Why maintaining ambition for 1.5°C is critical | Bill Hare

One of the key things about this whole problem is that the only way to solve it is that we need to rapidly reduce and phase out fossil fuels. That can’t wait a decade. We need to be making substantial reductions this decade.

Bill Hare addressed the Australia Institute’s Climate Integrity Summit on 20 March 2024.

It’s a great pleasure to be in Canberra and it’s been a fantastic day – I’ve learned an enormous amount from all of the speakers today. I just want to go through the one-and-a-half-degree issue; why climate integrity is so important to actually limiting warming to one-and-a-half degrees.

I’m going to start out, as I was asked to, with the state of the global climate.

We know the world is warming. We know from the IPCC assessments that we’re experiencing unprecedented changes, not just global temperature and carbon dioxide concentration – and it’s all due to human activities, primarily the combustion of fossil fuels.

Now, we know also that we’re observing widespread global impacts attributable to climate change. This is very precise language – attributable to – we can actually have a causal chain established quantitatively between the observed climate change and the impacts we’re seeing across nearly all impact domains that you can think of globally.

So we’re already having a big impact and I know it’s also being felt in Australia.

Now we know 2023 was a record year, pretty close to on a one-year average to the one-and-a-half-degree Paris threshold. Depending on the temperature record you believe a very unusual event occurred last year, we don’t fully understand it, but one thing to note is that what we have been seeing in the last year and early this year still lie within our climate model range.

Whether that’s good news or bad news, up to you to judge, but it’s still a bit of a shock that the really extreme temperature levels we’ve seen this year lie within the expected range from our best climate models.

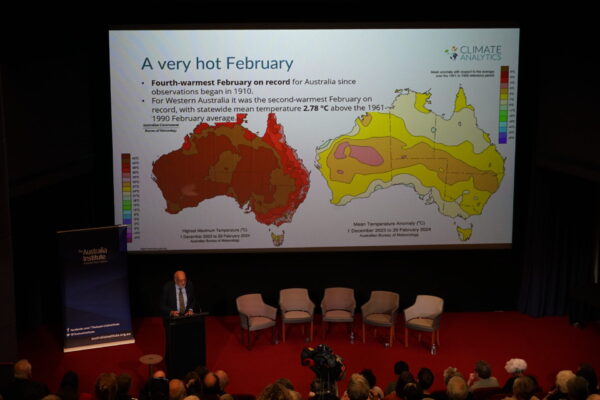

We know here that we’re experiencing all sorts of climate anomalies. Very hot February across Australia. I left Perth yesterday, there’s a big fire north of Perth now with people being told to evacuate. It’s autumn. It shouldn’t be happening. It’s due to global warming.

Why does a 1.5°C limit matter?

The Paris agreement adopted the 1.5°C limit at its COP. Very important elements of this.

Firstly, Article Two specifies that we should hold warming well below two degrees, pursue efforts to limit to 1.5 degrees.

The limit to 1.5 degrees, I think now is the global consensus to get there. In addition, this is where the net zero thing comes from. Article four, call for global emissions to be reduced to in the parliament net zero in the second half of this century. Very important guidance there on what we need to be doing at our countries and globally to get to limit warming to one and a half degrees.

Now, the one and a half degrees limit came from the smaller island states and least developed countries concerned that the IPCC assessment reports were showing too greater damage at two degrees and that led to the one-and-a-half-degree limit being adopted.

Why is it important? I’m just going to give two examples. Coral reefs and deadly heat.

Why coral reefs? Because the Great Barrier Reef now is in the middle of what looks like the worst ever bleaching episode. The whole reef from top to bottom appears to be bleaching. We know that the only way that these reefs, our Great Barrier Reef and others have a chance, is if we can hold warming as close as possible to 1.5°C. By the time you get to two degrees warming, you can forget it.

Even at 1.5°C warming, it’s going to be a very lucky period of time if we see much of our reef survive.

Now, this coral bleaching that we’re seeing now is actually something that’s predicted a long time ago. No government politician who’s been briefed by the scientific community in this country for the last generation can say they didn’t know this was coming. It reinforces the point that Dennis was making this morning.

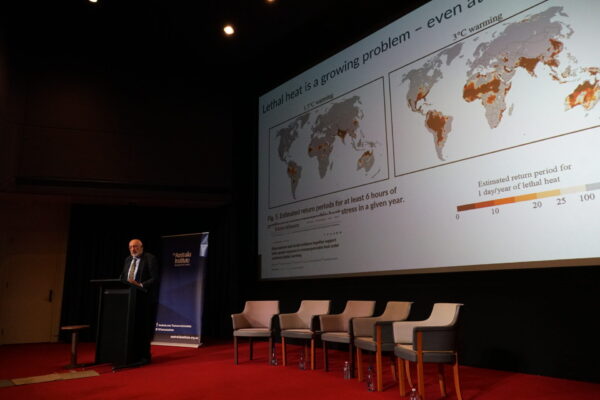

Another problem here – lethal heat. Global warming is hot, but we know that the emergence of lethal heat, the combination of high temperatures with high humidity is leading to a very, very serious risk to human habitability in a number of regions. This risk escalates quickly with warming.

This is a recent paper, one of many in this field in the last years. Left hand side is a 1.5°C warming threshold. Look at the black and dark red areas. Much of South Asia could be subject to non-compensable human heat stress by the time you get to 1.5°C. That means people will not be able to work outside or even live for very long.

Look at our Northern Australia, also under that 1.5°C threshold, we’ve got really severe risk there.

By the time you get to three degrees, I wouldn’t want to say you can forget it, but we’ve got 4 or 5 billion people covered by areas under extreme risk to human health. So that’s one of the risks coming. That’s one of the reasons why 1.5°C is so important – it’s not safe, but it’s about as safe as we’re going to keep this problem, I think.

Now the Paris Agreement 1.5°C agreement is still within reach.

I know there’s a lot of talk in Australia that it’s busted, it’s gone, from NGOs, from scientists and so on.

It’s simply not true.

If we can get emissions done fast enough, then we’ve still got a very good chance of limiting warming to close to 1.5°C. This is the message that’s come from the IPCC and also for more recent assessments.

The one-and-a-half-degree loss story is out there a lot, but as the executive director of the International Energy Agency keeps saying, giving up on the 1.5°C limit only gives something to the carbon industry, the fossil fuel industry, it doesn’t help anyone else. It demotivates governments. It provides excuses for governments not to do the right thing.

Where do we stand on climate action?

Obviously not well, you all know that. Where I’m involved with the Climate Action Tracker, we started that – to sum up a long story short – at Bangkok in 2009, it’s gone on to greater things. But we every year calculate just where global policies are putting us.

Two point seven degrees of warming is where present targets and policies are roughly heading us – in round terms close to three degrees. So we’re a long way from the one-and-a-half-degree limit.

If actually we got all of the net zero pledges that have been made, actually implemented, then you probably get down to close to or a bit below two degrees. So that’s an optimistic spin on it.

The Paris Agreement actually is beginning to work. This is a figure that we regularly update with the Climate Action Tracker showing the changes in the estimated outcome, globally, for temperature from the promises that countries put forward, their targets and from their policies. And you can see since the Paris agreement was adopted and apart from a bit of a glitch around the Trump years, the trend was downwards. But in the last year or so, this has flattened off.

So, in other words, we’re seeing a slowing of progress which was already too slow.

I think this is a political context we’re finding ourselves in now, is that we’re seeing a lot of pushback on climate policy in a lot of places around the world, including in Australia.

One of the key things about this whole problem is that the only way to solve it is that we need to rapidly reduce and phase out fossil fuels. That can’t wait a decade. We need to be making substantial reductions this decade.

We need to essentially be reducing to 40 or 50 per cent below present levels by 2030 to have any reasonable chance of limiting warming to one and a half degrees. Now, if this seems completely mad, remember that the IPCC has shown how this can be done and how it will produce benefits to nearly everyone on the planet through reduced air pollution, reduced energy costs, and avoided climate damages.

So it can be done. It can be achieved.

Now the other fact going on out there is that fossil fuel production plans remain high.

Every year or two there’s a gap report, a fossil fuel production gap report, which attempts to map fossil fuel production plans from a whole lot of countries, add them up and say, how does that compare to the fossil fuel production envelope consistent with one and a half degrees?

This is from the most recent report from last year. We won’t be doing one this year, there’ll be one next year. But it shows, the red line shows the massive gap between the production plans that countries have on the books versus the lowest pathway here, the one-and-a-half-degree pathway.

So this is simply out of control in a way, and Australia is part of that.

Now turning now to Australia, how is it tracking? I could say politely not doing very well. Polly Hemming said that’s a bit polite, but there you go, I said it, and on our climate action tracker rating system, it’s read as insufficient. Its policies do not get towards the one-and-a-half-degree pathway, its target is sort of close to a two-degree pathway, but still a long way from 1.5°C.

As someone acknowledged this morning, its contribution to climate finance is critically insufficient. It’s not good. And part of the Paris deal is that developed countries need to take action, but they also must provide resources to the poorer countries in the world in order for us to solve this problem. Australia has not stacked up there and instead seems to be focused on subsidising its friends in the fossil fuel industry.

The climate action tracker agenda for Australia, looking at our most recent report is that we need to decrease reliance on offsetting and land exchange and forestry in this country. Bit more details in that in a minute. We need to stop supporting the fossil fuel industry, accelerate the phase out of fossil fuel power generation. That is beginning to happen, but it is a bit slow for what we need to be doing to get onto one and a half degrees and a bunch of other policies, which I’m sure you all know about here in the transport sector and so on.

Now, land use emissions in Australia, the so-called LULU CF sector for the nerds here, land use change, land use change and forestry, is a big thing.

Not because it does anything, but because it seems to be a real cottage industry in government to recalculate the land use change in forestry sequestration every year. And what this figure, it’s a bit complicated, shows is that every year since about 2018, the government has recalculated how much carbon is being sequestered in our forests.

The actual basis for this is not very clear to anyone, if it is to the government they’ve never explained it, but the result is that the actual amount of emission reductions Australia needs to get to a target in 2030 keeps reducing year after year. So that means that less and less action is needed year after year, not because any action has been undertaken, but because the estimation of the land use sink has changed.

Yep.

Now Australian emission trends, if you look at the national figures, the government likes to talk to them, look good. The top red line on the left, you can see emissions going down – great. Well actually it’s not so great. The reason why is the land use change issue I just mentioned below, which is the bottom curve on the left-hand side, which shows an increasing sink. Now, if you take out the land use change and forestry sector, look at the left-hand side, the right-hand side, I mean, and you see the top curve is Australia’s emissions excluding land use change and forestry roughly flat if not in the last year, slight of a twitch up. If you take out the other sector that’s actually reducing emissions, the only other sector which is the power sector, then the trend continues slightly upwards, and it has for several years.

So the underlying trend there is not good because we’re not tackling stationary emissions from the mining sector and so on. We’re not tackling transport or agriculture. So, we see an underlying increase in emissions for which there are no real policies in place.

Now the industrial emissions in Australia, that is mining, mineral processing, manufacturing are really significant, but the government is focused on offsets, which does not support a phase out of fossil fuels or emissions.

Offsets do not work

Now, last year we published a report on why offsets don’t work, and I just wanted to step through some of the reasoning there. The majority of land sector offsets actually fail to deliver real genuine additional emission reductions. There’s been numerous papers published in Australia on this, including by Andrew Macintosh and others, which show this.

Much of the sequestered carbon claimed in these crediting systems, the Australian carbon credit system, would’ve happened without the money provided by the offsetting system.

In other words, it’s not additional.

And there are a range of issues that I’m sure you’re familiar with that point to the fact that basically this system does not work to actually offset a tonne of fossil CO2 emissions. Another factor to bear in mind is that most land sector sequestered carbon will ultimately end up back in the atmosphere.

There’s no free lunch in the carbon cycle. Terrestrial carbon storage is there only for a finite period of time. So in the end, if you do the numbers properly, I think Miko Kirschbaum from the ANU was the first to show this over 20 years ago that if you’re offsetting a tonne of fossil CO2 emissions with a temporary land sector offset unit, you’ll end up worse off in the atmosphere than if you’d done nothing in the first place. So it loads the system up for a lot more change in the future.

Within the Australian context, there’s a very special thing going on here that the safeguard mechanism system and its use of offsets enables more fossil CO2 emissions. And you can calculate this.

You can say what if the LNG industry buys an ACCU, one tonne of ACCU, what is the consequential allowed emissions? It’s about 8.4 tonnes. There’s a range, but it shows that actually it’s levering more fossil fuel emissions.

Australia has no policies to phase out oil and gas production.

This is a figure from the Climate Action Tracker update on how countries are tracking on the fossil fuel phase out. Australia registers pretty solidly on the wrong side of the balance sheet. I won’t go through all the elements there. There’s simply not a good message here.

Now, climate integrity actually matters a lot for getting to 1.5°C. As noted earlier, there is a very big number of countries now that have put forward net zero targets, but what we’re increasingly seeing is that buyers of our commodities want to see real zero emission supply chains. So a battery manufacturer making lithium batteries wants to see ultimately real zero lithium and so on. So that is a big pressure on our manufacturing and mining sector here.

Now, our offset system at present to me seems to design to undermine real action rather than contribute to actually limiting warming to one and a half degrees.

And I would contend that the offsets appear likely to undermine ambition to be a renewable energy superpower, then support it, because they’re a distraction from companies actually taking enough action to reduce emissions.

Phasing out offsetting, to me, then becomes a critical agenda item for climate integrity in Australia. If we continue to use offsets, then it looks to me like we will be continuing to enable more fossil fuel production and we will be avoiding the investments in the renewable systems we need to create in order to make ourselves into a superpower.

Final point here is it just occurs to me that our offsetting system looks like the world’s first state sponsored greenwashing system.

I think it’s a really serious issue.

So anyway, I just wanted to clear with this slide because I had all my old friends here, in Neil and so on, from Tuvalu, who helped to get this one-and-a-half-degree target into the Paris Agreement in order to give their countries the best possible chance.

Thanks.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Highlights from the Climate Integrity Summit 2024

2023 has shown us a planet on the brink of collapse. Cyclones, heatwaves, catastrophic floods, fires and landslides have killed people, destroyed ecosystems and decimated communities. And yet Australia is still yet to repair all the homes lost in the Black Summer bushfires of 2020 or the devastating Lismore floods of 2017 and 2022. No

Australia’s compromised climate negotiators

Sitting in a bar in Manhattan recently, there for Climate Week NYC and the United Nations Climate Ambition Summit, I watched as Australians from both government and the private sector worked the room.

New research shows our 2030 emission targets are woefully out of date

The evidence is clear – our current policies and targets are insufficient to prevent dangerous global warming, and not aligned with latest scientific research.