The Safeguard Mechanism’s pro-fossil flaws – explained

Governments work hard to ensure that Australian climate policy seems effective to media and voters, while simultaneously ensuring it does nothing to limit the key thing that is wrecking the climate – fossil fuel expansion.

Which brings us to Labor’s revamped ‘Safeguard Mechanism’.

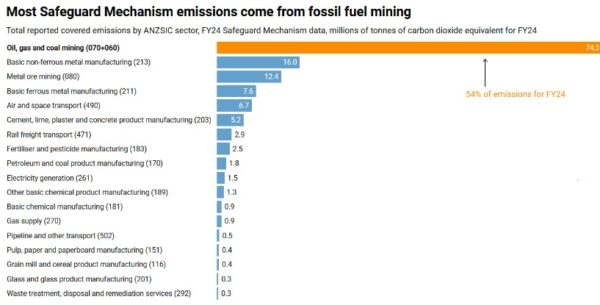

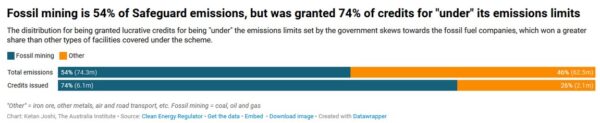

First, let’s set one thing straight. This is basically all about the coal and gas industries. More than 54% of emissions covered by the Safeguard Mechanism come from gas or coal:

This chart shows how big the emissions from the gas and coal industries are compared to other industries covered by the Safeguard Mechanism. Often industries like cement production, agriculture or manufacturing are presented as being a big part of Australia’s climate debate. This chart shows that they’re not, at least in terms of the Safeguard Mechanism.

So, here’s how the Safeguard Mechanism manages to look effective while actually facilitating gas and coal projects.

Each mine or other Safeguard facility is issued a target level of emissions which collectively ratchets downwards over time, by almost 5% per year.

But each facility has a bevy of ways to secure a weak target, and even then, the polluter can meet this target by:

- (a) purchasing carbon offsets,

- (b) purchasing ‘overperformance’ from other emitters, or by

- (c) actually reducing their emissions.

The logic behind this scheme is that the burden of options (a) and (b) becomes so great that companies eventually simply choose option (c) (such as choosing to electrify processes that run on fossil fuels).

Data covering the first year of operation of the Safeguard Mechanism was released a few months ago, and it shows something very important: the unlimited availability of carbon offsets.

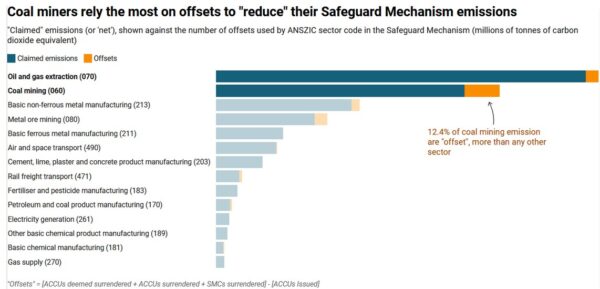

For each of the mines and other facilities covered by the Safeguard Mechanism, they disclose the number of offsets they used to “meet” their designated target without actually reducing their emissions.

The largest users of offsets, by a pretty decent margin, are the coal and gas industries, with the coal mining industry being the most reliant on offsets to adjust its “net” emissions:

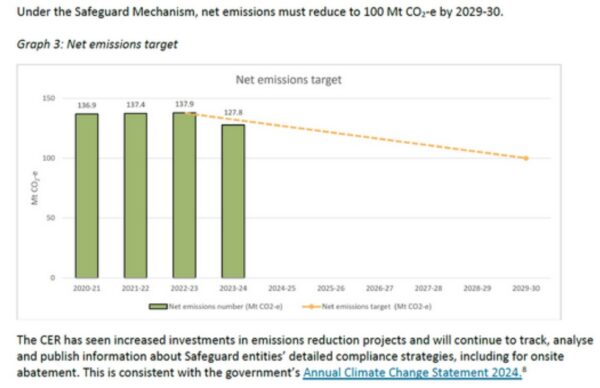

The ‘net’ emissions number (that is, including carbon offsets) is then used by the Clean Energy Regulator to present a graphic that implies the facilities are on track to achieving the overall goals of the scheme:

Perhaps the most worrying revelation in the data is how many fossil fuel extraction facilities were below their target – meaning they were given offsets to sell to others, rather than being forced to buy them to comply.

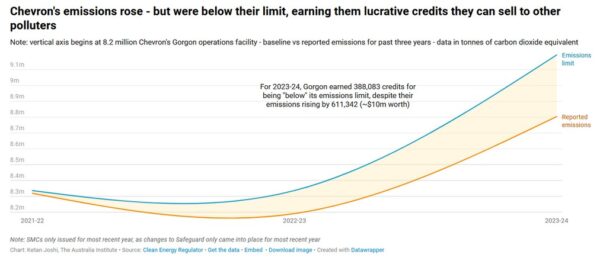

Here’s an eye-opening example. Chevron’s Gorgon facility, one of the highest emitting facilities in the scheme, ended up with an emissions limit (“baseline”) far, far higher than emissions in 2023-24 (the weakest target the project has ever received):

Because Gorgon was under its baseline, it was issued 388,803 ‘safeguard mechanism credits’, which another polluter can buy from Chevron to meet its emissions. This is despite Gorgon’s emissions being the highest they’ve been since FY19.

Not only are high-emitting facilities being issued credits (that they can sell) for being under their baselines, fossil fuel companies in the dataset seemed to be issued a disproportionate amount: those companies are 54% of total emissions, but they earned 74% of all credits issued in FY24. In total, facilities in the fossil fuel extraction sectors earned 6.1 million safeguard mechanism credits.

There is a lot of data to dig into here. But what is extremely clear already is that Australia’s big coal and gas companies are happily already exploiting many of the loopholes in Safeguard – not just to “meet” their targets, but to even actively earn money from the scheme while emissions are going up.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

The Safeguard Mechanism helps gas companies take the piss

The Government’s Safeguard Mechanism is supposed to limit emissions; instead, it just lets companies cheat.

Why a fossil fuel-free COP could put Australia’s bid over the edge

When the medical world hosts a conference on quitting smoking, they don’t invite Phillip Morris, or British American Tobacco along to help “be part of the solution”.

Burning homes and rising premiums: why fossil fuel companies must pay the bill

Another summer, another round of devastation: homes lost, communities evacuated, lives upended.