisis can use their “consumer power” to look after themselves. And, as the royal commission into aged care will soon show, dementia patients, the very frail and elderly people, or those with poor language skills find it hard to assert their right to quality care.

This should come as no surprise to anyone who has ever worked in or even visited an aged care centre, but at the heart of the theory that privatisation will provide better services at lower costs is the absurd assumption that the vulnerable can stand up for themselves.

There is no doubt that the royal commissions into the banking and aged care sector will recommend stronger laws to protect the vulnerable and more funding for our regulators. Such changes have the potential to make things at least slightly better. But while Band-Aid solutions can sometimes be better than nothing, they can also hide the wound that is festering underneath.

So if we really want to understand why so many scandals are occurring in so many sectors – and that’s a big “if” for a body politic that has resisted a federal corruption watchdog for decades – we need to look for the underlying cause of the systematic failings of our regulators. We need a royal commission into regulatory culture in Australia to understand why so many of those tasked with protecting the vulnerable think that unannounced inspections of care facilities are “intrusive” and why our financial regulators think they need to consult with the banks, before issuing press releases about bank misconduct.

When it comes to border protection, recreational drug use and welfare fraud, Australians have been told that we need “tough cops on the beat” and “zero tolerance”. But when it comes to billion-dollar corporations ripping off vulnerable people, we are told we need to engage in dialogue to create a culture of voluntary compliance. It’s not just income that is unevenly distributed in Australia, it is oversight and punishment, and it’s time we inquired into why.

Richard Denniss is the chief economist for the Australia Institute. His Quarterly Essay, Dead Right: How Neoliberalism ate itself and what comes next, is available now.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

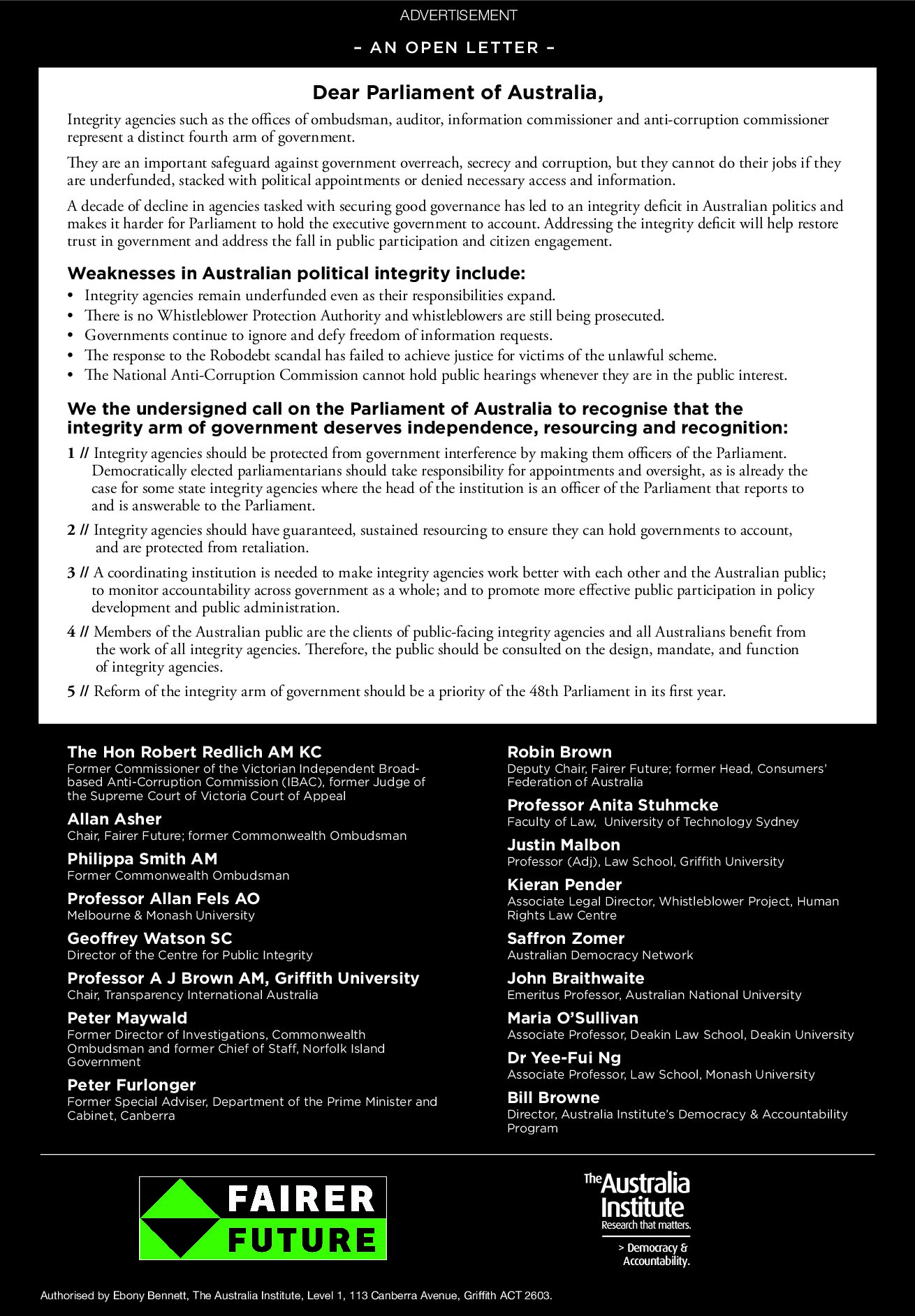

Open letter calls on newly elected Parliament to introduce Whistleblower Protection Authority, sustained funding for integrity agencies to protect from government pressure.

Integrity experts, including former judges, ombudsmen and leading academics, have signed an open letter, coordinated by The Australia Institute and Fairer Future and published today in The Canberra Times, calling on the newly elected Parliament of Australia to address weaknesses in Australian political integrity. The open letter warns that a decade of decline in agencies

The election exposed weaknesses in Australian democracy – but the next parliament can fix them

Australia has some very strong democratic institutions – like an independent electoral commission, Saturday voting, full preferential voting and compulsory voting. These ensure that elections are free from corruption; that electorate boundaries are not based on partisan bias; and that most Australians turn out to vote. They are evidence of Australia’s proud history as an

Bell’s departure is overdue, but this crisis is not all her fault. Here’s why

Genevieve Bell, vice-chancellor of the Australian National University (ANU), has announced her resignation. Many will welcome this news.