What would happen in your industry if a judge described someone’s methodology as “inflated”, “lacking evidentiary foundation” and “plainly wrong”?

If your industry would stop using that methodology, then you probably are not an economist and you don’t work for coal companies.

Exactly this happened in 2019 and, with no change and no reflection, the same methodology was cited recently by the NSW Planning Department as it urged the Independent Planning Commission to approve the Mangoola coal mine in the Upper Hunter.

Approving a new coal mine as the world battles climate change and the Upper Hunter endures some of the state’s worst air quality is a bad idea. Doing so while existing coal mines are reducing production and laying off workers is worse still.

But recommending approval of a mine based on economic assessment that not only lost in court, but lost in court against you, is a new level of crazy even for the NSW Planning Department.

The NSW Planning Department’s own economist criticised how the Rocky Hill mine was valued and produced vastly lower estimates of worker and supplier benefits.

Let me explain. In 2017 the NSW Government refused approval of the Rocky Hill mine, proposed for near Gloucester north of the Hunter Valley, following years of community and council opposition.

Rejection of a coal mine by a state government is almost unheard of in Australia and the miners did not want to establish a precedent. But establish a precedent they did, just not the kind they hoped.

The NSW Land and Environment Court also rejected the mine, partly because it would contribute to climate change. The climate aspects of the judgement have made it famous in legal and environmental circles.

Less well known are the parts of the judgement that tackle the ways economic consultants cook the books for their coal mine clients.

Rocky Hill’s economist managed to add $103 million to the value of the mine by assuming that if the mine was rejected, mine workers would work in cafes and other lower-paid jobs, rather than working elsewhere in the Hunter mining industry. Their higher mining wages were assumed to vanish, an approach that the judge described as “contrary to economic theory” and “incorrect”.

Another $182 million was added to the value of Rocky Hill by assuming it would pay higher prices for supplies than it needed to, and assuming many of these supplies would come from NSW rather than being imported.

During an excruciating cross-examination, the mine’s economist was forced to agree that he “hadn’t undertaken any assessment” as to whether or not the estimates on NSW content given to him by his client were accurate.

It was this part that the judge found was “plainly wrong” and that the resulting estimates were “orders of magnitude different” to the estimates that the NSW Planning Department’s economist had made.

Read that again if you have to.

The NSW Planning Department’s own economist criticised how the Rocky Hill mine was valued and produced vastly lower estimates of worker and supplier benefits.

Returning to 2021 and global mining giant Glencore is seeking approval for a large expansion to its Mangoola mine in the Upper Hunter.

The Planning Department has recommended that it be approved due to the economic benefits of the mine, including $108 million in “worker benefits” and $129 million in “supplier benefits”.

These calculations come from the same economist that the department had criticised over the same calculations.

This isn’t a one off. A few week back, the department recommended approval of the Tahmoor mine, south of Sydney, on the basis of the same methodology. When pressed by the Independent Planning Commission, a Planning Department executive said he “guessed there’s different arguments about whether you ought to” include these discredited values.

Different arguments? Perhaps what he means is that there is one argument if a mine is backed by a major corporation and another argument for mines owned by small companies?

No different arguments are acknowledged by the economist who made these estimates. His methodology is unchanged following the Rocky Hill judgement. The only thing to change is his letterhead.

Despite being “plainly wrong”, his firm was bought by Ernst and Young and he was made a partner as part of the deal.

The big question is which of these arguments the Independent Planning Commission will accept.

Will it approve these mines on the basis of their “economic benefits” or follow the Land and Environment Court’s decision that the time for new coal mines is over?

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Should Australia ban fossil fuel advertising?

A tobacco-style ban on fossil fuel advertising would be a decisive win for Australia – and the climate.

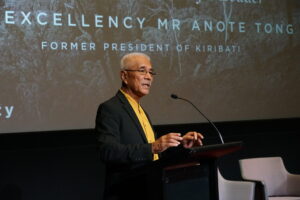

Navigating Australia & the Campaign to End Coal | Anote Tong

Climate change is the greatest moral challenge that humanity has ever had to face, and for those of us who have the capacity to stop it, are we going to do it?

Who knew Queensland’s richest man is a foreign investor?

Clive Palmer’s controversial legal strategies challenge Australia’s trade agreements and environmental laws, and have profound implications for global climate action, writes Stephen Long.