By Richard Denniss, Chief Economist at The Australia Institute.

[View this article in the Australian Financial Review]

Having abandoned the principles of small government, the right of Australian politics are now urging Australia to embrace Donald Trump’s attack on international agreements. Is there any institution these so-called “conservatives” aren’t willing to wreck in pursuit of short-term political gain?

When Tony Abbott signed up Australia to the Paris Climate Agreement, he committed to reducing our emissions by 26 to 28 per cent. Our former PM went on to say that, “unlike some other countries which make these pledges and don’t deliver, Australia does deliver when it makes a pledge”. Well, not if our backbencher-in-chief gets his new way.

While Mr Abbott has been quick to confess his ignorance of the details of the international deals he signed, he has been slow to reveal the extent to which not just his bureaucrats, but his ministers were running rings around him. Both former climate minister Greg Hunt and current foreign minister Julie Bishop bragged about Australia’s determination to join a group of countries known as the “Coalition of High Ambition” whose goal was to push for more radical emission reduction goals than those agreed to at Paris. Did our then PM not know about this?

Leaving aside the issue of how deeply misled our former Prime Minister was when he committed Australia to a course of action in front of the world, what would it mean for Australia to embrace the “Abbott doctrine” of foreign policy and simply abandon treaties and promises on the basis that circumstances had changed? If we take Donald Trump’s lead on climate agreements should we take his lead on trade agreements as well?

The first problem, to quote Frank Underwood, is that “the nature of promises is that they remain immune to changing circumstances”. Australia is a signatory to agreements ranging from Free Trade Agreements to the ANZUS treaty, in which Australia, New Zealand and the US have pledged to come to each other’s defence. Such treaties are almost always signed in good times in the hope that they can be relied upon when circumstances change. If Australia embraces a “flexible approach” to such commitments, then presumably we can expect our allies and trading partners to do likewise.

Second, if we take Donald Trump’s lead on climate agreements should we take his lead on trade agreements as well? As prime minister, Tony Abbott made much of his ability to complete bilateral trade agreements; he was also an enthusiastic advocate for multilateral agreements such as the Trans Pacific Partnership. But these days Donald Trump is threatening to rip up deals like NAFTA and has started tariff wars with his trading partners. If we embrace the Abbott doctrine in relation to climate agreements, should we follow suit on trade and tariffs as well?

Third, while it is true that Trump’s position on climate policy is of global significance, it is not true that without US support the world will stop acting on climate change. Trump’s retreat on climate policy gives China, Europe and other players not just a lot of room, but a lot of reasons, to show global leadership. While the Abbott doctrine suggests Australia’s foreign policy should simply orbit around the current position of the US, most other countries see the game of foreign policy lasting longer than a presidential term of office.

The decision to walk away from Australia’s commitment to the Paris climate agreement has far bigger consequences than who will lead the Liberal Party of Australia in a few years. As a small, open economy, Australia has spent decades influencing the shape and culture of multilateral agreements. If we now believe that it is not just acceptable, but desirable, to walk away from such deals when circumstances change then that really is a new world order.

Once upon a time, those who described themselves as “conservative” tended to place their faith in science, economics and the stability that comes with respect for contracts and promises. But in Australia today conservatives pride themselves on their mistrust of science, their determination to ignore economic advice about the efficiency of carbon pricing and now, it seems, they are willing to shred international credibility in pursuit of domestic political advantage.

Tony Abbott has shown himself to be an incredibly effective political operative at the domestic level. He has torn down opposition leaders and prime ministers, and transformed popular policies like carbon pricing, which once had bipartisan support, into political poison. Now that he has international treaties in his sights, it would be folly to underestimate his ability to normalise the Abbott doctrine. What could go wrong?

Richard Denniss is the chief economist for The Australia Institute.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

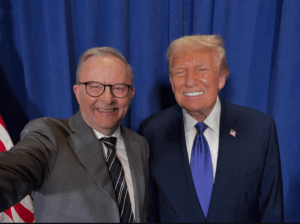

Can Albanese claim ‘success’ with Trump? Beyond the banter, the vague commitments should be viewed with scepticism

By all the usual diplomatic measures, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s meeting with US President Donald Trump was a great success. “Success” in a meeting with Trump is to avoid the ritual humiliation the president sometimes likes to inflict on his interlocutors. In that sense, Albanese and his team pulled off an impressive diplomatic feat. While there was one awkward

AUSFTA: A bad deal then. Even worse now.

Australian consumers paid a high price for John Howard’s determination to sign a ‘Free Trade Agreement’ with the US.

Pots and kettles: Trump trades barbs with China over trade

The global economic outlook is “dim” according to a new report, driven by uncertainty over Trump’s economic and trade policies.