The RBA raised rates in March and May despite its own analysis saying they were not needed

The Reserve Bank’s own research showed that raising rates after February would only increase unemployment, not lower inflation

Last week the Reserve Bank released documents as part of a freedom of information request on modeling the bank had undertaken on a recession of severe economic downturn due to the impact of interest rate rises. Most media coverage focused on the estimate that there was a 50% chance of Australia falling into a recession and as high at 80% chance under various scenarios. But the big story was that the documents showed analysis done in February, when the cash rate was 3.35%, reveled there was no real need to raise rates further in order to lower inflation.

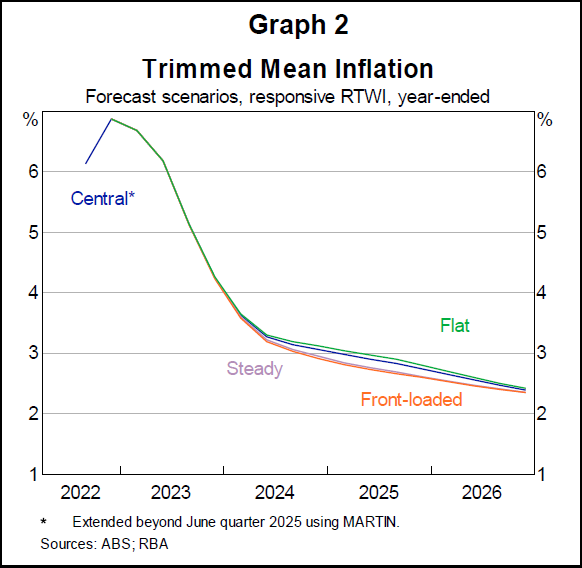

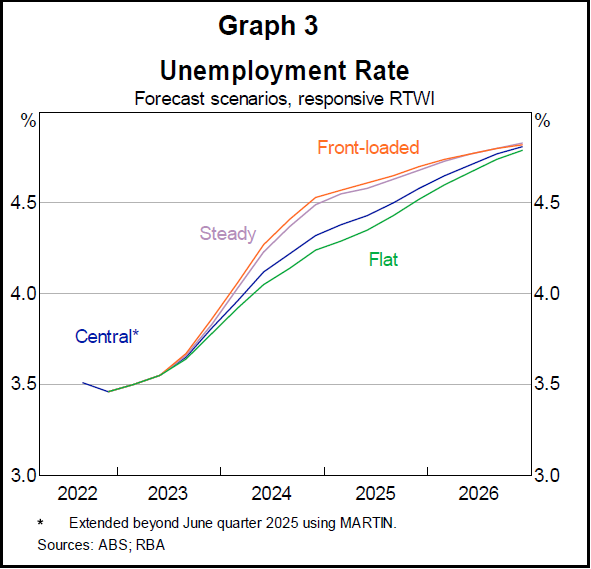

The two graphs above are from a section titled “Alternative Monetary Policy Paths”, in which 3 scenarios are presented:

- Front loaded – The cash rate increases by 50 basis points each Board meeting to 4.8 per cent in May 2023.

- Steady – The cash rate increases by 25 basis points each Board meeting to 4.8 per cent in August 2023.

- Flat – The cash rate remains at the level of 3.35% (as it was in February).

The analysis found was that “All cash rate paths bring inflation within the target band by the end of the SMP forecast horizon (mid-2025).”

The only difference was the speed at which inflation returned below 3%.

But, crucially, the difference is negligible.

The graph above presenting the options of the trimmed mean inflation (the RBA’s preferred measure of core/underlining inflation) under the 3 scenarios shows no discernable difference at all in inflation until mid 2024. And even from then the difference is of such small margin that there is no real economic basis for pursuing one path over another.

The “front loaded” case is predicted to bring inflation to 3% during the second half of 2024, and yet the model also predicts the flat scenario (in which the cash rate was kept at 3.35%) inflation at that same time would be around 3.2%.

That small difference in inflation is essentially indistinguishable in a macroeconomic sense.

Essentially the RBA’s own analysis was saying the difference in between keeping the cash rate at 3.35% and raising it to 4.8% was around 0.2% of inflation by September next year.

But while the 3 scenarios are projected to make little difference to inflation, they have a significant impact on unemployment.

Under the “front-loaded” scenario by the time inflation it predicted to reach 3%, unemployment would be 4.5%. The “flat” scenario at the same point would see unemployment projected to be around 4.2% – around 50,000 fewer people out of work.

The analysis also showed that raising the rates increased the risks of a recession. Despite this, the RBA board still raised the cash rate in March to April to 3.6% and then again in May to 3.85%.

Was the board even shown this analysis?

It is clear the Reserve Bank seems more worried about raising unemployment than it is lowering inflation. Wedded as its thinking is to the concept of the NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment), in which it believes the only way to keep inflation down is to raise unemployment to at least 4.5%, the RBA has now raised the cash rate twice despite its own analysis saying the difference in inflation would be minimal and would make no difference ever the next year.

These two increases raised the interest repayments of a $500,000 loan by around $150. All for no real impact on inflation, but a real impact on unemployment.

The time has come for the RBA to stop raising rates in order to create more unemployment and to acknowledge that any more rate rises will only increase the risk of sending Australia into a recession.

Related research

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Fearful and frozen: Why the Reserve Bank continues to err on rates

The RBA’s failures have real consequences. It should go back and closely reread the recommendations of the RBA review, particularly the ones that encourage it to open up to new and diverse viewpoints.

Delayed RBA cut is welcome, but borrowers are still lagging

The RBA has cut interest rates – five weeks too late.

When targeting inflation, the RBA misses more often than it hits

With the fight against high inflation now over, will the Reserve Bank fail to learn the lessons of the past and allow inflation to fall below 2%?