Canberra resident and economist David Richardson has been attending the Budget ‘lock-up’ for the Australia Institute for 13 years. This year, he was banned.

The lock-up is where journalists, the opposition and crossbenchers, business groups, non-government organisations and other experts are given access to the details of the Federal Budget ahead of time. However, they are locked away unable to share the details until the Budget is formally released when the Treasurer begins his Budget speech.

The lock-up is part theatre, part political management. Journalists get to hear the government spin while locked up – but not the opposition’s view. Journalists are separated from civil society, business and unions during the lock-up for much the same reason.

Nonetheless, the arrangements are an important part of the country’s policy process. The lock-up is designed to ensure all players are given equal access to information at the same time. No one should get the inside word on a new policy announcement that might give them a share or currency trading advantage.

Security arrangements around the lock-up are tight. Mobile phones are banned and breaching lock-up confidentiality carries criminal sanction. Journalists must be associated with an accredited media organisation to gain entry. There are to be no leaks (other than those that government ministers have pre-arranged).

But some people are more equal than others and it is the government that decides who gets in. This year, David Richardson was refused entry under the guise of Covid restrictions.

Now, months later, the government is still refusing to reveal who it had let into the lock-up and what criteria it used to exclude others.

One person being excluded from the lock-up is, of course, not the end of the world. However, the Budget is a key part of Australia’s policy and democracy architecture. Millions of taxpayer dollars are spent putting it together and billions are allocated through decisions revealed in the Budget papers.

We have all learnt where disregarding democratic norms can take you. Democracy needs its practitioners to believe in it, not just pretend they do. It needs those sitting at its heart to adhere to established democratic principles and practices – and not only when it is convenient.

That is one of the reasons a federal anti-corruption commission is so needed – both to remove corruption where it exists and to be seen doing so. If they took the long view, governments would realise that they can benefit politically from a Federal Independent Commission Against Corruption.

After all, such a commission would confirm that the vast bulk of politicians and policy processes are in fact not corrupt.

Likewise, governments should want the processes for developing and publicising its key economic blueprint to be seen to have integrity.

Policy making – in particular economic policy making – is complicated. Specific ideas are hotly contested.

But the more transparency around data, assumptions, and projections, the better our debate and policy outcomes will be.

David Richardson has worked in Canberra policy and political circles for a generation. He is rigorous, hardworking and discreet. Before working at the Australia Institute, he worked for various governments – helping design Budgets from the inside with access to the most sensitive information – even assisting the Expenditure Review Committee. For many years he worked inside an integral part of Australia’s democratic infrastructure: the Parliamentary Library. Confidentiality was key to all these previous roles. So, he was not excluded from the lock-up because he could not be trusted.

He was excluded because the government played favourites.

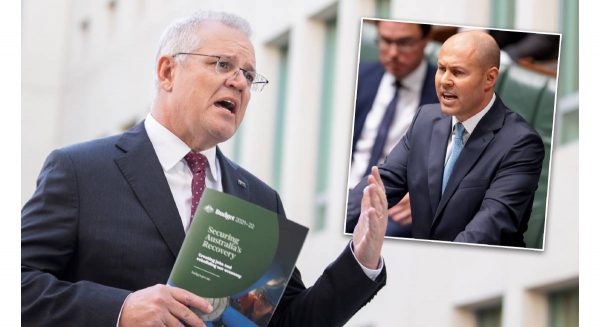

But worse, the government now refuses to even say who it is playing favourites with. The Treasurer refuses to answer simple questions about who was let into the lock-up or how such decisions were made.

Not only were certain people excluded from viewing the nation’s premier economic statement – we are not allowed to know how they got on the government’s blacklist.

One person who made it in to the lock-up last year was economist and commentator Judith Sloan, who boasted: “I can bang out the required 800 or so words in no time at all and have hours to spare – hours to annoy everyone else in the lock-up; hours to hang out in the bathroom reading a novel.”

Impressive – but perhaps her slot could have gone to someone who would spend their time reading the Budget papers, not fiction.Covid has been cited as the reason for the drastically reduced lock-up numbers.

As with many parts of our life, the lock-up should have to (and did) change for the pandemic.

However, the government did not choose the most COVID-safe approach. Last year, the ACT’s Chief Health Officer wrote to Treasury that “a virtual/digital lock-up event … would provide the lowest risk”. It would also have allowed the greatest diversity of organisations and experts to review the Budget papers.

Such a solution, and even the idea of extra rooms, was seemingly beyond Treasury.

Instead, the Treasurer went for a model that limited access and let the government more easily cherry-pick attendees.

David Richardson knows his way around Budget papers and economic forecasts. Perhaps that is what the government does not trust. David’s analysis of previous Budget decisions has of late played an important part in the country’s economic policy discussions.

For example, his detailed work on the flawed economic logic of the coalition government’s proposed big business company tax cuts was part of the reason the Senate rejected the plan.

Politics is a noble calling. It is an essential part of a working democracy. However, when politicians trash processes for short-term, petty political gain they not only trample democracy – they diminish themselves, and ultimately, their own popularity.

David Richardson attending Budget lock-up is not a Covid risk or security threat. If Josh Frydenberg is Treasurer when the next Budget comes around, he should make sure David gets in. It would not just be good for economic policy transparency; it would be good for the Treasurer too.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

5 ways and 63 billion reasons to improve Australia’s tax system

With a federal election just around the corner, new analysis from The Australia Institute reveals 63 billion reasons why our next Parliament should improve the nation’s tax system.

Business groups want the government to overhaul the tax system? Excellent – we have some ideas.

The landslide win by the ALP has seen business groups come out demanding the government listen to their demands despite having provided them no support, and plenty of opposition, over the past 3 years.

10 reasons why Australia does not need company tax cuts

1/ Giving business billions of dollars in tax cuts means starving schools, hospitals and other services. Giving business billions of dollars in tax cuts means billions of dollars less for services like schools and hospitals. If Australia cut company tax from 30% to 25% this would give business about $20 billion in its first year,