Weapons of mass obstruction hurt democracy

Be it administrative incompetence, secrecy and trickery, the failure of the Morrison government to hand over Cabinet documents about the Iraq War to the National Archives should trigger serious analysis of how Australia enters conflicts, writes Ebony Bennett.

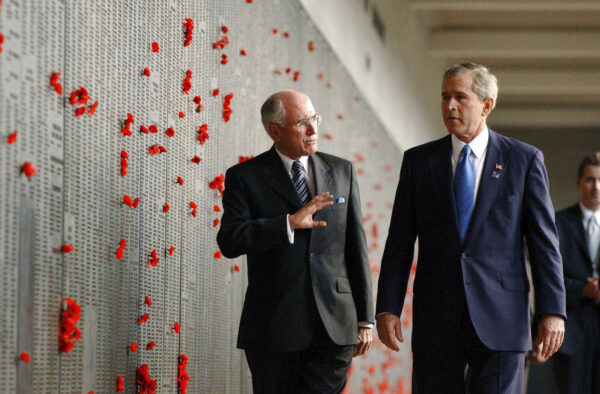

If gun control is one of the best policies in the legacy of the Howard government, the decision to commit Australia to the Iraq war is surely among its worst. Now, twenty years later, the Australian public finds out that the Howard Cabinet decided to take Australia to war based on nothing more than ‘oral reports’ from the Prime Minister.

Given the AUKUS partnership and the very real possibility of another Trump presidency, it is chilling how easily and lightly Australia’s Prime Minister and Cabinet involved this country in armed conflict. The decision to go to war was taken without, it seems, any serious consideration for due process or Australia’s national interest. Without even the most basic analysis and advice from the government’s intelligence, military and policy specialists.

Truth is the first casualty of war and so it has proved to be in the case of the Iraq war, not only in the intelligence failures back then, but now twenty years later in the failure of the Morrison government to hand over all Cabinet documents from that time to the National Archives for publication—administrative incompetence, secrecy and trickery may prove to be the defining legacy of the Morrison government.

Quite properly, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has directed a former departmental secretary and head of ASIO, Dennis Richardson, to investigate how a bundle of Cabinet documents relating to the 2003 decision to commit Australian forces to the war in Iraq could have been overlooked when the relevant documents were provided to the National Archives in 2020.

It is more than likely that Mr Richardson will discover that it was a cock-up, not a conspiracy. Human frailty is not an excuse; even less is stupidity.

As the Prime Minister has made clear, a functioning democracy depends on complete accountability on the part of decision-makers and transparency regarding how decisions were taken. And when those decisions are about spending upwards of $3 billion and putting the lives of Australian defence personnel in danger, it is even more important that the spirit of the Archives Act, as well as its letter, is honoured. There are few Cabinet decisions more consequential than taking the country to war.

The Morrison government should have made certain that it was, the frailty of public servants notwithstanding.

The decision to commit the ADF to Iraq continues to worry many people, as much for whether it was a lawful war as for its perverse consequences — a Middle East that continues to generate misery and suffering for tens of millions of its inhabitants. We now know that there were no Weapons of Mass Destruction — no nukes, no biological weapons and no chemical weapons. But what did we know at the time?

In his 2004 Report, Philip Flood commented that the principal Australian intelligence agencies, along with the rest of the international community, “failed to judge accurately the extent and nature of Iraq’s WMD programmes”. He also noted the divergence between the assessments provided by the two principal intelligence organisations, ONA and DIO. But did Prime Minister Howard know about this? Did the Howard Cabinet? Was there any written briefing available to the decision-makers that might have suggested a measure of caution? Or was a verbal briefing by President Bush enough to justify so momentous a decision? And if so, what does that mean for Australia’s alliance with the US?

These are significant questions, and the public needs to know. And governments need to learn from the mistakes of their predecessors.

The fact that the National Archives release was incomplete because of “administrative oversight” — code for administrative incompetence — will require the further release of relevant documents that may cast additional light on how Australia found itself engaged in what then United Nations Secretary General Kofi Anna described as an illegal war. It also raises a critical question for the Prime Minister: what is he going to do about it?

Tut-tutting will not be good enough. It is high time that the Australian government bit the bullet, as did the UK government with the 2016 Chilcott Inquiry and the US Select Committee on Intelligence in its 2006 Special Report.

The war in Iraq, and the consequential war in Afghanistan, have together cast a dark shadow over Australia’s reputation for ethical international behaviour and preference for diplomacy and dispute resolution over armed conflict on flimsy grounds. The Afghanistan war crimes issues are matters that are yet to proceed through the Office of the Special Investigator and into the criminal courts. But the Iraq war is a different matter, subject to different policy remedies.

The missing documents episode prompts once again a serious consideration by government of the need for a Royal Commission into the intelligence failures that led to the decision to support the US and the UK in waging war for no demonstrable threat remediation or any evident strategic benefit. We need to learn some lessons here.

On any measure, the decision to involve Australia in the Iraq war was wrong and its consequences immense. The death toll in Iraq is estimated to be as high as half a million people, according to at least one academic study. There were no weapons of mass destruction. The legal basis for the war was controversial at best at the time. Australians knew it and hundreds of thousands of citizens took to the streets to protest. Opposition Leader Simon Crean led Labor’s opposition to war. But John Howard knew better. He remains unrepentant and still does not regret the decision, a strategic disaster.

Australia has a sad track record in supporting wars that end badly — Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan. We need to stop doing this. As Albert Einstein allegedly said, insanity is repeating the same actions and expecting different results. Perhaps administrative ineptitude can provide the trigger for some serious analysis of how Australia decides to go to war, and whether we might need to design improved review mechanisms to ensure that decisions to deploy the ADF truly are carefully considered and in the national interest.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

No nukes: Australia must push for serious global nuclear disarmament | Tilman Ruff

Nuclear weapons are still a threat to humanity. In our age of uncertainty, Australia isn’t doing enough to rid the world of these weapons.

As the US chooses destruction over diplomacy in Iran, Australia has to decide between principle and prostration

Australia, like Little Sir Echo, whimpers after the world’s premier bully bombs the ‘bully of the Middle East’.

The stark reality we need to face about guns in Australia

The horrific anti-Semitic terrorist attack in Bondi, the most deadly mass shooting since the Port Arthur massacre thirty years ago, makes gun law reform in Australia necessary. Suggestions from former prime minister John Howard and others that gun law reform is just “a distraction” are cynical in the extreme. Precisely no one is suggesting gun