The Dimensions of Insecure Work in Australia

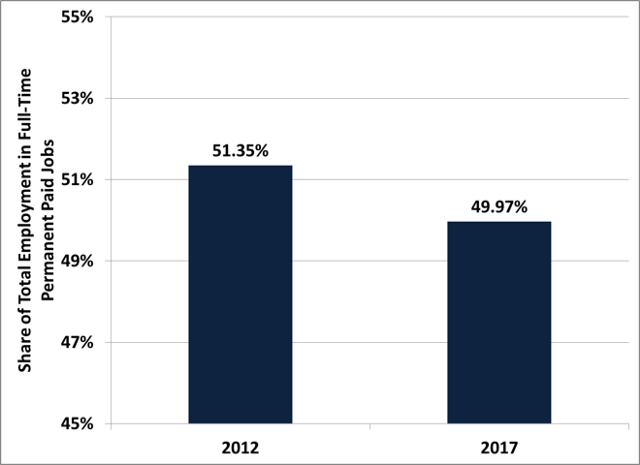

Less than half of employed Australians now hold a “standard” job: that is, a permanent full-time paid job with leave entitlements. That’s the startling finding of a new report on the growing insecurity of work published by the Centre for Future Work.

The report, The Dimensions of Insecure Work: A Factbook, reviews eleven statistical indicators of the growth in employment insecurity over the last five years: including part-time work, short hours, underemployment, casual jobs, marginal self-employment, and jobs paid minimum wages under modern awards.

All these indicators of job stability have declined since 2012, thanks to a combination of weak labour market conditions, aggressive profit strategies by employers, and passivity by labour regulators. Together, these trends have produced a situation where over 50 per cent of Australian workers now experience one or more of these dimensions of insecurity in their jobs - and less than half have access to “standard,” more secure employment.

“Australians are rightly worried about the growing insecurity of work, especially for young people,” said Dr. Jim Stanford, one of the co-authors of the report. “Many young people are giving up hope of finding a permanent full-time job, and if these trends continue, many of them never will.”

The report also documents the low and falling earnings received by workers in insecure jobs. While real wages for those in permanent full-time positions (the best-paid category) have grown, wages for casual workers have declined. And part-time workers in marginal self-employed positions (including so-called “gig” workers) have fared the worst: with real wages falling 26 percent in the last five years.

“Given current labour market conditions and lax labour standards, employers are able to hire workers on a ‘just-in-time’ basis,” Dr. Stanford said. “They employ workers only when and where they are most needed, and then toss them aside. This precariousness imposes enormous risks and costs on workers, their families, and the whole economy.”

Dr. Stanford called on policy-makers to address growing precarity with stronger rules to protect workers in insecure jobs (such as provisions for more stable schedules, and options to transition to permanent from casual work). He also stressed the need for economic policies that target the creation of permanent full-time jobs.

Related research

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

A fair go for temporary workers from the Pacific

On a whistlestop tour of Fiji, Tonga, and Vanuatu in May, Foreign Minister Penny Wong wanted to focus on climate change, security, and aid funding.

If You Thought Employers Were Exploiting Workers With Too Many Insecure Jobs Before The Pandemic, Wait Till You See The Figures Now

Australia paid a big price for the over reliance on insecure jobs prior to the pandemic. But as our economy recovers, insecure jobs account for about two out of every three new positions. In this commentary, originally published on New Matilda, Economist Dan Nahum explains why that’s a very bad thing – especially in front-line, human services roles. In the context of COVID-19, the effects of insecure work in these sectors, in particular, reverberate across the whole community with dangerous and tragic consequences.

Analysis: Will 2025 be a good or bad year for women workers in Australia?

In 2024 we saw some welcome developments for working women, led by government reforms. Benefits from these changes will continue in 2025. However, this year, technological, social and political changes may challenge working women’s economic security and threaten progress towards gender equality at work Here’s our list of five areas we think will impact on