LULUCF explained: Why Australia’s emissions aren’t actually going down

Australia’s emissions reduction claims simply don’t add up.

In 2022, the government legislated Australia’s emissions reduction targets, “Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets of a 43% reduction from 2005 levels by 2030 and net zero by 2050.”

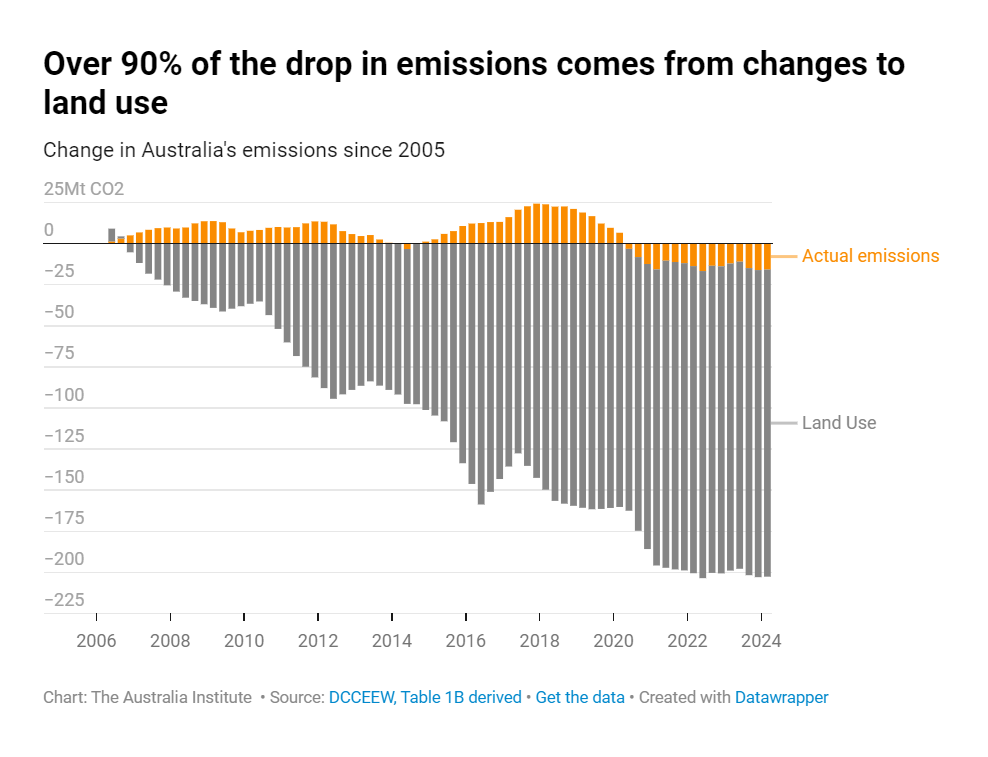

The Australian Government claims that Australia’s domestic emissions have fallen by 29% since 2005.

This claim suggests that Australia is well on its way to meeting its domestic emissions reduction target under the Paris Agreement, even as the Australian Government subsidises and approves fossil fuel expansion.

But Australia is not actually decarbonising its economy and domestic fossil fuel emissions across the economy have changed very little under the Albanese Government (or previous governments).

Industry emissions (including stationary energy, fugitive emissions, and industrial processes) increased by 3% over the year 2023 while transport emissions also increased by 5%.

So how can Australia claim it is decarbonising when it is not?

It all comes down to Australia’s climate accounting.

Australia is a signatory to the Paris Agreement, and under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Australian Government is required to submit a full account of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions to the as part of its international obligations. This ‘inventory’ is a full list of sources (what is released) and sinks (what is absorbed) of greenhouse gas emissions from key sectors; energy (electricity, stationary energy excluding electricity, transport), industrial processes and product use, agriculture, waste and land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF). The government also publishes a quarterly update of these accounts.

When Australia was negotiating the terms of the Kyoto Protocol (the precursor to the Paris Agreement) it lobbied successfully for the inclusion of what became known as the “Australia clause”, which allowed countries to include land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) emissions in their accounting.

The government reports on its progress in meeting these legislated targets through quarterly updates to the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory. It calculates emissions from key sectors; energy (electricity, stationary energy excluding electricity, transport), industrial processes and product use, agriculture, waste and land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF).

The inclusion of the LULUCF sector is critical both because of its scale and the intensity of its emissions; it includes emissions from human-induced land use such as land clearing, crops and grazing and forest management.

The land-use sector can act as a carbon source or carbon sink – if forests are growing, carbon is reduced.

Taking a graph of Australia’s emissions over time, it is clear that Australia is not on the path to meeting its emissions targets. However, counting LULUCF emissions can lead to the mistaken impression that the country is on track with emissions reduction.

Successive Australian Governments have been cooking the books on climate for decades thanks to LULUCF.

That is, the Australian Government can claim that Australia’s ‘net’ greenhouse gas emissions are falling because of the arrangements it negotiated under the Kyoto Protocol to include ‘land sector’ emissions in international emissions accounting and because of subsequent rainfall and drought events that are beyond the control of Australian governments.

The disproportionate effect of LULUCF is apparent when actual emissions have barely changed compared to the 2005 baseline after LULUCF data is removed.

Australia’s land advantage

The years Australia chosen as baseline years to measure emissions reductions progress is very relevant when it comes to Australia’s climate claims.

Australia retrospectively set baseline years under both the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement which the government knew were years of high emissions from land clearing.

By retrospectively choosing baseline years like 1990 and 2005, in the full knowledge that land clearing had fallen after those years due to state government changes to land clearing laws, Australia can claim to have delivered significant emission reductions even though actual emissions from actual economic activity has barely fallen.

Australia has a long history of manipulating greenhouse accounting rules in the land sector to achieve its international mitigation targets.

— Polly Hemming, Director of the Climate and Energy program.

So, when the Australian Government claims that it has reduced emissions by 29% it is critical to consider where these reductions come from, and how the baseline calculations are being changed.

It gets worse

Every year since 2018, the government has revised how much carbon will be stored by the land sector and forestry. The LULUCF sector has been revised the most out of all sectors that contribute to the national account.

At the 2024 Climate Integrity Summit, Bill Hare, CEO of Climate Analytics, spoke on LULUCF accounting and how it is prolonging action on industrial emissions.

…less and less action is needed year after year, not because any action has been undertaken, but because the estimation of the land use sink has changed…we see an underlying increase in emissions for which there are no real policies in place.

Australia Institute analysis estimates that 60% of the government’s calculated improvement in projected emissions from 2022-23 were from lower land use emissions.

While estimates of emissions are naturally subject to some change, as Ketan Joshi writes for Renew Economy,

the process of creating these estimates does not occur in a vacuum: these decisions happen in the deep political context of the pressures of fossil fuel protectionism, government reputation and looming elections.

A disappearing act

Revisions to LULUCF estimates accounted for 26 million tonnes of CO2 removed from Australia’s latest quarterly emissions data. That is equivalent to 6% of Australia’s total emissions (September 2023).

The latest Greenhouse gas emissions figures are out, and Australia is barely reducing emissions at all.

Net zero by 2050 is nowhere near enough, but we are failing even that weak commitment.

We need to stop approving new coal and gas mines and keep emissions in the ground. pic.twitter.com/qhr92S5CmE

— Greg Jericho (@GrogsGamut) May 31, 2024

But what of the future?

Emissions reductions in the land sector are variable, with high uncertainty, and difficult to measure which makes them hard to rely on. Then, of course, there is the very real issue that carbon sequestered in the land sector can easily be released (by bushfire, for example) reversing any mitigation.

If there’s nothing else you also take home from today, it’s carbon sequestration in the form of whatever you use to sequest, whether it’s trees, soil, carbon, or any other concept, it’s transitional because it’s not permanent.

— Mark Wootton, owner of Jigsaw Farms

Temporary biological sequestration cannot be treated as though it mitigates real, lasting emissions from digging up and burning fossil fuels. They’re just not equivalent – even if our carbon accounts pretend otherwise.

A problematic measure

Including LULUCF in Australia’s national greenhouse accounting gives the impression that Australia is on track to meet its emission reduction goals.

Experts have suggested separating LULUCF calculations from national greenhouse accounts to make measuring climate action simpler and more explicit. Separating LULUCF from greenhouse emissions data would also aid in targeting the largest sectors (transport, stationary energy and agriculture) for decarbonisation.

Large one-off reductions in land clearing are in no way evidence of a trend towards the decarbonisation of the Australian economy.

Australia’s emissions accounting, while technically ‘within the rules’ of the UNFCCC framework, is not only morally ambiguous, but it also conceals a lack of real emissions reduction.

Indeed, in May 2021, the Norwegian Ambassador in Canberra stated that his country does not include land sector sequestration in its inventory because it would make it “too easy” to meet reductions targets.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Climate target malpractice. Cooking the books and cooking the planet.

As the Albanese government prepares to announce Australia’s 2035 climate target, pressure is mounting to show greater ambition.

Why a fossil fuel-free COP could put Australia’s bid over the edge

When the medical world hosts a conference on quitting smoking, they don’t invite Phillip Morris, or British American Tobacco along to help “be part of the solution”.

Burning homes and rising premiums: why fossil fuel companies must pay the bill

Another summer, another round of devastation: homes lost, communities evacuated, lives upended.