Women still underrepresented in Australian parliaments

The Australia Institute has crunched the data on women’s representation in Australian parliaments.

For more recent figures, see Gender parity closer after federal election

Australian women were among the first in the world to win the vote, with South Australia introducing women’s suffrage in 1894. Women across the continent were eligible to vote in federal elections from 1902 – with the notable exception of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Women stood for election in 1903, but it took over 40 years before women were elected to federal Parliament: Enid Lyons MP and Senator Dorothy Tangney in 1943. In the eighty years since, thousands of women have run for election and hundreds have been elected – so how has the representation of women fared in Australian parliaments?

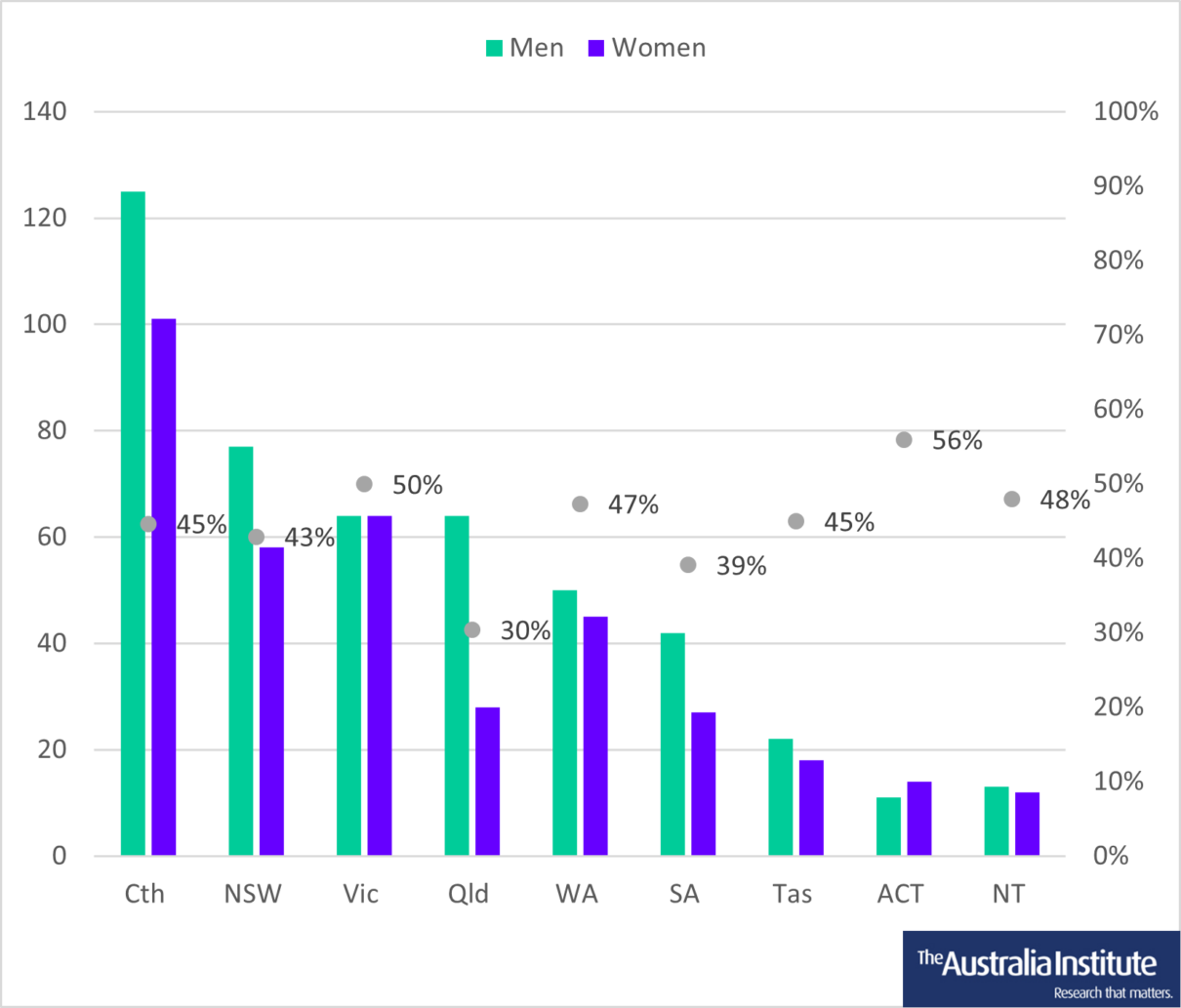

Women are underrepresented in seven of Australia’s nine parliaments. Only in the ACT are there more women than men: 14 to 11. Victoria has exact gender parity, with 64 men and 64 women. In the Queensland Parliament, women are outnumbered more than two to one.

Figure 1: Women in Australian parliaments (as of January 2024)

Research from the Australia Institute finds that the Australian Senate, which allocates seats proportionally to votes received, has been responsible for many milestones for women.

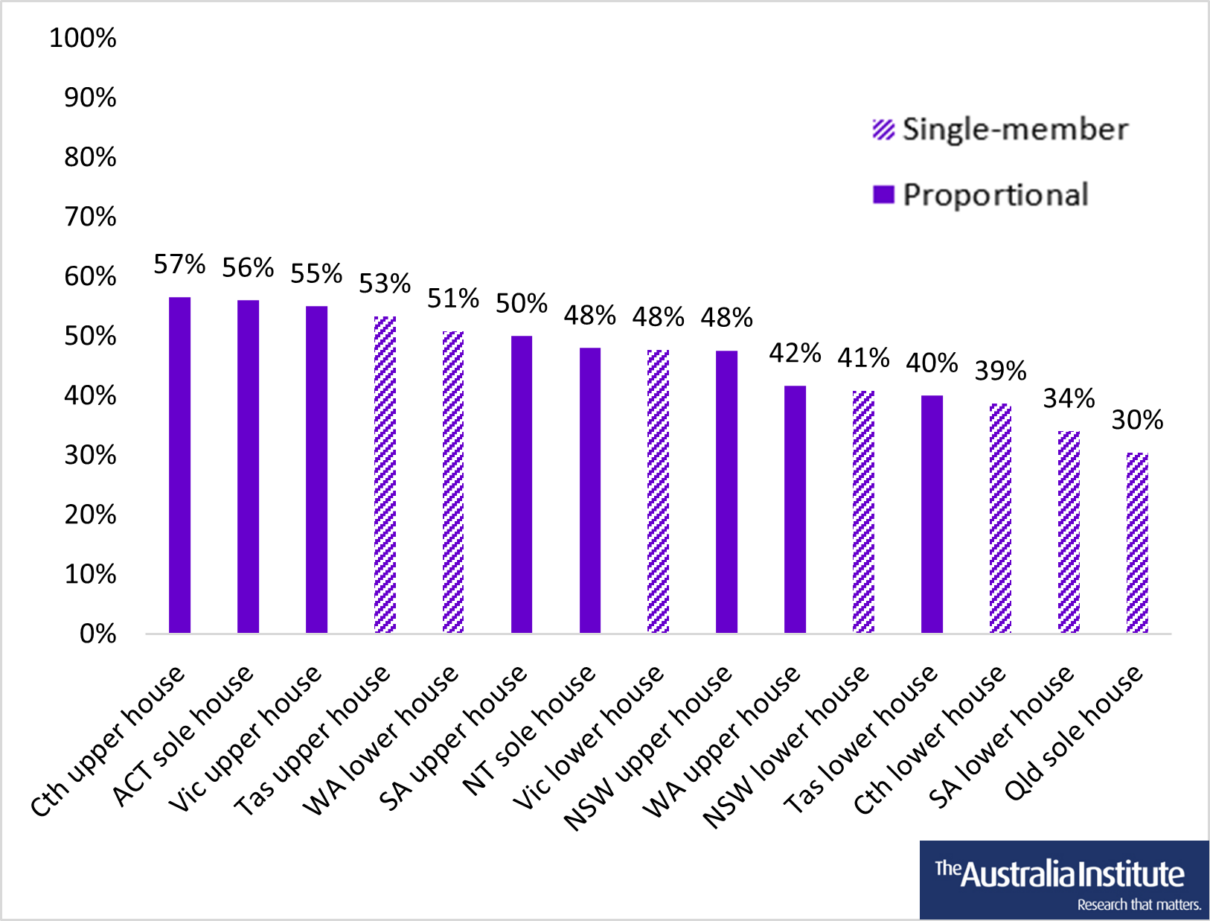

Even today, houses that use proportional representation are closer to gender parity than houses with single-member electorates. As shown in Figure 2 below, the three best houses for women’s representation all use proportional representation; the three worst houses for women’s representation have single-member electorates.

Figure 2: Share of women by house of parliament

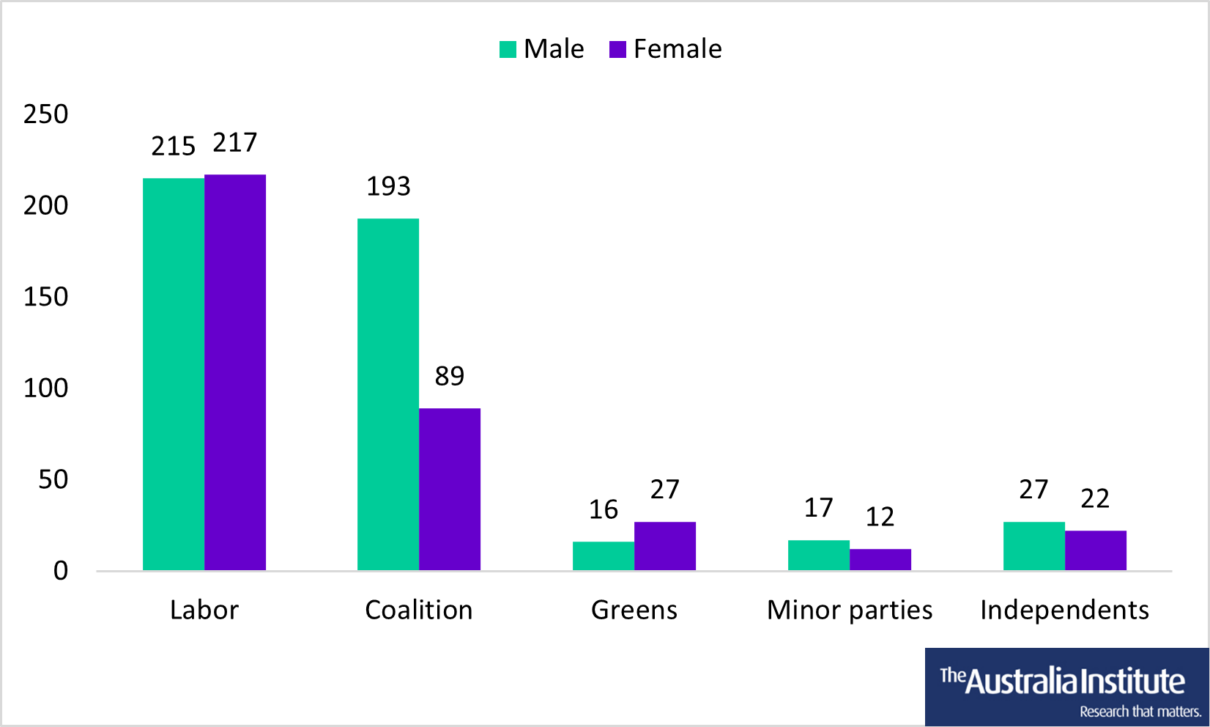

Across the nine Australian parliaments, there are more women than men in only two parties: the Labor Party (50% women) and the Greens (63% women). The community independents, mostly women, were very successful at the 2022 federal election – but across Australia as a whole most independents are men, as are most minor party parliamentarians.

It is in the Liberal–National Coalition where the gender disparity is most pronounced: fewer than one in three Coalition parliamentarians are women.

Figure 3: Female parliamentarians by party

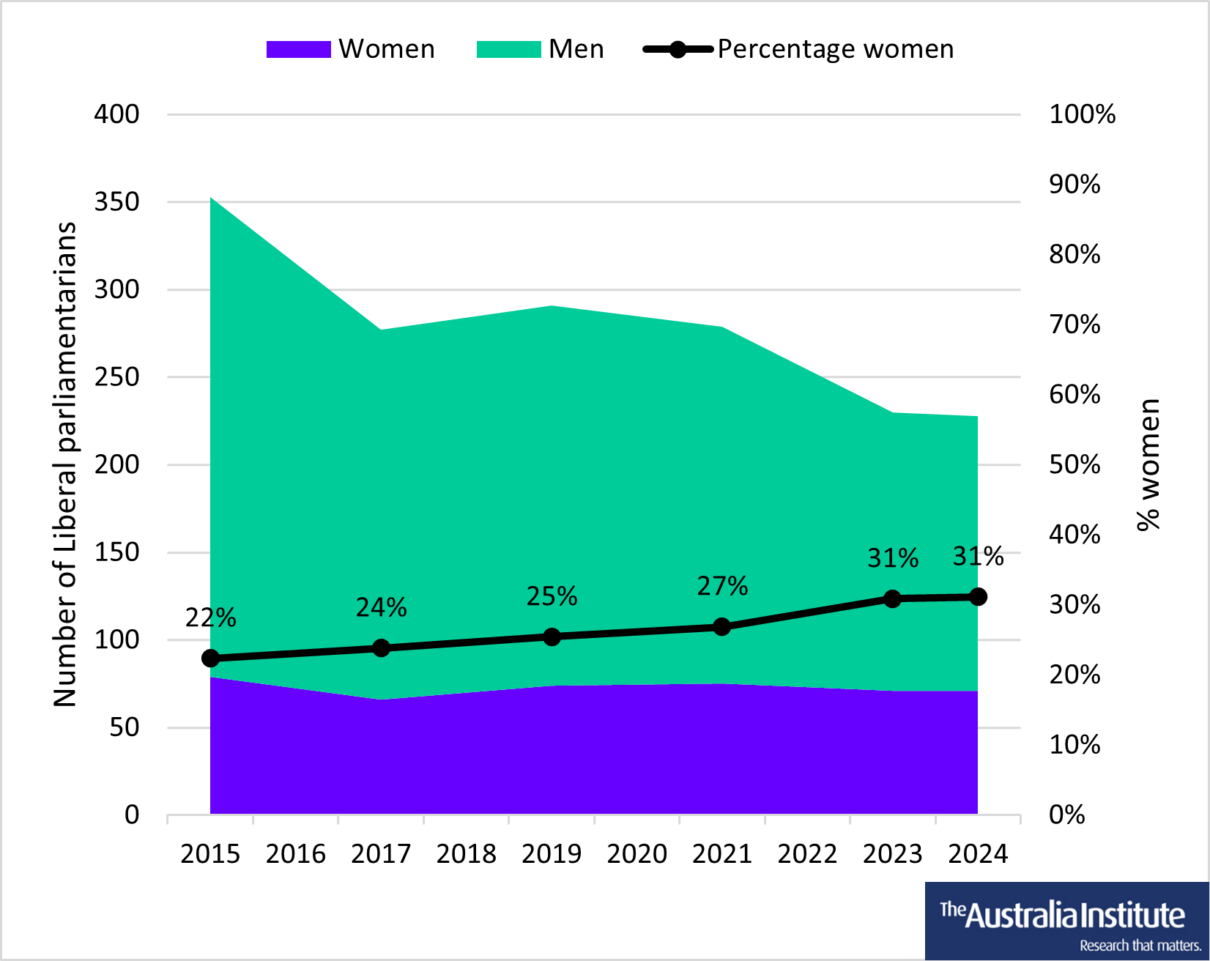

This is surprising, because in 2015 both the Labor and Liberal parties set the same target: for 50% female representation by 2025. (The Liberal Party’s junior coalition partner, the Nationals, do not appear to have a gender representation target.)

With just one year to go, the Liberal Party is still miles away from equal representation for women.

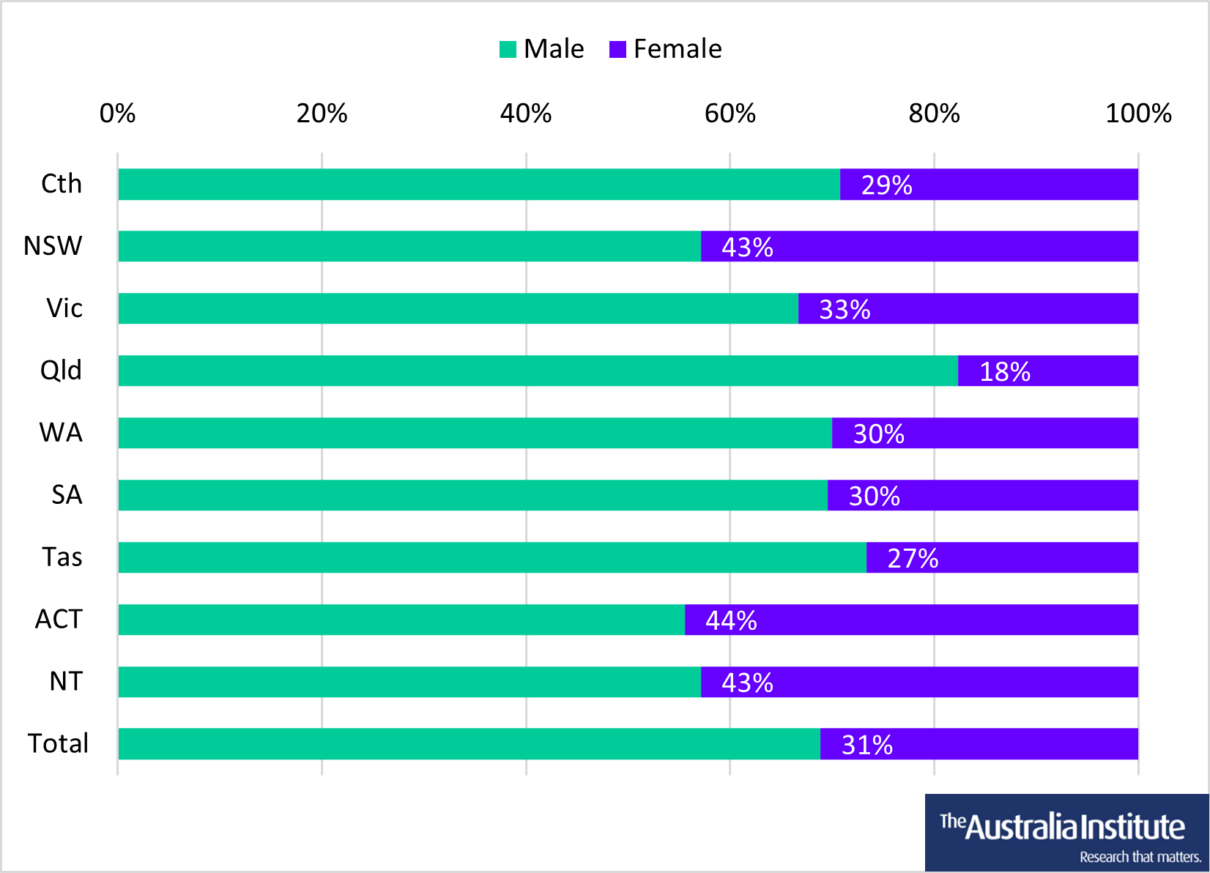

In none of Australia’s nine parliaments do women make up half or more of the Liberal party room. Only 71 out of 228 of Liberal and LNP parliamentarians (31%) are women.

Even if the number of Liberal women doubled overnight, it would still not be enough for the party to meet its 2025 target.

Figure 4: Gender of Liberal parliamentarians, by parliament

The share of Liberal politicians who are women has increased by nine percentage points over the nine years, from 22% to 31%, but in raw numbers there are fewer female Liberal parliamentarians: 71 in 2024 compared to 79 in 2015. The apparent improvement is a result of the collapse in the number of male Liberal parliamentarians, from 274 to 157 over the same period.

Perhaps acknowledging that the 2025 target was out of reach, in 2022 the party’s post-election review suggested a new target: 50% women in the federal parliament in three elections or by 2032. The party’s performance over the last 10 years suggests it is not even on track to do that.

Figure 5: Liberal and LNP women in Australia’s parliaments

The Liberals are keenly aware of their “women problem”, even if they are divided on what to do about it. As Senator Linda Reynolds notes, the Coalition lost 18 seats at the 2022 federal election and: “Of those 18 seats, 14 were won by women.” Similarly, Senator Jane Hume warned: “if we don’t move on with society, we’ll be left behind.”

The Labor Party achieved gender parity two years ahead of its 2025 target; in the federal Parliament women outnumber men in the Labor party room (53% women).

By contrast, the Liberal Party has fewer women in parliaments than it did when it set its target of 50% representation, and its improvement in the proportion of women who are Liberal parliamentarians is a result of so many male Liberals losing their seats.

It is no secret what works. Labor brought in a pre-selection quota for women in 1994 (to be fully realised by 2002), followed by seat quotas in 2012.

But it is not all about quotas. Margaret Fitzherbert, Liberal parliamentarian and author of Liberal women, also attributes Labor’s success in women’s representation to (a) having highly visible champions of women in parliaments; (b) Emily’s List which gives financial and political support to pro-choice candidates; and (c) the party’s rank-and-file culture.

What is a mystery is why the Liberals let Labor establish itself as the major party that represents women.

The Liberal Party used to lead on women’s representation. Eight of the first 10 female federal MPs and senators were Liberals. The Liberal Party (and its predecessor, the United Australia Party) had a greater share of women in the party room than Labor did for the 30 years from when the first women were elected in 1943 to 1974. Gough Whitlam’s “It’s time” win in 1972 included 93 male MPs and senators – and not a single woman. While things soon improved (it was not possible for them to get worse), it would be another three decades before the Labor Party was consistently more gender-representative than the Liberals at the federal level.

Nor were early Liberals opposed to quotas. As former Liberal senator Judith Troeth notes, “from 1944 the Liberal Party had reserved 50 per cent of the Victorian Division’s executive positions for women”. The argument that quotas do not allow women to be selected on “merit” is facile: Coalition Cabinets always have a quota for National MPs.

Change is unlikely to come from within the party membership. Data released by the Menzies Research Centre in 2020 reveals that Young Liberals skew even more male than the rest of the party (65% male versus 57% male).

As noted by Annika Smethurst and Paul Sakkal in The Age, the Liberals have passed up opportunities to bring women into Parliament this term: replacing outgoing parliamentarians Stuart Robert and Marise Payne with two men, and pre-selecting a man for the Dunkley by-election. Days after Jodie Belyea won Dunkley for Labor, Liberal pre-selectors chose yet another man, Simon Kennedy as the Liberal candidate for Scott Morrison’s old seat of Cook.

Australia Institute polling research shows the difficult position the Liberal Party is in when it comes to quotas. In the seat of Dunkley, more voters support quotas for the Liberal Party than oppose them (49% support, 37% oppose), but more Liberal voters oppose quotas than support them (55% oppose, 34% support).

The lack of women’s representation will be noted. Already, women are much more likely to vote for left-wing parties than men are, a trend underway since the 1990s. The same thing is happening around the world, with the Washington Post fretting that political polarisation will reduce marriage rates among young people.

If women aren’t represented in both parties of government, political polarisation and disaffection can only increase. Women make up over half of the Australian population and that should be reflected in our democratically elected parliaments.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Gender parity closer after federal election but “sufficiently assertive” Liberal women are still outnumbered two to one

Now that the dust has settled on the 2025 federal election, what does it mean for the representation of women in Australian parliaments? In short, there has been a significant improvement at the national level. When we last wrote on this topic, the Australian Senate was majority female but only 40% of House of Representatives

Australia’s parliaments closing in on gender parity, in spite of coalition “women problem” – new analysis

New analysis by The Australia Institute reveals that, following the recent federal election, there are now more women than ever in Australia’s nine parliaments, but the coalition’s so-called “women problem” remains.

The election exposed weaknesses in Australian democracy – but the next parliament can fix them

Australia has some very strong democratic institutions – like an independent electoral commission, Saturday voting, full preferential voting and compulsory voting. These ensure that elections are free from corruption; that electorate boundaries are not based on partisan bias; and that most Australians turn out to vote. They are evidence of Australia’s proud history as an