While money can’t buy everything, the Australian Government can ‘buy’ a lower Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Indeed, its decision to spend $3.5b on an Energy Relief Fund is an innovative, and likely effective, policy response to current idiosyncratic and challenging economic circumstances.

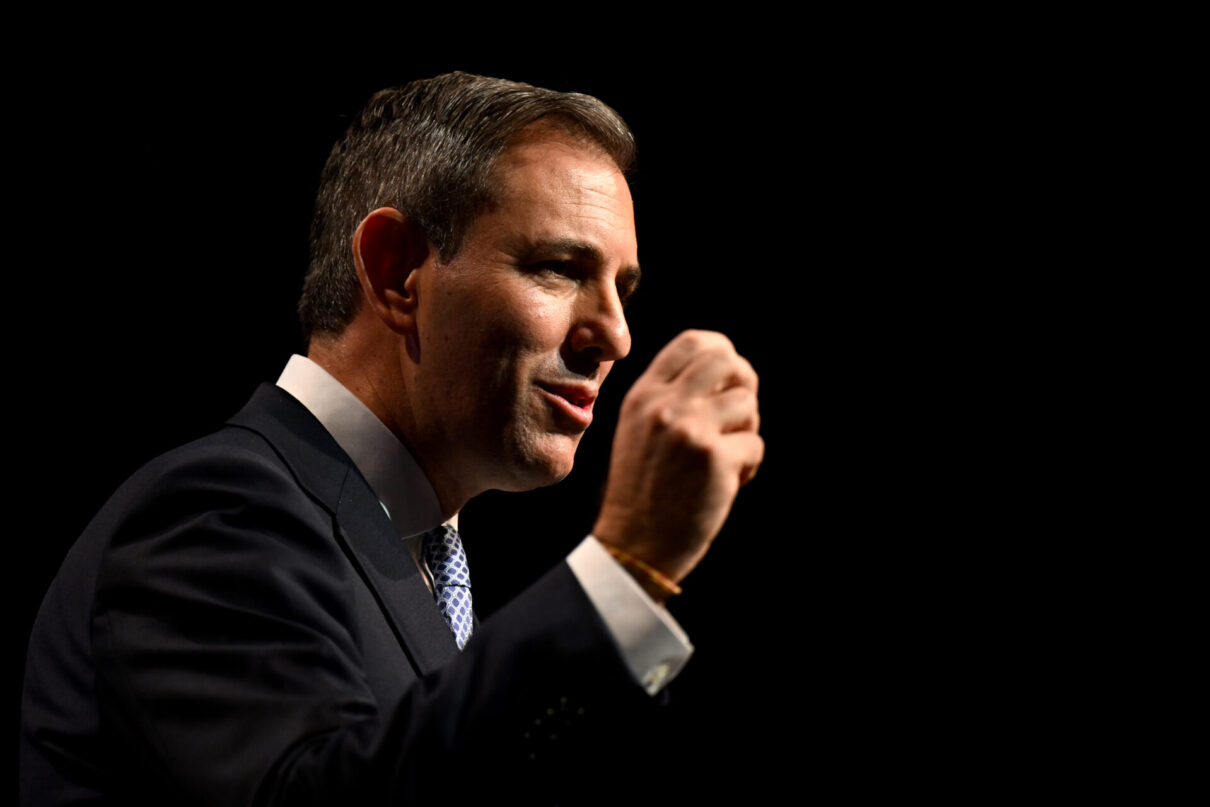

Jim Chalmers’ use of new policy tools to solve new kinds of inflation has enraged many commentators, but the anger of those stuck in the past doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be looking to the future.

For many of the loudest voices in Australia’s economic debate, it is a truism that public spending causes inflation. Public funding is simply fuel for the inflationary fire that they fear more than anything, including recessions and climate change.

For these ‘inflation hawks’ the idea that increasing public spending could lower inflation is simply absurd. But just because powerful people believe something doesn’t make it right.

In Australia, the most common measure of inflation is the CPI.

The CPI represents an incredibly large ‘basket of goods’ that captures the price of pretty much everything a consumer might spend money on.

Of course, it includes the price of bread and milk and petrol. But it also includes the price of building a new house, private health insurance, private school fees and even HECS fees.

Obviously not everyone buys the same things each week and in turn the ABS tries to identify a ‘representative household’. Understandably, that’s not really possible, as most people spend zero dollars per year on private school fees while some spend $100,000 per year keeping their kids away from the masses.

The ABS know that splitting the difference and talking about an average household is a bit silly, so they publish different CPIs for age pensioners and welfare recipients to accompany the ‘headline’ numbers.

So, what’s this got to do with whether Jim Chalmers can ‘buy’ a reduction in inflation or not?

Everything.

If the CPI measures the price consumers pay for things, of course lowering the price of one of those things lowers inflation. If the CPI includes lots of things that most people don’t buy (like new cars), and some things that nearly everyone buys (like electricity), it is possible for the government to literally ‘buy’ a reduction in the CPI by subsidising the price of electricity.

There’s nothing hypothetical about this. When Scott Morison made childcare free during the COVID19 pandemic, it lowered the CPI by 1.1% and made life easier for a lot of people. No one said he was ‘cheating’. Likewise, when Morrison increased the cost of some university degrees, the CPI went up by a 0.25% over two years. The impact on young people, and the indexation of wages and welfare benefits, was very real.

Keeping in mind how sad many people would be if Jim Chalmers proposed a carbon price that caused energy prices and inflation to rise, why are they also sad that he is spending $3.5 billion on lowering electricity prices in order to lower the CPI?

It all comes back to beliefs.

If you believe that inflation is the biggest problem we face, or that inflation is always caused by excessive spending, of course you think public spending will put ‘upward pressure’ on inflation and will gawk at the Treasurer saying he can spend money to buy a lower inflation rate.

But if you believe that the current bout of inflation was caused by a combination of one-off ‘supply shocks’ after Covid, a one-off war in Ukraine that pushed up world energy prices, and a one-off surge in profit grabbing by firms taking advantage of aforementioned supply shocks, then you wouldn’t panic about the Treasurer’s strategy. You’d applaud and wonder why he didn’t go further.

If our current bout of inflation was caused by a succession of unusual events, why would we respond with the usual tool of higher interest rates? Higher interest rates are a great way of getting people with mortgages to spend less in the shops. But if bottlenecks in Chinese factories and high world energy prices caused inflation, and if consumer spending is already falling steadily, why would higher interest rates be the best solution?

People who like paying low taxes like to argue that public spending is neither necessary nor efficient, often because they choose to spend a lot of money on private schools, private health insurance and private transport over public alternatives. And, as luck would have it, those who like low taxes have long argued that low levels of public spending are a great way to control inflation, even though there is little evidence to support it.

Now that Jim Chalmers has argued that subsidising energy is a good way to fight inflation, it is obvious that making childcare, health care and public transport free, as it is in many other rich counties, would be a great way to lower costs of living and tackle inflationary shocks.

That’s not just a scary thought for those who believe public spending is the root of all inflation, it is terrifying for those who hate paying taxes to fund public services that benefit everyone.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

When targeting inflation, the RBA misses more often than it hits

With the fight against high inflation now over, will the Reserve Bank fail to learn the lessons of the past and allow inflation to fall below 2%?

Do you have $3 million in super? Me neither. These changes will actually help you

Labor’s planned reforms to superannuation tax concessions may be being reported as “controversial” but the fact is they are popular.

The continuing irrelevance of minimum wages to future inflation

Minimum and award wages should grow by 5 to 9 per cent this year