The Reserve Bank’s decision to keep rates steady reinforced that the economy at this moment remains one with both good and bad signs, and the RBA governor, Michele Bullock, is refreshingly upfront about the difficulties.

Unsurprisingly, the RBA’s call to keep rates unchanged was met by some in the media and conservative commentariat as a failure to be tough. Some would prefer the RBA to be less concerned about the risk of a recession or rising unemployment than getting inflation from 3.6% to below 3%.

Such views are much easier to make when your own job is safe and your income is very comfortable.

It is worth remembering that in the past two years the share of household income spent on mortgage repayments has risen by the amount it did in five years during the mining boom, and by more than occurred in the run-up to the 1990s recession:

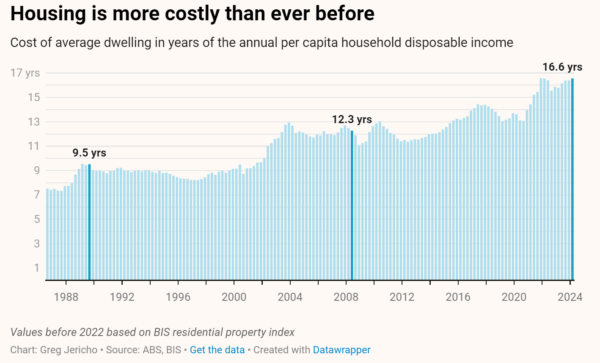

And while we’re not quite spending as great of a share of our income on repayments as we were in 2008, the cost of an average dwelling is now equivalent to 16.6 years’ worth of the average household disposable income, compared to 12.3 years then and 9.5 years in 1989 when the cost of servicing a loan peaked before the recession:

So those wanting more pain are really talking about a historical level of hurt, even though inflation has come down at the same pace it has in other nations with higher rates such as the US and Canada.

Fortunately, Bullock is rather more careful than are those blithely dismissing concerns of a recession.

In her press conference, and the RBA’s policy statement, Bullock noted that the “outlook remains highly uncertain”.

One of the biggest reasons for this uncertainty is something that happened in the latest GDP figures.

The RBA has been trying to work out why household spending was so bad. After all, unemployment was still around 4.0%, wage growth was at 4.1%, and finally real wages were rising.

And yet household spending was utterly stuffed – growing a mere 0.1% over the year in 2023.

Then, in the March GDP data, the Australia Bureau of Statistics revised the figures, in an attempt to get “seasonally adjusted” back to some sort of sense after the years of Covid insanity.

And it now estimates that we spent more in 2023 than previously thought.

Rather than just 0.1% annual growth last year, the ABS now estimates our spending increased by 1.0%.

Now that is still pathetic. As I noted earlier this month, most of the growth was on essential items. The figures in March were just bad rather than terrible.

But the ABS also revised down how much we saved:

The household savings ratio in December was revised down from 3.2% to 1.6%.

In dollar terms the changes look like this:

Household income was not revised by much, so all the changes were about what we were doing with our money – spending more and saving less, or in effect, saving less to spend more.

The question is: what does this mean for inflation and interest rates?

Bullock doesn’t seem to be sure. And she was upfront about this.

She told the media gathering on Tuesday that you can think about these changes “in a couple of ways”.

The first way is the glass half-full view.

People, she suggested, are “saving less to support their consumption because they’re very confident about the future”. That is, we feel confident that our jobs are secure and that our wages will rise above inflation and so why save for a rainy day? Let’s go spend!

The other way is more of a glass half-empty view. In this view she suggested the figures show that “people are really hurting and they’re not saving as much, and they’re really struggling to make ends meet, in which case that doesn’t bode so well for consumption”.

If the glass half-full view is correct, then the coming stage-three tax cuts might add to the amount of spending in a manner that may cause inflation to rise.

If the glass half-empty view is correct, then the stage-three tax cuts will lessen the struggle and have a negligible impact on inflation.

For now, the market continues to believe that the next move is for a rate cut:

But the future here is uncertain and, while the media does like to suggest that uncertainty means a rate rise is more likely, the uncertainty also relates to the possible need for a rate cut.

Bullock noted that the RBA is also focused on unemployment because “people having jobs is critical to them being able to meet the challenges of the higher cost of living”. She also said the bank still believes it is “on the narrow path” to getting inflation down while keeping unemployment low and Australia out of a recession.

But crucially she added that the path “does appear to be getting a bit narrower”.

This certainly is worrying, but it is good to know that the RBA is much more concerned about the great cost of people losing their jobs than are those who blithely suggest rates need to be raised with little to no regard for the risks of a recession or the loss of jobs that would bring.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

How Australia can chart its own course in an uncertain world

The Australian government can’t keep its head in the sand and hope the chaos of the Trump administration will just go away.

Delayed RBA cut is welcome, but borrowers are still lagging

The RBA has cut interest rates – five weeks too late.

Company tax cuts would do little to boost investment and hurt everyday Australians – new analysis

When Treasurer Jim Chalmers brings the nation’s economic leaders together next month, don’t be surprised if big business pushes – yet again – to cut the company tax rate.