“Intolerance of corruption is essential to the survival of our representative democracy and way of life,” said the late David Ipp QC, former commissioner of the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption.

Australian voters certainly appear to agree. New Australia Institute research shows that three-quarters of Australians (76 per cent) say integrity issues are more or equally important this election as last, and for good reason.

Governments exert huge power and control over the liberties and lives of citizens, and appoint people to positions of power and authority on government and independent statutory bodies. Governments spend billions of dollars of public money each year on our behalf, and the public is entitled to expect they exercise these powers for the public’s benefit.

All of this makes Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s recent attacks on the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption as inexplicable as they are unacceptable. It is one thing to propose a model for a federal integrity commission that legal experts regards as weak and ineffectual; it is quite another to publicly undermine state anti-corruption bodies.

The Prime Minister labelling NSW ICAC a “kangaroo court” demonstrates either a fundamental misunderstanding of ICAC’s role or a wilful effort to misrepresent it.

For a start, ICAC is not a court and does not have the power to make findings of guilt or innocence, as ICAC commissioner Stephen Rushton told a parliamentary review. It’s much closer to a royal commission than a court, and Australians have all seen the power of royal commissions to expose wrongdoing and maladministration – whether in the banking sector, the aged care sector or the systematic abuse of children within churches and other institutions (and the cover-ups that allowed the abuse to continue for years and years).

One of the Prime Minister’s chief concerns appears to be that corruption watchdogs are able to conduct public hearings, which are sometimes embarrassing to public officials, including members of parliament. But it is absurd to think secret proceedings can effectively expose corruption. Corruption relies on secrecy to metastasise.

Corruption also does not trouble itself with state or territory borders, which is why the ACT Legislative Assembly should be commended for establishing the ACT Integrity Commission, leaving the Commonwealth the only jurisdiction without an anti-corruption body. For two years the ACT Assembly held inquiries and explored the scope, jurisdiction and powers required for its integrity body. When the legislation was tabled, Labor, the Greens and the Liberal opposition spent weeks debating amendments – mostly from the opposition – while attempting to find common ground, and the ACT Integrity Commission began operating in 2019. In contrast, the federal government never put its proposed Commonwealth Integrity Commission to the Parliament for debate.

The lack of “truth in political advertising” laws is felt most acutely during election campaigns, and the perceived lack of integrity of politicians is an understandable focus of the current debate, especially during an election when so many voters are weighing the merits and deficits of candidates and judging the record of the incumbent government. But politicians should not be the only ones under the microscope. News reports revealing that police have given secret briefings to state governments about organised crime “running rampant across Australia” also highlight the importance of exposing corruption within government agencies and among public servants.

Police have apparently briefed the NSW government that drug trafficking and money laundering has compromised the gaming and transport sectors, including ports. The briefings build on earlier warnings from the head of the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, Mike Phelan, that corrupt government officials and border insiders were helping organised crime smuggle drugs into the country. Phelan also said it was “extremely naive” to think organised crime had not penetrated Australian law-enforcement agencies.

Public servants can also be unwitting parties to corruption, as dodgy companies and criminal enterprises seek to corrupt processes such as the awarding of contracts or accreditation or licensing arrangements.

A decade ago, investigative journalist Linton Besser won a Walkley for examining 80,000 defence contracts and exposing $1.4 billion that was spent on travel (including Learjets), phantom contracts and sailing trips. A year later he exposed that thousands of allegations of graft, fraud and abuse of office had been made against federal government agencies and departments, with many of them never independently investigated.

Nothing much has changed since then, and the gaps in our federal integrity systems remain. A strong federal corruption watchdog is plainly only the start of reforms needed to restore our trust in government and politics.

David Ipp sadly passed away in 2020, but his advice is timeless: “Once citizens believe that government is corrupt, and that the very people who make the laws and government decisions are corrupt, they lose interest in acting for the public good. They become more likely to engage in corrupt conduct themselves. Avarice and greed become their predominant passion and government systems fall apart.”

The Australia Institute has launched a “Democracy Agenda for the 47th Parliament”, with dozens of proposals for democratic reforms for our next parliament to consider, including a corruption watchdog with teeth, truth in political advertising laws, strengthening the independence of appointments to the ABC board, and oversight of grants programs with ministerial discretion. Enshrining an Indigenous Voice to Parliament must also be at the top of any democratic reform agenda.

The good news is that the wave of dissatisfaction from voters in blue-ribbon Liberal seats like Wentworth, North Sydney and Goldstein, as well as strong support for MPs and candidates who have made integrity a key part of their campaigns, indicate that tackling corruption and boosting integrity is clearly important to the public. This is the integrity election.

Related research

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

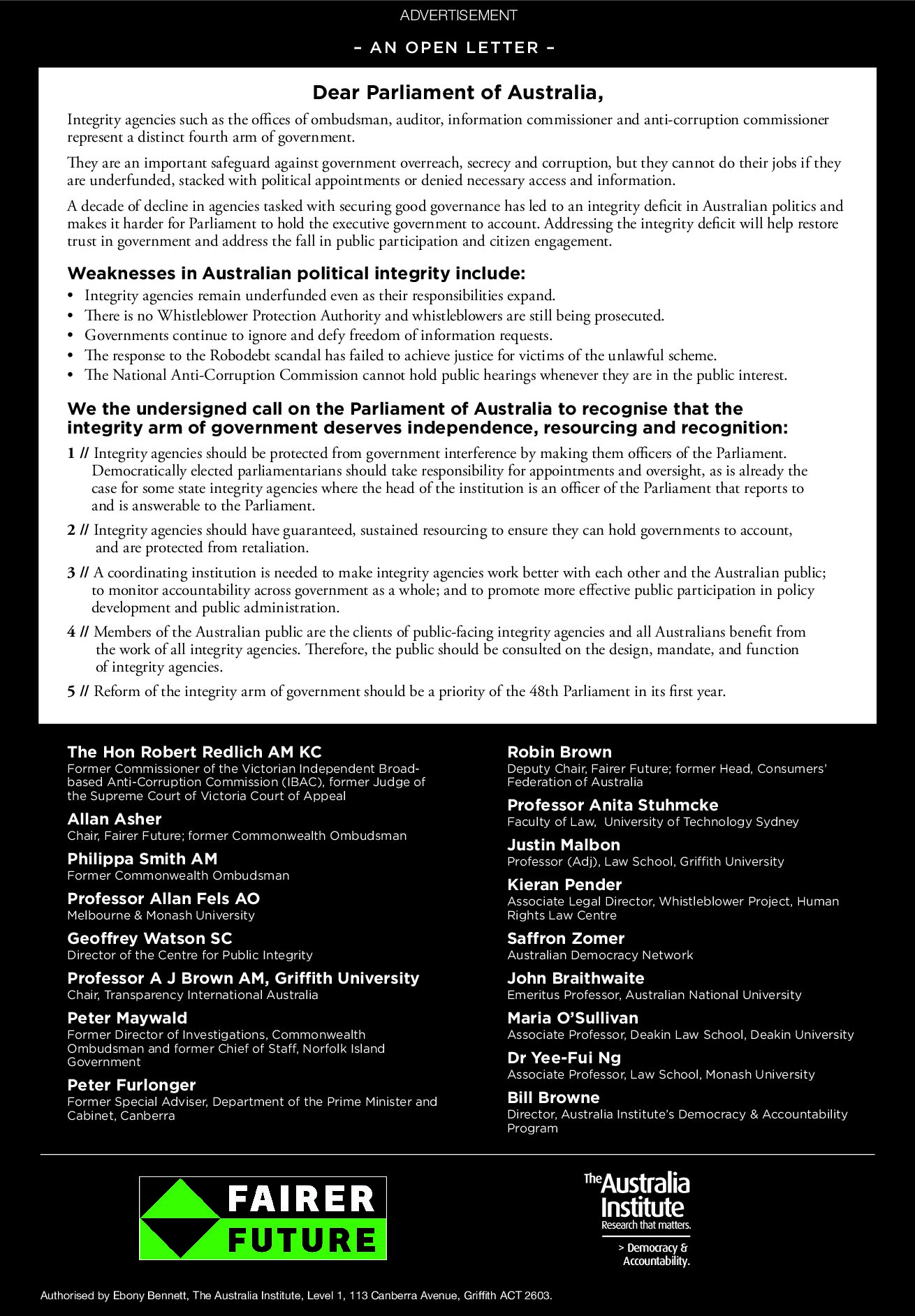

Open letter calls on newly elected Parliament to introduce Whistleblower Protection Authority, sustained funding for integrity agencies to protect from government pressure.

Integrity experts, including former judges, ombudsmen and leading academics, have signed an open letter, coordinated by The Australia Institute and Fairer Future and published today in The Canberra Times, calling on the newly elected Parliament of Australia to address weaknesses in Australian political integrity. The open letter warns that a decade of decline in agencies

Integrity 2.0 – whatever happened to the fourth arm of government?

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese came to office in 2022 promising a new era of integrity in government.

Secretive and rushed: Unpacking SA’s new electoral laws

As dramatic changes to South Australian electoral law pass the house of review (Legislative Council), voters could be forgiven for wondering “what just happened?”

A week ago, no one had seen the government’s revised Electoral (Accountability and Integrity) Amendment Bill 2024. Now, it’s set to become law.

Amy Remeikis and the Director of The Australia Institute’s Democracy and Accountability Program, Bill Browne, unpack how we got here … and what should happen next.