Why You’re Paying More Tax Even Though Real Wages Are Shrinking

It’s a bitter irony.

Wages in Australia are going backwards compared to prices, as surging inflation and mortgage payments gobble up peoples’ pay.

Yet workers of modest means are paying a far bigger slice of their earnings in tax – an extraordinary situation with no precedent in recent times.

It’s contributing to the serious financial pain being felt in lot of households. Unless it’s addressed, it could be politically toxic for the federal government.

It’s already driving a wave of disillusionment among voters watching their tax bills rise while their living standards fall.

So how did we get here?

In short, a combination of bracket creep and the unfortunately timed withdrawal of a tax break that benefited up to 10 million Australians.

For most people, real wages are going backwards as inflation erodes the value of their incomes – but when it comes to tax, that counts for nothing.

Nominal wages determine how much tax you pay, and nominal wages have been rising at a rapid clip.

Over the past year, on the ABS Wage Price Index, wages growth has had a “4” in front of it – something rarely seen.

In the September quarter, wages grew at the fastest pace recorded. Annually, wages posted their biggest rise since 2009.

That’s driving peoples’ earnings into higher tax brackets, even though their pay can’t keep up with the cost of living.

The withdrawal of the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset, or LMITO, adds insult to injury.

Sometimes dubbed the “Lamington”, the LMITO certainly provided some sweet relief for many.

Introduced in 2018-19, LMITO was only intended to be a temporary measure, but it stayed in place until last year.

People on taxable incomes between $37,000 and $126,000 gained tax relief from the measure, but those earning between $48 thousand and $90 thousand a year were the biggest winners – eligible for a tax offset of $1080 after they submitted their annual tax returns, rising to $1500 dollars in the year to 30th June 2022. Now that’s gone.

So, how much has the increase in taxation and the decrease in real wages affected workers?

Inflation really started to take off in the second half of 2021. From September 2021 to September 2023 prices, measured by the Consumer Price Index, increased by 13%, but wages, measured by the Wage Price Index, only rose by 7.4%.

That’s a huge erosion in the real value of peoples’ incomes.

To work out what it means for the bottom line, we crunched the numbers for three, representative income-earners: a low wage earner on $45,000 per year; someone on a middling income of $65,000 a year; and someone on $90,000.

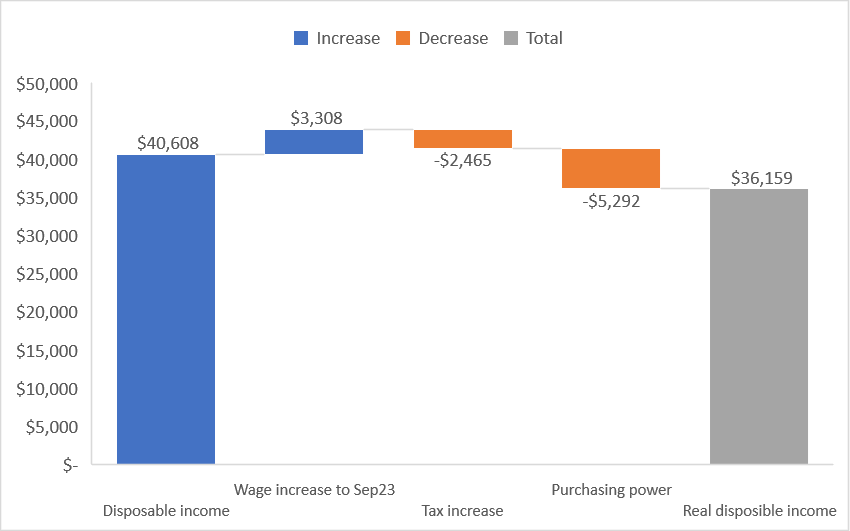

The low-wage worker

If their income rose in line with the Wage Price Index, the pay of our worker earning $45,000 would have gone up by $3,308 over the two years to September 2023. But they’d be paying nearly $2500 more in tax as a result of bracket creep and the loss of LMITO, leaving them just $843 better off.

That goes nowhere near compensating for the increased cost of living.

Let’s assume they spend just about all their disposable income – which is not unusual for someone earning this much money. They’d need to get almost $5,300 more after tax to afford what they used to be able to buy, not the $843 extra they’re getting. In effect, they are almost $4,500 worse off.

The figures are set out in this graph.

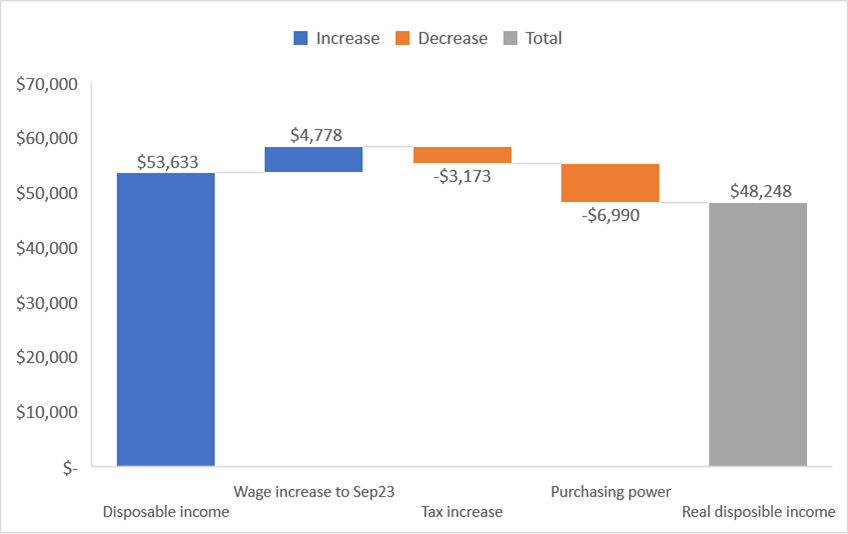

Median wage worker

Now take someone earning $65,000 – about the median wage – in September 2021.

Assuming pay rises in line with the Wage Price Index, their income goes up by nearly $4,800.

But after bracket creep and the loss of LMITO they are paying more than $3100 extra in tax – so their disposable income is only about $1600 higher.

Because of inflation, they’d need close to $7000 more to buy what could have two years earlier.

In effect, they’re worse off by nearly $5400.

That’s more than the average household spends in a year on filling up the tank in their cars.

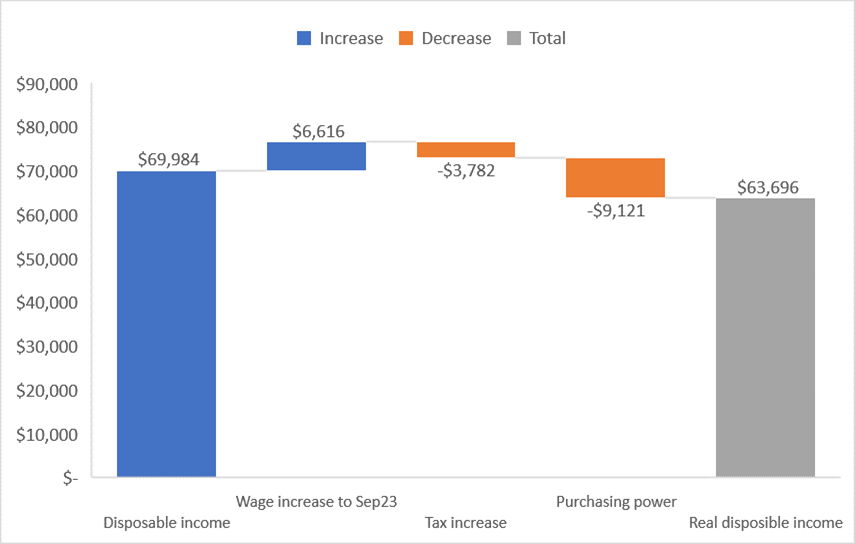

Higher income earner

Assuming pay rises in line with the Wage Price Index, someone on $90,000 in September 2021 would be on earning $6,600 more in September 2023.

But they’re paying nearly $3800 more in tax. So, their after-tax income is only up by just over $2800.

Again, inflation has eroded the value of their money in real terms by more than $9000. if we assume they spend all their disposable income (a less safe assumption for someone on this wage), they’re more than $6200 a year worse off.

Since two income households are the norm, there would be plenty experiencing a double-whammy – where both earners lose the tax offset and lose income to bracket creep, while their real incomes shrink.

Keep in mind that we’re only considering the way earnings have been eroded by tax and consumer price rises – not the massive rises in the cost of servicing mortgages, as the RBA hikes rates to try to curb inflation.

The central bank’s line is that households are “resilient”.

It reckons most have been able to cope with the combination of price rises and the mortgage burden by cutting discretionary spending, picking up extra hours, or moving to better paid jobs.

Yet according to its own numbers, about one in 20 households with a variable rate mortgage don’t earn enough to pay their home loan repayments and essential expenses.

We’re not talking luxuries here – just the basics. Food, clothing, healthcare and utility bills.

Some managed to get ahead on their mortgage repayments before the rate hikes and can draw on this buffer, at least for a while.

But about one in fifty face a choice between paying the mortgage, eating or keeping the lights on.

The RBA analysed nearly 2 million mortgages and divided up owner occupiers with variable rates loans based on household income.

Among home buyers in the bottom 25 per cent, 13 in every hundred don’t have enough money to meet the mortgage and pay for their basic needs.

Close to half are paying more than 30 per cent of their gross income to service the loan – a traditional measure of financial stress.

For many renters, it’s worse.

No doubt the pay day lenders are doing good business.

So far, the government is resisting calls to remodel the Stage 3 tax cuts to provide more relief to people on middle incomes – not the high income earners who stand to gain most from a plan the Coalition devised and Labor inherited.

The Australia Institute has outlined four ways the tax cuts could be reformed.

For people struggling under the burden of higher taxation, falling real wages, and the inflated cost of living, it can’t come soon enough.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

The Wage Price Index shows pay packets are up. So why doesn’t it feel that way?

The latest figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics show wages are growing at a reasonable rate, but a deeper look shows a big problem might be about to bite Australian workers.

If business groups had their way, workers on the minimum wage would now be $160 a week worse off

Had the Fair Work Commission taken the advice of business groups, Australia lowest paid would now earn $160 less a week.

Five reasons why young Australians should be pissed off

1. Uni graduates pay more in HECS than the gas industry pays in PPRT University used to be free but is now more expensive than ever. After graduating with an arts degree a young Australian will now repay the government around $50,000. Meanwhile, Australia is one of the world’s largest gas exporters, but multinational gas