The Wellbeing Framework needs to come up with more trustworthy ways to measure “Trust in Institutions”

The Wellbeing Framework attempts to measure how well Australians trust their institutions. Unfortunately, the government seems to have chosen measures designed to tell a good story.

The government’s Wellbeing Framework that was released in July is to be commended for looking outside the usual focus on economics to judge how well our nation and society are travelling. But, as the Framework itself makes clear “measuring what matters” is the key.

The Framework’s measurement of “cohesion”, which includes a matrix of measurements on “trust in institutions” leaves much to be desired. These metrics set the Framework up to measure things that are poorly counted, focus on narrow aspects, and ignore ongoing and structural concerns that will result in policy that will do little to improve wellbeing.

An immediate red flag is raised when looking at how the government measures the trust people have in institutions. The Framework considers trust in the health care system and trust in the police. Oddly, it uses the ABS General Social Survey which has only asked questions on these topics twice in 2019 and 2020. Not surprisingly the Framework suggests the progress on this metric is “stable”.

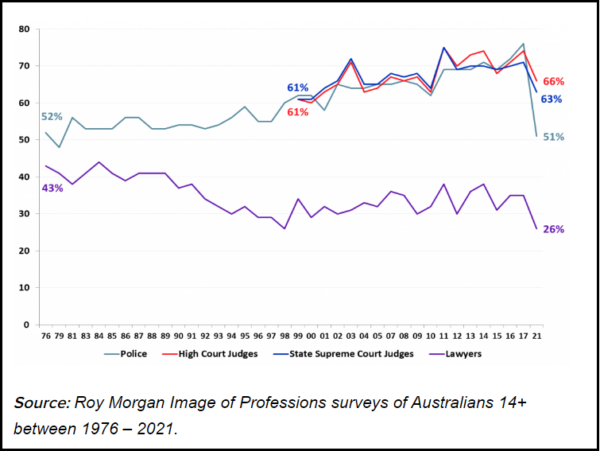

The government would be must better placed to use non-government surveys such as the Roy Morgan Image of Processionals Survey, which has results going back to the mid-1970s.

Far from suggesting for example the trust in police is “stable”, the Roy Morgan survey reported that “the image of Police has plunged by more than any other profession over the last few years, with a bare majority of 51% of Australians now rating Police ‘very high’ or ‘high’ for ethics and honesty. The rating for Police is down 25% from four years ago.”

Similarly, while it is worthy to measure the number of women in parliament, because as the Framework suggests “inclusivity of women in parliament relates to equality of representation political system”, that is only one aspect of diversity that is important in Australian society. There is no mention for example of representation of those from non-English or Anglo/Saxon backgrounds despite the large Asian representation within Australia’s populations. And because women currently represent 45.1% of federal parliamentarians the Framework has essentially chosen a measure in which the hard work has mostly been done.

The metric also only counts the Commonwealth parliament and thus excludes the gender balance in state parliaments and even local government – levels which greatly affect the lives of Australians. Similarly, the Framework would also do well to measure gender (and other) representation in the public service – especially at executive levels given the impact they have on policy development.

If the government is interested in “inclusivity” of parliaments it also could measure how proportional parliament is based on first preference votes vs seats. This however again might be an uncomfortable measure for the major political parties – but it would force governments to explain what they are doing to improve inclusivity in a manner that would require more than resting on their laurels.

The use of measures that seem designed to tell a good story might be while the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index has not been included. Over the past decade the perception of Australia as being free of corruption has fallen steadily.

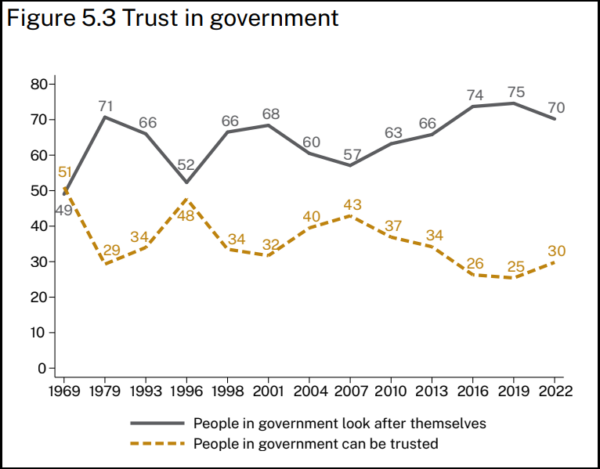

The Framework would also have been better served to make use of the valuable and long-running ANU Australian Election Study, which has data on trust in government going back to 1969.

That’s a more useful measure of trust in government than the one chosen by the government in the Framework, which comes from the OECD Better Life Index. That OECD Index uses a Gallup poll survey where respondents are asked if they “have confidence in the national government”. Such a question is much more likely to get a positive result than one which asks if people in government look after themselves or whether people in government can be trusted.

Similarly the Framework fails to consider electoral participation. And while our compulsory electoral system does generally deliver higher level of voting than other voluntary systems in other nations, it would be useful to measure eligibility to vote as a share of voting age population; enrolment as a share of eligible voters; turnout as a share of enrolled voters; and share of votes that are valid as a share of votes cast.

The Australia Institute recently investigated these aspects and found that electoral participation among the resident voting age population has fallen from highs in the second half of the 20th century in part because a larger portion of Australia’s voting age population is not eligible to vote. Several other countries extend voting rights to permanent residents, seemingly without issue – New Zealand is one of them. Failure to measure this means a failure to consider the problems that can occur when larger shares of the resident population are disenfranchised.

Lastly the Framework is woefully silent on human rights. While it does seek to measure “Valuing diversity, belonging and culture” it fails to consider measures such as incarceration rate, freedom of expression and freedom of association in this section. But again, such measures might tell an uncomfortable story such as the fact that 1 in 22 Indigenous men are in prison, which is two and half times higher that 1 in 55 black American men in prison.

All in all, the Wellbeing Framework is a largely failed attempt to measure trust in institutions. Were this merely an academic exercise in might not be of any great concerns, but the Framework is designed to drive policy. And the measures currently being used could potentially drive policies that ignores those aspects not being counted. And if that is the case, then Australians’ wellbeing is much less likely to be improved by this Framework.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

‘Perfect storm’: Government’s lies and half-truths burn through our precious trust

Northern Ireland political philosopher Onora O’Neill gave a series of lectures on “trust” in 2002, where she observed it is one of the most important social constructs we can hold:

The election exposed weaknesses in Australian democracy – but the next parliament can fix them

Australia has some very strong democratic institutions – like an independent electoral commission, Saturday voting, full preferential voting and compulsory voting. These ensure that elections are free from corruption; that electorate boundaries are not based on partisan bias; and that most Australians turn out to vote. They are evidence of Australia’s proud history as an

Gender parity closer after federal election but “sufficiently assertive” Liberal women are still outnumbered two to one

Now that the dust has settled on the 2025 federal election, what does it mean for the representation of women in Australian parliaments? In short, there has been a significant improvement at the national level. When we last wrote on this topic, the Australian Senate was majority female but only 40% of House of Representatives