Right now, final submissions are being made by private health insurers to the government for an increase in insurance premiums next year.

In light of reports, they are seeking increases above 5%, it is worth remembering that private health insurance is a terrible way to deliver good health outcomes.

You can’t say public policy is always worse in America, but aside from how they conduct elections, the one policy the US does worse than anywhere else is healthcare.

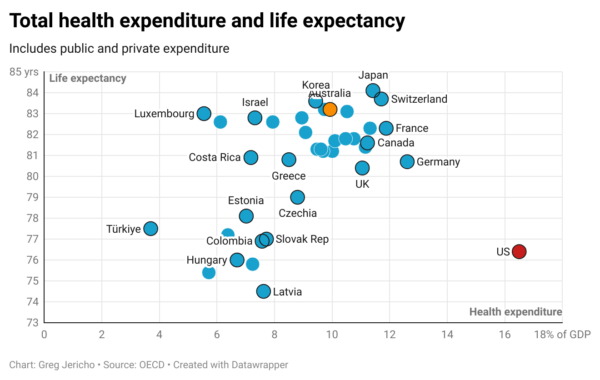

Among OECD nations, the US spends the most on health and as a reward they have one of the worst life expectancies:

There are several reasons why they have this outcome – from structural racism to the serious lack of economic safety nets such as decent minimum wages – but the chief reason is their healthcare overly relies on private insurance in a manner unlike most other nations.

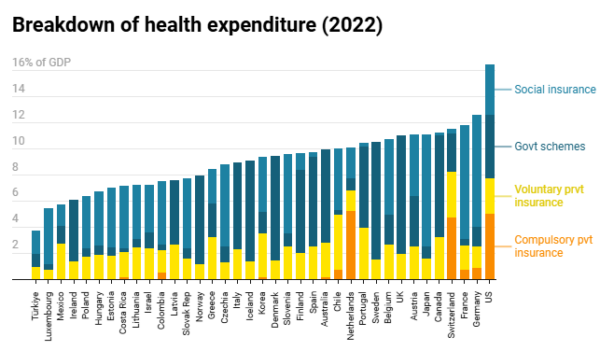

Although the introduction of the Affordable Care Act has shifted some private health insurance from voluntary to compulsory, the nation still massively relies on a system designed to profit from people’s ill heath:

This brings us to the recent reports of private health insurance companies lobbying the Albanese government for premium increases of between 5% and 6% next year.

This increase would be around the long-term average, and as a result would see premiums again rise well ahead of wage growth:

The Australian Financial Review reported that NIB’s CEO has said that the insurer needs an increase of around that mark because “ultimately, we have to cover claims inflation like any insurer because if you don’t eventually you go out of business.”

While this might seem obvious, it ignores the reality that the main reason private health insurers might go out of business is because people hate the product they offer, and even with all the carrots and sticks designed to force people to take out health insurance, a majority of Australians do not want it.

Over six years ago I pondered if private health insurance was a con. In the time since, during which we have experienced the greatest health crisis in a century, nothing has really changed the answer.

Not only does it remain untrue that private health insurance takes stress off the public system, it also remains a fib to call it private – it’s a public system merely carried out in an inefficient manner to deliver a product most people don’t want and haven’t ever wanted.

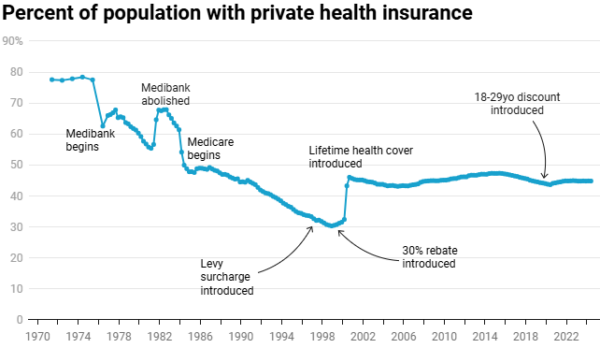

In the late 1990s, after 15 or so years of Medicare, fewer than a third of Australians held private health insurance. Then John Howard decided that the private sector needed help from the public sector.

He introduced a surcharge to penalise higher income earners who did not have private health insurance.

The stick was not enough. Howard then tried the carrot: providing a rebate on your private health insurance. These rebates are quite pricey – the government this year will spend about $7.5bn on them.

It did bugger all – you literally could not pay people to buy it.

Howard returned to the stick and in 2000 effectively forced people to join by 31 years of age with “lifetime health cover” – a program that was accompanied by TV ads showing everyone standing under umbrellas because apparently more people taking out private health insurance made us all better off.

In reality it was just the health insurers who were better off when people decided they should join because they might one day want it when they were older:

Since then, we have had more sticks and carrots – changes to the surcharges and rebates, and then in 2019 even a discount for people aged 18-29.

The result is still fewer than half the population covered by private health.

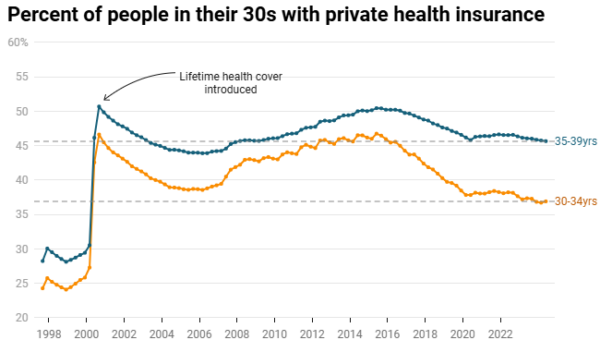

Even more damning on the worth of private health insurance as a product is that the percentage of Australians in their early 30s that have it is now as low as it has been since the introduction of the lifetime health cover:

Perhaps more importantly, those who are “covered” are covered in the sense that a Band-Aid covers a gaping wound.

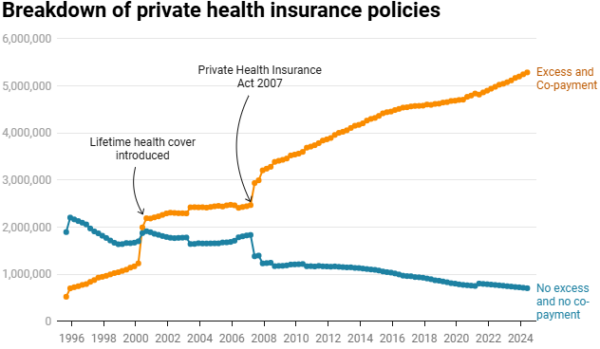

Most people quickly realised that to get within the lifetime health cover frame it was best to take out the minimum possible cover. This resulted in a surge in insurances with excess and co-payments up from about 30% to now 88%:

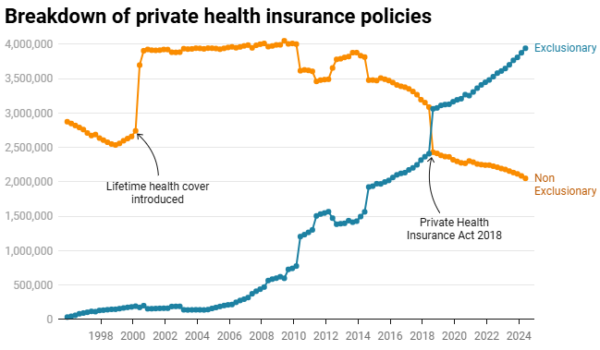

Similarly, whereas once private health covered everything, now the conditions that are insured are more honoured in the exception than the coverage:

This is the main change since I last wrote of the con of private health insurance. In 2018 the Morrison government introduced changes that increased the “maximum voluntary excess levels for products providing individuals an exemption from the Medicare levy surcharge”.

Whereas in 1999, 95% of people had private health insurance with no exclusions, now 65% of policies have exclusions in which various items will not be covered.

So, we have had 25 years of carrots and sticks, all designed to make private health insurance more attractive, and we’ve ended up with fewer people having such insurance and more people not being covered for everything and likely having to pay when they access it.

And all the while the premiums have risen roughly 60% more than wages have.

At some point a health minister might ponder that if people prefer the public health system, then maybe government should just fund it better and stop pretending subsidised private health delivers much other than a dud product that most people don’t want and hate even when they have it.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Private health insurance is for the rich – the rest would rather better public health

ATO figures show that private health insurance is favoured by the rich and it should be subject to GST

Pay a fortune in premiums or risk losing everything – the brutal reality of Australia’s insurance crisis

Struggling families who ditch their home and contents insurance would lose three-quarters of their wealth if their home was destroyed, according to new research by The Australia Institute.

The house always wins: Why we can’t insure our way out of the climate crisis

It is time for the Australian government to admit we can’t insure our way out of the climate crisis our fossil fuel exports do so much to cause.