The 2019-20 taxation statistics released this week by the ATO provide a plethora of data that reveals with precision the salaries of people by location, occupation age and importantly, gender.

The 2019-20 taxation statistics released this week by the ATO provide a plethora of data that reveals with precision the salaries of people by location, occupation age and importantly, gender.

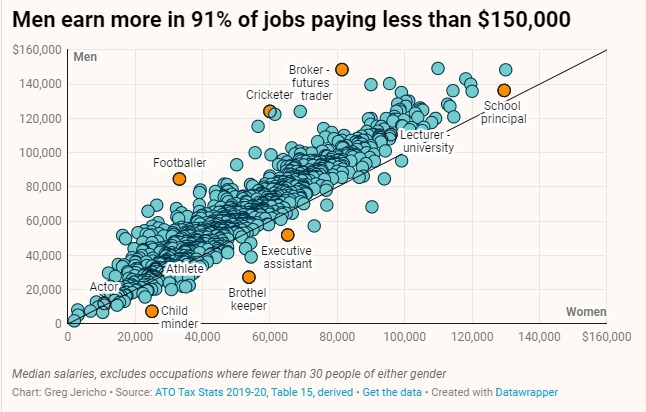

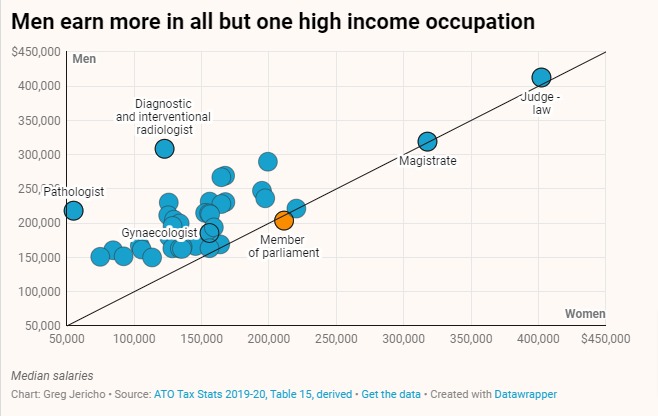

Labour market and fiscal policy director, Greg Jericho, undertook a deep dive into the data. He notes in his column in Guardian Australia that in 91% of over 1,000 separate occupation groups from Nightclub DJ through to Magistrates and Judges, men have a higher median income than do women.

The data reveals that women are less likely to work in higher paying occupations, and perhaps more damning those occupations with high levels of female participation are more likely to be low paid than are jobs which are mostly done by men.

It is clear that work traditionally done by women is much lower paid than stereotypically traditional male jobs.

But it is not just those occupations where the imbalance occurs. Even in jobs where women are the majority of workers, men will likely have a higher median salary and be more likely to be paid over $90,000 a year and be within the top two tax brackets.

Women for example make up 57% of a journalists, and yet account for just 46% of all journalists earnings between $90,000 and $180,000 and a mere 36% of those earning above $180,000.

The data highlights that the gender pay gap is not just about being paid the same hourly rate for the same work, but who gets the opportunity to work more hours, and who is more likely to be given roles that pay higher wages.

It reveals a deep structural issue within our economy in which even in jobs largely done by women, the men in those occupations will most likely be paid more.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Analysis: Will 2025 be a good or bad year for women workers in Australia?

In 2024 we saw some welcome developments for working women, led by government reforms. Benefits from these changes will continue in 2025. However, this year, technological, social and political changes may challenge working women’s economic security and threaten progress towards gender equality at work Here’s our list of five areas we think will impact on

Centre For Future Work to evolve into standalone entity

The Centre for Future Work was established by the Australia Institute in 2016 to conduct and publish progressive economic research on work, employment, and labour markets. Supported by the Australian Union movement, the centre produced cutting edge research and led the national conversation on economic issues facing working people: including the future of jobs, wages

Go Home On Time Day 2025. As full timers disconnect, part timers are doing more unpaid overtime

New research by the Centre for Future Work at The Australia Institute has revealed a disturbing new twist when it comes to unpaid overtime in Australia.