Why Does the RBA Want More Unemployed Aussies?

By chasing an invisible and moving target, the RBA’s theories on unemployment and inflation could jeopardise the jobs of 140,000 Australians.

Monthly inflation figures show that price increases continue to slow, down from 5.4% for the 12 months to June to 4.9% for the 12 months to July.

This is mounting evidence of how wrong the Reserve Bank is on inflation and unemployment. For the good of the country, they need to change their theories on unemployment and inflation before they push Australia into the recession we didn’t have to have.

The RBA believes in a mythical concept called the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment, also known as the NAIRU.

Despite there being little real-world evidence that the NAIRU even exists, it has been embraced by the RBA for decades.

The theory says that if the economy grows too quickly businesses will eventually run out of unemployed workers to hire in order to make the stuff to meet the increasing demand. Unable to find new workers to expand their output, they will instead put up their prices and/or start offering higher wages to entice workers from other businesses. This will lead to a rapid increase in wages and inflation.

The rate of unemployment where this happens is not zero. This is because unemployed people don’t all live in places where businesses need more workers. Most jobs are in big cities, which are the most expensive places to live. Not an easy feat when you’re trying to survive on the poverty-inducing rates of Jobseeker. The unemployed also don’t necessarily have the skills that businesses are looking for.

The NAIRU is not something that can be directly observed or measured. You can only infer where it might be from what happens to inflation, unemployment, and labour costs. It also has a nasty habit of moving. Essentially an invisible moving target. Not the greatest basis for a policy objective.

The NAIRU, according to the RBA, is currently 4.5%. While the unemployment rate is 3.5%. But wait, that’s below the NAIRU. If the data supported this mythical theory, then we should be seeing a rapidly increasing inflation rate and rapidly increasing wages.

The economic data tells a very different story. It shows that both inflation and wages are not accelerating but are instead slowing. Inflation peaked at the end of last year at 7.8% and as the latest monthly data shows, continues to slow.

The latest measure of wages growth showed wages increasing at 3.6%, down from 3.7%. The wages number is the first slowdown in almost two years, so it is not clear that a new trend has been established. But slowing wages growth doesn’t support the idea that we are below the NAIRU.

It’s annoying when reality ambushes your cute little theory.

If this was just a bunch of academic economists pontificating about how the economy worked, then there wouldn’t be much to worry about. But instead, this is the theory that underpins the setting of interest rates, and they can have terrible, life-changing consequences.

The RBA’s solution to the actual unemployment rate being below the NAIRU is to slow the economy by increasing interest rates and increasing unemployment. This is exactly what the RBA is trying to do. Reduce the number of people in employment in order to increase the unemployment rate up to the NAIRU, which the RBA believes is 4.5%.

I know it sounds like a conspiracy theory: the idea that the RBA would pursue a policy designed to make people lose their jobs.

I know it sounds like a conspiracy theory: the idea that the RBA would pursue a policy designed to make people lose their jobs. But this is exactly what Deputy Governor and soon-to-be Governor of the Reserve Bank, Michele Bullock said in a recent speech.

In her speech, she goes into detail about how they will achieve this:

One of the channels through which higher interest rates work to bring down inflation is by reducing the demand for goods and services and hence overall demand for labour… What this means is that labour market conditions will invariably soften as inflation is contained.

Softer labour market conditions means more unemployed. An extra 140,000 if unemployment is to get to 4.5%.

Let me be very clear. The RBA wants to make 140,000 more people unemployed because they believe that unless this happens inflation and wage increases will not slow. They’re doing this to chase an invisible moving target. All at a time when the economic data is doing the opposite of what they would expect.

This all helps explain why the RBA has been obsessed with the idea that we’re about to see a rapid increase in wages at any moment now. Their flawed theory tells them that low unemployment must be driving higher wages and inflation. But the supposed wages explosion has at best fizzed.

It also helps explain why they are blind to evidence that it is profits driving inflation, not wages. This research is consistent with research by international organisations like the OECD, the IMF, and the European Central Bank.

Some experts have said that slowing wages and inflation mean that the RBA has probably finished increasing interest rates. But this is not assured as long as the RBA believes the unemployment rate remains below the unobservable NAIRU. While ever it is, the ideologically blinkered RBA will keep its finger over the interest rate button.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Another hold likely. So, what was the point of the RBA review?

Will the RBA cut interest rates tomorrow? Probably not. It’s Groundhog Day and they’re locked into repeatedly making to same mistake over and over again. A mistake that the recent RBA review criticised them for making just before the pandemic.

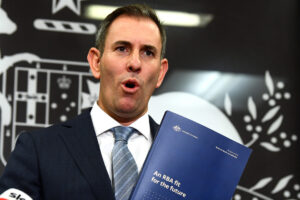

Chalmers is right, the RBA has smashed the economy

In recent weeks the Treasurer Jim Chalmers has been criticised by the opposition and some conservative economists for pointing out that the 13 interest rate increases have slowed Australia’s economy. But the data shows he is right.

In worrying about productivity growth, the RBA has strayed beyond its remit

It’s official: the Reserve Bank of Australia will have its board split in two, and two new appointees will join the reconfigured monetary policy board, whose job it is to make decisions on interest rates. The move was recommended by an independent review panel in 2023. The new members of the monetary policy board, one