The prime minister’s initial target of beginning the rollout of Covid-19 vaccines “as soon as January” is in tatters and mid-February is looking shaky. Likewise, the target of “fully vaccinating” some 26 million Australians by October. But just because someone fails to hit a target doesn’t mean they shouldn’t have set it. On the contrary, Scott Morrison’s ambitious mid-February vaccine rollout goal means people are working double-time to ensure it doesn’t blow out to March.

Targets play a central role in leading and managing large organisations. They ensure everyone knows which way, and how fast, an organisation is heading. BHP has annual production targets for iron ore, copper, nickel and coal and targets for net zero carbon emissions by 2050 and for a gender-balanced workforce by 2025.

Morrison might not be as good at hitting his targets as BHP, but that doesn’t stop him setting lots of them. His government has targets to deliver surpluses over the business cycle and hold inflation in the 2-3% range. Leaving aside the Covid recession of 2020, the Coalition failed to achieve all its major macroeconomic targets in the six years leading up to the recession as well.

Of course, it’s not just economic targets that Morrison likes to set and forget. There are the targets he has missed for closing the gap in life expectancy and child mortality between Indigenous Australians and the broader community and, of course, the Liberal party’s target of having 50% female representation in parliament by 2025. It’s currently sitting at 25.4%.

Mistakes happen. Events ensue. Priorities change. The longer Morrison waits to set a net zero target, the more expensive it will be for Australian businesses to meet. And if leaders don’t set clear targets it’s harder to hold them accountable for their performance – which is presumably why Morrison has so far refused.

With an election in the offing and the Labor party gripped by internal turmoil, the last thing the prime minister wants to do is remind the Australian public that his junior Coalition partner, the National party, is chock-a-block with coal-loving climate sceptics.

While the differences between Mark Butler and Joel Fitzgibbon on climate policy have been well canvassed, there has been silence around the difference between Barnaby Joyce and Tim Wilson on the same issue. Likewise, the disparity between Dave Sharma and George Christensen. Why did Morrison take months and a press gallery stoush with Tanya Plibersek to rebuke Craig Kelly over his views on vaccines, yet still does not criticise Kelly’s climate change conspiracy theories? That Morrison can’t call out the Liberal member for Hughes without repudiating the majority of the Nationals might have something to do with it.

Morrison’s expensive delay on a 2050 target is all the more absurd as every Australian state and territory has already committed to net zero targets by 2050. If all of the state premiers and chief ministers reach their stated targets then, by definition, Australia will have succeeded without Morrison holding so much as a pen.

Scott Morrison likes to define his role by what he doesn’t do, but only the commonwealth government can negotiate global climate ambition with other countries and sign a treaty on Australia’s behalf. At precisely the time that the Australian defence community is worrying about China’s growing influence in the Pacific, Pacific nations are calling on Australia to show some climate leadership, likewise our European allies. Ignoring the requests of our nearest neighbours is not just short-sighted, it’s dangerous. As Australia is trying to strengthen its trade and diplomatic ties with “anyone but China”, we are souring their requests to rein in our obsession with new coal mines and fracking wells.

Morrison isn’t stupid and neither are those around him. It’s not that he doesn’t care about climate change, it’s just that he cares more about holding the coalition between the Liberals and the Nationals together a little longer. He knows climate change is real, he knows targets are important, and he knows that pretending otherwise costs him some votes and some credibility. But he also knows that, because targets do matter, if he sets a net zero target for Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, he has picked a fight with the Queensland National party that could cost him the next election.

The prime minister likes to say that he won’t set a target for net zero until there is a plan to get there. He doesn’t hold a hose, he doesn’t hold a needle, he doesn’t make the plans and he doesn’t set the targets. But boy does he hold state premiers and the opposition to account. If leaders don’t set targets, it’s impossible for others to make plans – which, is, of course, exactly what Scott Morrison wants.

• Richard Denniss is the chief economist at independent thinktank, the Australia Institute. @RDNS_TAI

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

There is no such thing as a safe seat | Fact sheet

A notable trend in Australian politics has been the decline of the share of the vote won by both major parties at federal elections. One effect of this is that there are no longer any safe seats in Australian politics: minor parties and independents win more “safe” seats than they do “marginal” ones. The declining

Eight things you need to know about the Government’s plan to change Australian elections

And eight ideas to improve it

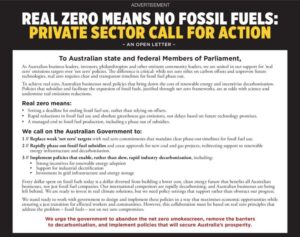

Private sector demands ‘real zero’ policies and an end to fossil fuels

Some of Australia’s best-known and most respected industry, business and community leaders have written an open letter to state and federal MPs calling for an end to the “net zero smokescreen” to “secure Australia’s prosperity”.