The 3 key arguments for the company tax cut make no economic sense, here’s why.

We often hear the government’s company tax cuts are ‘good for the economy,’ but are they?

The argument goes something like this: ‘everyone else is cutting company tax rates, if we don’t match their cuts no one will invest in Australia, we’ll lose money and jobs and wages will decline.’

That sounds bad. But what does it actually mean? And is it even true?

We examine a few key claims of big business company tax cut advocates and find they don’t stack up.

1 // We don’t want to join a global race to the bottom on company tax rates.

Around the world a trend toward cutting company tax rates seems to be emerging. Earlier this year the US passed a suite of tax changes, including cutting their federal company tax rate from 38 to 20 per cent (we’ll revisit what this really means in a moment).

Other countries like the UK, France and Belgium have also cut their rates or are trying to pass cuts through their own legislative processes.

Company tax cut advocates say that if we don’t fall into line and cut our rates we will become ‘unattractive’ as a destination for foreign investment.

There are two things worth examining here, firstly, what are we comparing when we compare one country’s company tax rate with another? Are we comparing apples with apples? And, secondly, is there a direct relationship between the company tax rate and foreign investment? Do company tax rate cuts actually lead to more foreign investment?

Is my country’s company tax rate bigger than yours?

The amount of tax a company pays is, as you can imagine, quite complicated.

Companies don’t pay tax on their ‘profits’ as they are understood in normal accounting terms. They pay tax on whatever the country considers their ‘taxable income’. Countries may have rules that exempt some parts of a company’s assets or profit from being taxed as a way to encourage certain behaviours or discourage others.

Many countries also have other tax arrangements that add to the company tax rate. For example, in the US, while the federal tax rate is 20%, when you take an average of all the individual states company tax rates, companies in the US end up paying around 25% in company tax (on whatever their ‘taxable income’ is).

Many companies also try to minimise their tax burden so they can maximise their profits and returns to shareholders. As Kerry Packer famously said,

“I pay whatever tax I am required to pay under the law — not a penny more, not a penny less. The suggestion that I am trying to evade tax — which is what you are putting forward — I find highly offensive…

“I don’t know anybody that doesn’t minimise their tax … Of course I’m minimising my tax. If anybody in this country doesn’t minimise their tax they want their head read.”

But a company’s ability to minimise their taxable income depends on the country’s tax rules and how they are enforced.

None of this is captured in the single figure we’re often asked to consider: the company tax rate.

So does cutting company tax increase foreign investment?

The company tax cut lobby argues that countries with lower company tax rates will attract more foreign investment and that foreign investment is “good for the economy”.

To understand whether this is true there are a couple of places we can look. The first is at which countries currently make up the majority of our foreign investment. Following the company tax cut logic we’d expect to find that only countries with higher company tax rates than our 30% rate are investing in Australia.

In fact, what we found when we looked at this back in January, 2017 is that among the 13 countries that had the greatest share of foreign investment in Australia, 9 had lower company tax rates than our own.

The second place to look is at Australia’s foreign investment over time. Our company tax rate has reduced from a peak over 49% in 1986, down to 30% by 2001. If company tax cut advocates are right you’d expect to see an increase in foreign investment over that period.

The basis for this argument is one, single report that found a 1% increase in the company tax rate would lead to a 3.72% reduction in foreign investment. So, in theory, if we actually increased our company tax rate to 31% we would see a decline in our foreign investment of 3.72%.

Company tax cut advocates use this theory to argue that the opposite is also true, if we cut company tax rates foreign investment will grow. You might think it’s a long bow to draw and we agree. But, if we follow that ‘logic’, foreign investment should have increased a whopping 71% from 1986 to 2001. Instead what we see is that foreign investment grew during the period of high company tax rates until the late 80’s and has remained, generally, between 3 and 6% of GDP over the last few decades.

2 // Cutting the tax rate doesn’t grow the pie, it just changes the shape of the slices.

While pie eating seems like a pretty Australian thing to do (cutlery or no cutlery), this part of the argument depends on us believing that: company tax cuts = increased foreign investment = a better economy = more jobs and increased wages for workers.

Firstly we should tackle some of the assumptions here. When people (usually business lobby groups) say things like “what’s good for business is good for Australia” the underlying message is: working Australian’s will be better off when businesses are making more money. This assumes that workers will somehow benefit from those profits. Benefiting from them would mean pay rises or more jobs or more secure jobs. In the case of company tax cuts what the business lobby is saying is: if the company pays less tax they have more money to spend on ‘other things’.

We’ve already seen that there doesn’t seem to be any real relationship between cutting company tax rates and increases in foreign investment. But we can still look at whether there is any benefit for workers in cutting company tax rates. Cutting the company tax rate from 30 to 25% will at least result, theoretically, in companies keeping 5% of their taxable income that previously went into government revenue. So what is likely to happen to this money?

What will those ‘other things’ be? Are they likely to be wage increases and new jobs?

To answer these questions we can look around the world, and here in Australia, at the connection between company tax rates and living standards.

When we mapped countries company tax rates against their living standards (which you can get a sense of by working out the GDP per capita) we found that there was no correlation between company tax rate and living standard. In fact, if anything, a country is slightly more likely to have a higher living standard if they have a higher company tax rate. So, on a global level at least, lower company tax rates don’t mean better living standards.

But what about in Australia? If company tax cuts are good for workers you’d expect that since the peak of company tax rates at 49% in 1986 to their current low of 30% you’d have seen wages increase. Instead what we see is that, as a share of our gross domestic product, wages have fallen by 13%.

When people talk about GDP what they’re talking about is ‘the pie’; everything in the whole economy that was bought and sold in a year; all the ‘economic’ activity, including wages. So despite a 19% decrease in the company tax rate, workers share of ‘the pie’ has declined by 13%.

So where does the money from company tax cuts actually go? Who’s getting more pie?

While we’ve seen that lowering the company tax rate doesn’t increase ‘the pie’ in Australia, it must do something for the business lobby to be so excited about it. And since Australian workers aren’t seeing any increase in their share of ‘the pie’, who is benefitting?

If we keep looking at wages what we find is that decline in the share going to workers is almost matched by a corresponding increase in the share of GDP (‘the pie’) going to corporate profits — especially the financial sector. And while that’s worrying in itself it doesn’t tell the full story about the corporate tax cuts.

To understand a bit better we can look at a few things.

Firstly, what do CEO’s themselves say they’ll spend the tax cuts on? Good question. When the CEO’s of the Business Council’s 130+ member companies were asked in a secret Business Council of Australia survey to nominate one of four options as their preferred response to the company tax cut in Australia, only 17% nominated higher wages or more jobs. Over 80% selected either returning funds to shareholders, or more investment.

Secondly, if we look at what has actually happened in the United States after the implementation of Trump’s tax cuts we can see that it resulted in big benefits to rich shareholders through share buy-backs and dividend increases, and an increase in mergers and acquisitions that benefit corporate executives and make big business even bigger.

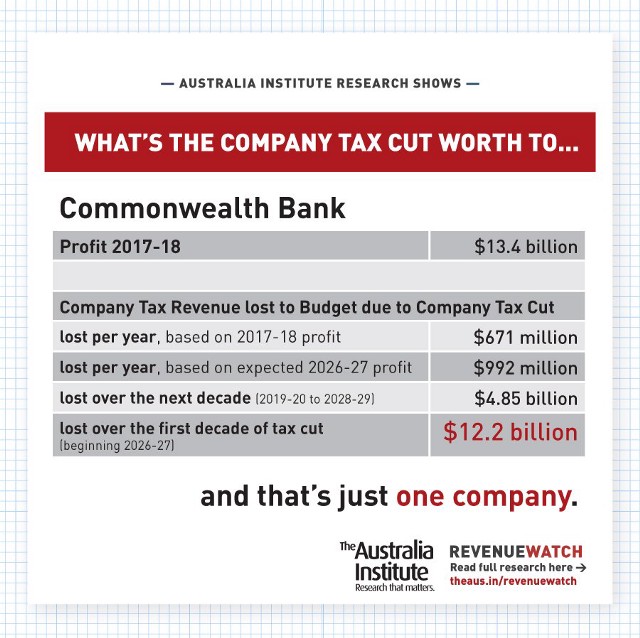

And thirdly, now that we’re in company reporting season we can better understand what this tax cut means for some of Australia’s biggest companies. For the Commonwealth Bank, for example, the first decade of the tax cuts alone is worth $12.2 billion. You read that right, $12.2 billion, for one company.

So what about Australian shareholders then? Surely the proposed company tax cuts at least benefit them?

So what about Australian shareholders then? Surely the proposed company tax cuts at least benefit them?

Nope. Not even Australian shareholders get the benefit because of Australia’s system of dividend imputation.

Dividend imputation is a scary term for a tax rule that means you won’t pay double tax on any dividends you get from your shares. For example, if you are a wealthy shareholder, your marginal tax rate is 45% (the top personal income tax rate) and you pay the Medicare levy, you currently pay 47 cents tax for every dollar of share dividend you receive. But your share dividends have already gone through the company tax wringer and paid 30 cents on the pre-tax value of the dividend. So the tax office grosses your income up, taxes you at 47 cents and gives back 30 cents as franking credits.

If you think this seems like crazy and confusing double handling you’re not wrong, but under the proposed company tax cut this would simply mean, come tax time, you would pay your 47 cents in the dollar on (most likely) a bigger dividend but only get back the 25 cents the company had already paid. What you gain in lower company tax you lose in less franking credits. The net effect is that your dividends are taxed at 47% whether the company tax rate is set at 25 or 30%.

So Australian shareholders won’t benefit, but foreign investors will. That’s why Paul Keating asked,

“… do you know any foreigners you want to give 5% of our national company income to? Any deserving cases out there? Or should we leave the company tax rate where it is, as a withholding tax, for the promotion of Australian investment and for the benefit of Australian taxpayers?”

3 // Australians aren’t convinced because the tax cut arguments (clearly) aren’t convincing.

Company tax cuts poll badly across the board. A majority of voters from every party don’t like them.

Advocates for the cuts say that Australians might not like the tax cuts, but that’s because they don’t know what’s good for them.

Since we can see that company tax cuts don’t correlate with increased foreign investment, that Australian workers won’t see improvements in their living standards, and that even Australian shareholders won’t benefit, it seems Australian’s opposed to the cuts are a lot smarter than the business lobby thinks they are.

When asked what they believed companies would most likely do with the company tax cut 78% of respondents selected: give it to shareholders, more investment, or increase executive pay; and only 17% selected increase wages or ‘none of these’ (i.e. something else, like more jobs).

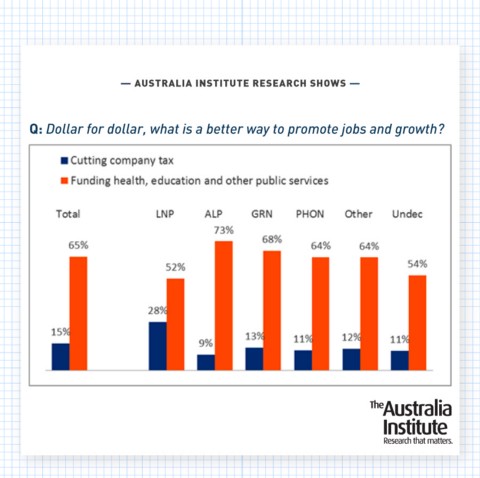

And when asked ‘what is a better way to promote jobs and growth?’ 65% said funding health, education and other public services.

Australians know it’s not true that: company tax cuts = increased foreign investment = a better economy = more jobs and increased wages for workers.

But it is true that: cuts to company tax = cuts to revenue = cuts to services.

One of the most sinister things about the proposed tax cuts is that they won’t be implemented in full for ten years. Treasury, the government department responsible for number crunching the budget, comes up with what they call the ‘forward estimates’. These forward estimates allow them to look at budget measures being introduced and make predictions on what the economy and the budget might look like as a result of them.

There are obviously limits to this since economics is not an exact science (or some would argue even a science at all), so the forward estimates period is only three years beyond the current financial year. The proposed company tax cuts fall outside that window so we don’t have any way of knowing what they’ll mean for our budget.

But a $65 billion tax cut means a $65 billion decrease in our national budget and that has to be accounted for, either in cuts to expenditure (which really means government services like health, education and infrastructure) or increases in the budget deficit.

The vast majority of Australian’s have smelled the rat in the company tax cut debate.

The problem isn’t that they “just don’t get it” on company tax, it’s that bad policy makes bad politics.

To hear more from both sides of the argument listen here to ABC Brisbane’s Focus with Emma Griffiths, where Ben Oquist, Executive Director at The Australia Institute, explains why the cases put forward for the company tax cut simply don’t stack up.

And for a deep dive into company tax cuts you can read one or all of our great reports here.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

10 reasons why Australia does not need company tax cuts

1/ Giving business billions of dollars in tax cuts means starving schools, hospitals and other services. Giving business billions of dollars in tax cuts means billions of dollars less for services like schools and hospitals. If Australia cut company tax from 30% to 25% this would give business about $20 billion in its first year,

Company tax cuts would do little to boost investment and hurt everyday Australians – new analysis

When Treasurer Jim Chalmers brings the nation’s economic leaders together next month, don’t be surprised if big business pushes – yet again – to cut the company tax rate.

The Liberal Party defies its own history on tax

For decades, the Liberal Party has prided itself on being the “party of lower taxes”.