Unfinished business for Australia’s corruption watchdog

The National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) is the independent body that detects, investigates and reports on serious or systemic corruption in the Australian Government. Four reforms would increase confidence in the NACC and help it expose corruption.

Allowing public hearings whenever in the public interest

The NACC can only hold public hearings in “exceptional circumstances” and when “it is in the public interest to do so”. The Hon Robert Redlich was the head of the Victorian anti-corruption watchdog, which is also only permitted to hold public hearings in “exceptional circumstances”. Redlich argues there is no need “to require ‘exceptional circumstances’”.

The NACC should instead be allowed to hold public hearings whenever it is in the public interest, regardless of whether the circumstances are exceptional or not. Public hearings would build trust and allow the commission to demonstrate that it is investigating corruption effectively and appropriately. They would also discourage corruption by showing the consequences for such behaviour.

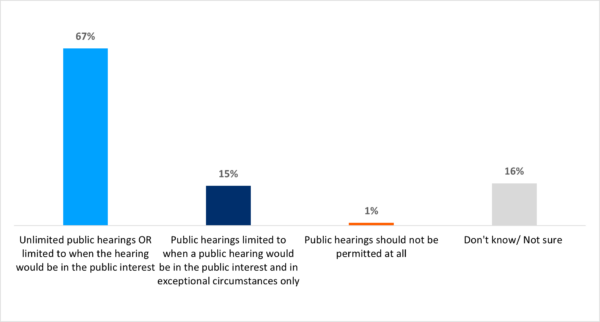

Two in three Australians (67%) agree the NACC should be able to hold public hearings whenever they are in the public interest.

Figure 1: When the NACC should be able to hold public hearings

Implementing a whistleblower protection authority

The NACC can initiate investigations in response to referrals from whistleblowers. Therefore, it is essential that whistleblowers are able to speak up without fear of reprisal. While the NACC includes some protections, more are needed to give whistleblowers the confidence to speak out.

A bipartisan joint parliamentary committee recommended a whistleblower protection authority in 2017, and it was a 2019 election commitment from Labor.5 The original legislation for the

NACC, proposed by independent MPs Cathy McGowan and Helen Haines, also included a whistleblower protection authority, but it was not included in the final legislation the Albanese Government took to Parliament.

The government should set up an independent whistleblower protection authority.

Making the oversight committee balanced

The NACC is overseen by a parliamentary committee. The Government selects the commissioner and deputy commissioner of the NACC, but its choice is approved or rejected by a parliamentary committee. However, because the government has half the committee seats, plus the casting vote of the chair, the same party that selects the commissioner and deputy commissioner has the numbers to approve them even if every other committee member is opposed.

As the NACC is responsible for investigating the government of the day, this could erode public trust in the independence of the NACC’s commissioners.

To ensure that no one party has majority control, the committee should be able to select any member as chair, or the role should rotate between committee members.

Broadening the inspector’s remit

Because the NACC has such broad powers, there is an independent inspector who investigates complaints made about its conduct or activities. The inspector’s powers are focused on ensuring the NACC itself complies with the laws and behaves fairly. The inspector should also oversee the performance of the NACC, including how long its inquiries take and whether its actions align with its objectives.