by Richie Merzian

[Originally published on the Guardian Australia, 04 November 2020]

Whether Donald Trump loses or wins the presidential election, the US will officially withdraw from the Paris agreement on Wednesday. The US intention to withdraw was announced in mid-2017 and, exactly one year ago, formal notification was sent to the United Nations. It caps off four years of winding back climate action and the systematic dismantling of pollution safeguards across the country.

The US is the second largest greenhouse gas emitter in the world and played a crucial role securing the 2015 Paris agreement by finally reaching compromise with the world’s largest polluter, China. More than 10 years of negotiations among 195 countries, where every word and every comma was debated and agreed to by consensus, culminated in their joint commitment. That is right – consensus among every nation of the world. The US is now the only country to pull out.

But there is hope for the climate, and the landmark agreement.

If Joe Biden takes the Oval Office, on the day of his inauguration, 20 January 2021, he can formally ask to rejoin the Paris agreement. It takes one year to pull out but only 30 days to sign up. However, regaining membership to the agreement is just the beginning. The divergence on climate policy between the Democratic and Republican candidates is huge – possibly the widest divide between the two platforms – and while Trump questions global warming, Biden has the most ambitious climate policies of any presidential candidate (exceeding those of Barack Obama).

First, Biden will lock the US into net zero emissions by 2050. Not an ill-defined target some time in the second half of the century, like the Australian government’s, but a 30-year target. A target that means putting coal, oil and gas on a downward trajectory, and bringing total global CO2 emissions under a net-zero target to over 60%, including major importers of Australian coal and gas – China, Japan and the Republic of Korea.

Within his first 100 days, Biden has committed to convene a climate world summit to directly engage the leaders of the major carbon-emitting nations of the world to persuade them to join the United States in making more ambitious national pledges, above and beyond the commitments they have already made. From the US, we could see a new, more ambitious emission reduction target than its underwhelming 26-28% by 2025 (if that sounds familiar, it’s because Australia has the exact same underwhelming target range but for 2030, and without the desire to improve it).

Importantly, Biden will pursue countries seen as “cheating” on climate action, using “America’s economic leverage and power of example”. Given the Morrison government’s insistence on using leftover carbon credits to avoid any credible emission reductions over the next decade – dubbed by the former UN climate chief Christiana Figueres as “cheating” and by numerous Australian law professors as legally baseless – Australia may be a target of that pursuit.

Australia and the US might also be at odds over financial support for climate action in developing countries. Biden’s campaign promises include meeting the US climate finance pledge, of which $2bn to the Green Climate Fund is still outstanding. Prime minister Scott Morrison pulled Australia out of the Green Climate Fund in 2018 during an interview with Alan Jones and has resisted calls since from our neighbours in the Pacific to rejoin.

While presidential office is key, if Democrats take a majority of Senate seats their capabilities on climate would grow fast. The president, Senate and key states could see the US move quickly – even this year.

And much like the climate leadership shown by states and territories in Australia that are all signed up to net-zero by 2050 targets, a number of US state governments have already banded together to take climate action under Trump. According to the America’s Pledge report, sub-national action makes it possible for the US to cut emissions by 37% by 2030. And despite Trump’s best efforts to revive the coal industry, more coal capacity (37GW) has been retired under his presidency than during Obama’s second term (33GW). The US consumed more energy from renewables than coal in 2019, for the first time in over a century, setting the stage for Biden’s promise of a carbon pollution-free power sector by 2035.

This 12 December the Paris agreement turns five. The United Kingdom, which will host the next UN climate conference, will mark the occasion with an ambition summit. And while Scott Morrison has resisted calls from the UK to do more on climate, it may be harder to resist similar calls from the US.

Morrison claims, “Our policies won’t be set in the United Kingdom, they won’t be set in Brussels, they won’t be set in any part of the world other than here.” I wouldn’t be so sure. When former president Obama pressured the Abbott government to do more on climate change in 2014, it had an impact. Let’s see what happens when Washington calls again.

• Richie Merzian is director of the climate & energy program at independent think-tank The Australia Institute @RichieMerzian

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Why a fossil fuel-free COP could put Australia’s bid over the edge

When the medical world hosts a conference on quitting smoking, they don’t invite Phillip Morris, or British American Tobacco along to help “be part of the solution”.

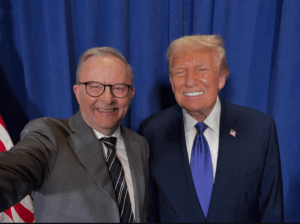

Can Albanese claim ‘success’ with Trump? Beyond the banter, the vague commitments should be viewed with scepticism

By all the usual diplomatic measures, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s meeting with US President Donald Trump was a great success. “Success” in a meeting with Trump is to avoid the ritual humiliation the president sometimes likes to inflict on his interlocutors. In that sense, Albanese and his team pulled off an impressive diplomatic feat. While there was one awkward

Climate target malpractice. Cooking the books and cooking the planet.

As the Albanese government prepares to announce Australia’s 2035 climate target, pressure is mounting to show greater ambition.