The Coalition government is handing police and intelligence agencies more and more powers and subjecting them to less and less scrutiny. We should all be alert and alarmed.

It’s more than two years since journalist Annika Smethurst broke the story the government was considering draconian new powers to allow the Australian Signals Directorate to spy on Australian citizens for the first time in history and more than one year since the Australian Federal Police all but confirmed the story by raiding Smethurst’s house.

The ASD is supposed to intercept foreign communications and disrupt the activities of overseas criminals and hackers, but soon it will be able to spy on Australian citizens, a move which ought to send a shiver down your spine. Not because you’ve done anything wrong, but because once police and intelligence agencies are granted expanded powers they are rarely rescinded, and because there is a long history of mission creep when it comes to Australia’s anti-terror laws.

Since 9/11, Australia has passed a raft of national security and terrorism laws, including a mass surveillance data retention scheme that has been widely abused and “control orders” ostensibly designed for terrorists but used on bikies. In recent years, the government has very publicly cracked down on whistleblowers, the AFP began raiding the homes and offices of journalists for reporting leaked information – as if that’s not the bread and butter of good journalism – and the Attorney-General consented to the prosecution of not just whistleblowers, but the lawyers representing them as well. Now trials are happening in secret, which should be anathema in a democracy. Things are looking bleak.

Former president of Timor-Leste and Nobel Peace Prize laureate José Ramos-Horta this week told an Australia Institute webinar he was shocked a country like Australia would allow court proceedings to be obscured as in the case of Witness K and Bernard Collaery.

“We don’t read about these secret trials in a country like Australia. I am not surprised when secret trials happen in North Korea, but in Australia that is really mind-boggling,” he said.

The trial – parts of which will be held in secret – relates to the disclosure of information related to an unconscionable act: bugging the room being used by East Timor during negotiations over the rights to oil and gas in the Timor Sea. The operation was not to protect national security, but for oil and gas company profits.

“To spy on Timor-Leste on behalf of Woodside, on behalf of ConocoPhillips, on behalf of oil companies, you know, it’s a bit like you have a poor old lady somewhere in an Australian neighbourhood, 80 years old, poor, living on a meagre pension, and then Australia tries to extract money from that old lady,” Mr Ramos-Horta said.

The expansive powers of police and intelligence agencies are alarming, but the lack of proper oversight is downright frightening.

Australia Institute research released this week showed Australia’s parliamentary oversight of intelligence agencies was the weakest of all the “Five Eyes” countries (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United Kingdom & the United States) that share intelligence. Australia’s oversight committee had limited powers to conduct its own inquiries, did not have jurisdiction over all bodies with intelligence functions and could not review any actual intelligence operations (past, current or planned).

As the surveillance powers of Australian intelligence agencies expand so, too, should scrutiny of their actions. Protections on the civil liberties, human rights and privacy of individual citizens have not kept pace with the remarkable increase in the agencies’ data collection, data interrogation and data cross-referencing capabilities. In a democracy such as Australia and in the absence of a Bill of Rights that explicitly protects things like freedom of speech and freedom of the press, this is the responsibility of the national Parliament. A stronger parliamentary committee to exert greater control over the agencies and ensure greater accountability to Parliament is required to ensure rights of Australian citizens are fully protected.

Proper scrutiny and protection of civil liberties is more important than ever during the pandemic, especially as governments at state and federal level exert their executive power to restrict freedoms of movement and assembly and the right to protest.

But even during normal times, back in the good ol’ days when our biggest problem was just the existential threat of climate change, our integrity and accountability mechanisms had huge gaps the Coalition government promised to close with a Commonwealth Integrity Commission. But two years after it was promised the attorney-general has delivered diddly squat.

This week the National Integrity Committee of former Judges convened by the Australia Institute called on the Morrison government to release draft legislation for a National Integrity Commission. It has been nine months since Attorney-General Christian Porter stated legislation for the proposed Commonwealth Integrity Commission (CIC) would be released “shortly”, and 20 months since the consultation paper for the CIC was first released.

Independent MP Helen Haines, not content to wait, this week tabled a bills package into the House of Representatives to establish an Australian Federal Integrity Commission (AFIC), and other measures to boost integrity in Federal Parliament.

And it is a move the Australian public wants. Our research shows almost nine in 10 Australians support establishing a national anti-corruption watchdog, and furthermore three in four Australians want such a watchdog established this year.

With parliamentary sitting weeks in 2020 running out, the government should help politics help itself, by establishing an anti-corruption watchdog as a matter of urgency. This would help all Australians feel more confident with what is and is not happening in the name of our democracy.

- Ebony Bennett is deputy director at independent think tank The Australia Institute – @ebony_bennett

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

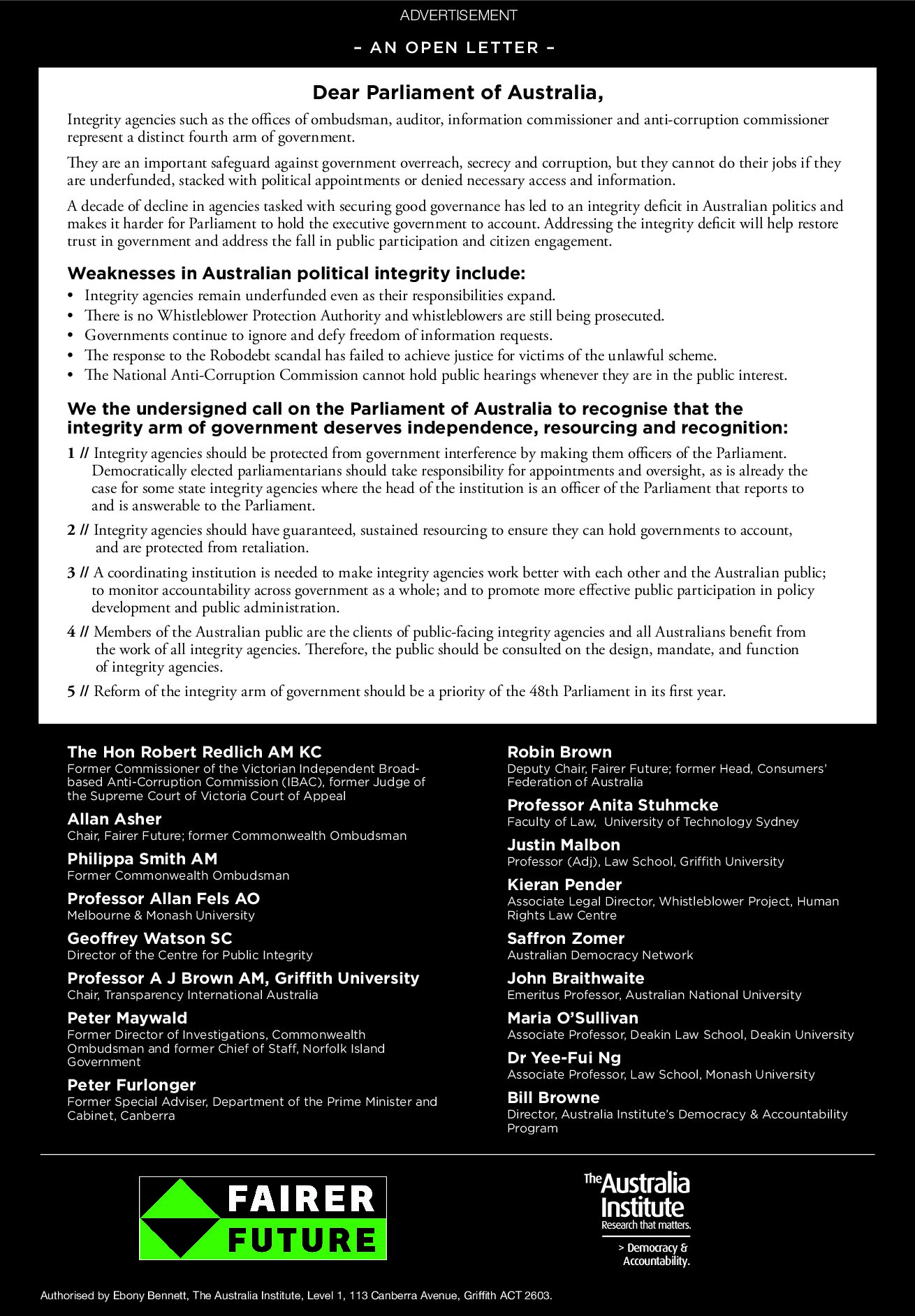

Open letter calls on newly elected Parliament to introduce Whistleblower Protection Authority, sustained funding for integrity agencies to protect from government pressure.

Integrity experts, including former judges, ombudsmen and leading academics, have signed an open letter, coordinated by The Australia Institute and Fairer Future and published today in The Canberra Times, calling on the newly elected Parliament of Australia to address weaknesses in Australian political integrity. The open letter warns that a decade of decline in agencies

Underfunded, toothless and lacking transparency – time for a new era of integrity in Tasmania

As Tasmania’s newly elected politicians jostle to form government, new analysis from The Australia Institute shows that a deal to address integrity would be popular among election-weary voters.

Integrity 2.0 – whatever happened to the fourth arm of government?

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese came to office in 2022 promising a new era of integrity in government.