Past the Pendulum: thinking inside The Cube

New research from the Australia Institute’s Democracy & Accountability Program suggests new models are needed to interpret national two-party preferred polls

The latest Newspoll finding a national two-party preferred swing of 5.5% to Labor has election watchers and campaigners reaching for their electoral pendulum to work out what it all means come Saturday. The Australian’s Newspoll page predicts Labor would win 85 seats to the Coalition’s 60.

So why are commentators talking about the disproportionately difficult electoral battle Labor faces, and the “must win” seats? And why are the betting markets still pricing in roughly one in three odds of a Coalition win?

We know some of the standard answers. Different polls vary. There’s only one poll that counts. And remember the “unlosable election” in 2019? No one wants electoral egg on their face twice in a row.

What’s more, safe and marginal seats are not evenly distributed. Of the 16 ultra-marginal major party seats, 12 are held by Labor and only three by the Coalition. Labor has more to lose. According to the pendulum, if Labor won 51.5% of the vote it would be neck and neck with the Coalition on 72 seats each.

Would Labor really be four seats short of a majority on the back of a 3% national swing, and a solid 51.5% of the two-party preferred vote? This approach gives undue weight is given to individual seats, not broader patterns. New research from the Australia Institute offers an alternative to the electoral pendulum that avoids this trap.

Pendulum predictions aren’t perfect

The electoral pendulum has been a staple of Australian political analysis since its introduction by psephologist and political scientist Malcolm Mackerras in the early 1970s. The sight will be familiar: a spread of Labor and Coalition seats, with the safest at the extremes and the most marginal in the middle.

It’s a useful tool for translating what a national swing might mean for the net seat take. Unfortunately, because it uses individual seat data to predict net seats, campaigners and commentators alike have taken to assuming the pendulum predicts results in individual seats. That’s a mistake, as Mackerras himself is at pains to point out.

National swings are never uniformly distributed. Just ask the former Labor member for Lyons, Dick Adams, whose 12.3% margin put 49 seats between him and the Coalition in the 2013 election. A swing of 3.6% against Labor “should have” cost the party 12 seats. They lost 17, including Lyons – though 16 Labor seats more marginal than Lyons were spared.

What does the evidence tell us?

Having heard from backbenchers’ offices that they take seriously the position of their own electorates on the pendulum, The Australia Institute’s Democracy & Accountability Program decided to calculate how accurate the pendulum has been as a predictor of individual seat changes.

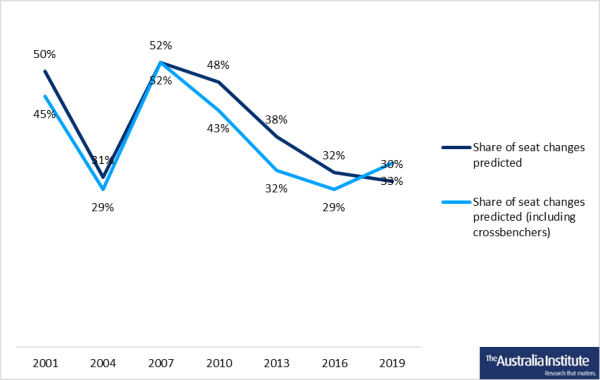

By this measure, the pendulum is a poor predictor – and has been getting less accurate since 2007. In 2007 it predicted 52% of all seat changes, down to 33% in 2019.

Figure 1: Seat changes predicted by pendulum

Think inside the Cube

Poking holes in the pendulum is of little use if there is no alternative. What can we add to the toolbox? Enter the Cube Law. First applied to Australian elections in 1962 by political scientist Joan Rydon, the Cube Law ignores individual seats altogether, instead predicting total seat numbers based only on the ratio of the cube of the vote received by each party.

It may sound complicated, but the effect is that at 50% two-party preferred the seats are split evenly, but every one percentage point difference results in a roughly three percentage point change in seats. A party that wins 51.5% of the vote can expect 55% of the seats.

The Cube Law comes close

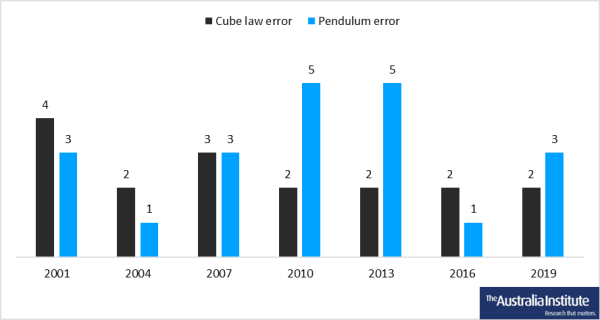

And how does the Cube Law alternative do? Well, about as well as the pendulum does: over the last seven federal elections, the Cube Law comes closer in three elections and the pendulum in three, and the two models tie once.

Figure 2: Error, Cube Law vs pendulum uniform swing

The advantage of the Cube Law is that it avoids individual seats and the illusion that whether they stand or fall turns on the uniform swing.

What does the Cube Law have to say about the next election? Well, it suggests that the Coalition could win majority government even with a 0.5% swing against them, whereas the pendulum finds that they require a 0.2% swing towards them. Both models agree that on a perfectly split 50%–50% two-party preferred, the parties win 72 seats each. But whereas the pendulum suggests Labor needs a 3.3% uniform swing to win government, the Cube Law expects a Labor majority on a 2.5% swing.

Of course, there’s only one poll that counts and all models have their weaknesses. But relying on the electoral pendulum alone is complacent. For a multifaceted analysis, it’s time to think within the Cube.

Related research

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Victoria’s Electoral Laws Need Truth in Advertising and Fair Rules for New Entrants

Victoria should adopt truth in political advertising and address the unfairness created by its donation cap and public funding model.

Women still underrepresented in Australian parliaments

Ahead of International Women’s Day on 8 March, the Australia Institute has crunched the data on women’s representation in Australian parliaments.

More work needed despite launching of National Anti-Corruption Commission

Australia may finally have a national anti-corruption watchdog, but we still have a long way to go to reach genuine accountability and transparency in our system of government.