Five reasons why young Australians should be pissed off

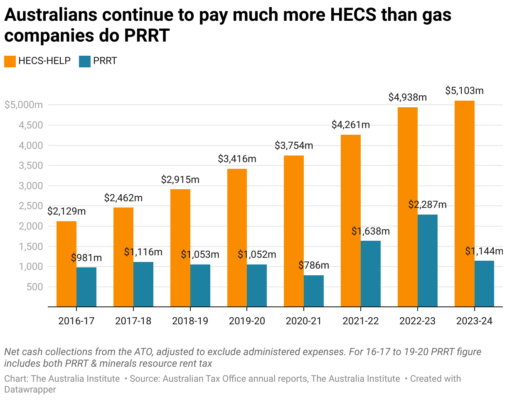

1. Uni graduates pay more in HECS than the gas industry pays in PPRT

University used to be free but is now more expensive than ever. After graduating with an arts degree a young Australian will now repay the government around $50,000.

Meanwhile, Australia is one of the world’s largest gas exporters, but multinational gas corporations pay almost nothing for Australia’s gas. Uni graduates now pay back much more in student debt (HECS/HELP) repayments than the gas industry pays in Petroleum Resource Rent Tax (PRRT). In 2023-24 Australians paid more than 4 times on HECS/HELP than gas companies did on PRRT.

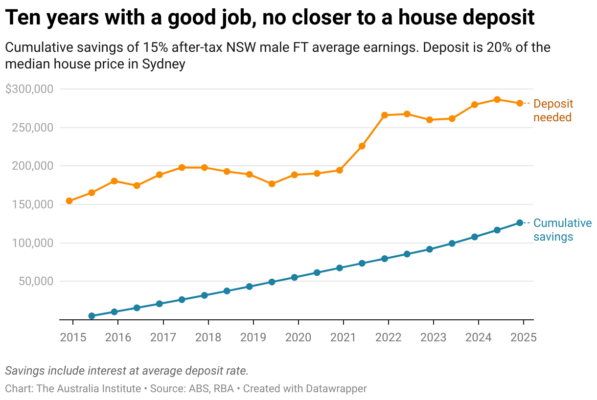

2. It’s almost impossible to save for a house deposit.

House prices are growing quicker than wages, so the amount a deposit costs has grown faster than most young workers can save. Our Chief Economist Greg Jericho has worked out that for most people, if you started saving for a house 10 years ago, you are now further from having a home deposit than when you started.

He found that in 2014, you needed $154,600 for an average Sydney house deposit. By 2024, an average deposit is over $280,000, meaning that even if you managed to save $126,000 over ten years, you need another $155,404!

3. Younger people pay more tax on the same income than older people

The amount of tax you pay is mainly based on your income. But there are a number of ways that older people end up paying less tax on the same amount of income.

The first is that younger people are more likely than older people to have a HECS/HELP debt. This debt is taken out of their pay at the same time as income tax. That is, it comes out before it arrives in their account. While this is technically a repayment of debt and not tax, for the person making the repayment it acts and feels exactly like paying extra tax.

This comes on top of the fact that most older people paid less for their higher education than younger people. This includes people who went to university when it when it was free from 1974 till 1989.

Older people also get more benefit from tax concessions. Tax concessions are tax loopholes that allow taxpayers to pay less than the full rate of tax. The Federal Government gives many Australians tax breaks, also known as tax concessions. Included are details about some tax concessions that are based on age – these are worth $105 billion per year.1 It shows that people 65 years and older get $27 billion, or 25% of these tax concessions. People under the age of 30 get $6.5 billion, or 6% of these tax concessions.

Older people get a much larger benefit from these tax concessions because most of their benefit goes to the rich, and older people are on average more wealthy than younger people. The result of this is that older people are able to use these tax concessions to reduce the tax they pay considerably more than younger people.

4. Young people are forced to buy private health insurance to help make it cheaper for older people to get medical treatment

Private health insurance is directly subsided by the government – it cost the Commonwealth $7.6 billion in 2024-25. But the Commonwealth subsidises private health insurance in another way that benefits older people at the expense of younger people.

If people who earn more than $93,000 per year fail to take out private health insurance, the Commonwealth government charges them the Medicare levy surcharge, which is a higher rate of income tax that costs more than a basic private health insurance policy. The effect is that young people who earn more than $93,000 per year are forced to buy private health insurance.

On average, young people are less likely to actually use private health insurance than older people. This means that private health insurance companies pay out far less on claims for young people, and far more on older people. Without the Medicare levy surcharge many young people would choose not to buy health insurance. Losing these highly profitable younger people would mean that private health insurance companies would need to put up premiums on older people. The younger customers pay for the older ones.

The result is that younger people earning more than $93,000 per year are effectively subsidising older people’s private health insurance.

Even after a young person turns 18 and becomes an adult, legally allowed to vote, drink, smoke, serve on a jury and be deployed to fight in a war, they can still be paid less than other adults.

Australia’s industrial relations system mandates minimum wages across the economy, many of which allow for ‘junior rates’ that mean staff under 21 years old can be paid less than older workers.

Junior rates are often defined as a percentage of the ‘full’ minimum wage. For instance, under the National Minimum Wage, an 18-year-old employee can be paid just two-thirds (68.3%) of what someone aged 21 or over is entitled to. Workers under the age of 18 are also not guaranteed superannuation contributions unless they work 30 hours a week. Almost 9 in 10 workers under the age of 18 (87%) are on junior rates, and about one in three young adult workers (34% of 18-20-year-olds) are on junior rates.

Other countries have moved away from junior rates and towards directly experience-based criteria. For example, in New Zealand, 16- to 19-year-old workers can be paid a ‘starting-out’ minimum wage if they do not yet have six months experience with a single employer. This means that workers are paid according to their ability, not their age. Proponents of junior rates argue that lower pay is necessary to encourage employers to hire younger workers. But over the past decade New Zealand has had broadly similar levels of youth unemployment as Australia, which suggests that junior rates do not lead to higher levels of youth employment.

Power in numbers

This election, Millennials and Gen Z voters will make up 47% of the electorate, which makes them the single largest voting bloc. But young people are being let down by timid governments that are unwilling to make policy changes that would improve their lives. Young people need real action on housing, real action to lower the cost of tertiary education, real taxation reform, and real action on climate change. If Australian governments are unwilling to make these changes, then what incentive do young people have to vote for them?

1 The tax concessions used are superannuation contributions, superannuation earnings, capital gains tax discount, senior and pensioner tax offset, cost of managing tax affairs, franking credits, Medicare levy low-income threshold, individual deductions for gifts and donations, work-related expenses, and tax benefit of rental deductions.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Failing the test: Australian universities in crisis

Great countries have great institutions, but Australian universities are a mess.

Home economics: housing, living standards and the federal election

With housing affordability at an all-time low and the spectre of Trump looming large over our region, Australians’ standard of living will be at the heart of the debate from now until election day.

Why a fossil fuel-free COP could put Australia’s bid over the edge

When the medical world hosts a conference on quitting smoking, they don’t invite Phillip Morris, or British American Tobacco along to help “be part of the solution”.