Australia’s newest integrity institution, the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC), will help root out corruption and hold the powerful to account.

The experience of state and territory commissions tells us that the NACC will expose corruption at the federal level — should it exist — and educate politicians, public servants, and the public and act as a deterrent going forward.

But government accountability is about more than just corrupt conduct; day-to-day accountability has been and will continue to be provided by one of Australia’s oldest integrity institutions: the Australian senate.

Since Federation, the senate has reviewed, amended and blocked government bills, inquired into scandals that governments would sooner forget about and ordered the publication of government documents that make public secret information and show the inner workings of government.

Over time, the senate has grown into its accountability role — most notably by introducing the modern committee system in the 1970s. Through committees, senators scrutinise public servants and ministers at Estimates hearings twice a year.

The senate’s ability to hold the government to account is limited mostly by its own will. In an address to the senate earlier this year, we outlined the senate’s vast powers. If it wanted to, the senate could fine or imprison people in contempt of parliament. Doing so would put an end to desultory Estimates answers, late responses to questions on notice and refusals to front up to committee hearings.

Even though such tools are not a realistic prospect in the modern era, it is a useful reminder of the trust and power that the drafters of the Australian Constitution vested in our upper house.

The senate has other tools, including reducing the status of the Leader of the Government in the senate or installing a crossbencher as senate president or deputy.

Parliamentary privilege means senators can table documents without fear of defamation; a privilege used recently by senator David Pocock (and by Andrew Wilkie MP in the House of Representatives) to allow whistleblowers to expose potential wrongdoing without falling foul of Australia’s defamation laws.

In practice, the greatest power of the senate is the one it owes to its status as a co-equal legislature: the senate can block the government’s legislative agenda until the government accounts for itself. The senate has sometimes done this to force the government to produce documents it would rather keep secret; more often, the senate baulks.

While the Albanese government has shown some admirable improvements in transparency, the interests of the government and the parliament will never perfectly align.

It is difficult to stand up to the government of the day, which has immense power behind it and claims a popular mandate. Senators should be heartened by polling the Australia Institute conducted earlier this year. Six in 10 Australians agreed that when the senate and the government disagree on whether the government has to hand over information, the senate should insist on its interpretation.

The NSW legislative council shows just how effectively upper houses can hold the government to account. Earlier this year, suspicions were raised about the appointment of former NSW deputy premier John Barilaro to a post-politics position as US trade commissioner — a role he created when in office.

But the full details of the appointments process only came to light because the Council conducted an inquiry into the appointment, allegedly a “present” for Barilaro, and refused to accept the department holding back key documents — calling an emergency sitting over three weeks ahead of its scheduled times.

Had the legislative council not held firm, the Barilaro saga could easily have been a political footnote without documentary and eyewitness evidence. Instead, the truth came out. Barilaro stepped down as trade commissioner and the trade minister, Stuart Ayres, also resigned.

How many stories are waiting to be told, if the Australian senate were to flex its muscles? However good a government, there will always be missteps and moral errors. Not all will be within the scope of the NACC. For the others, we need a muscular senate to ask hard questions and hold the government’s feet to the fire when it refuses to answer.

Bill Browne is the director of the Democracy & Accountability program at the Australia Institute. @Browne90

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

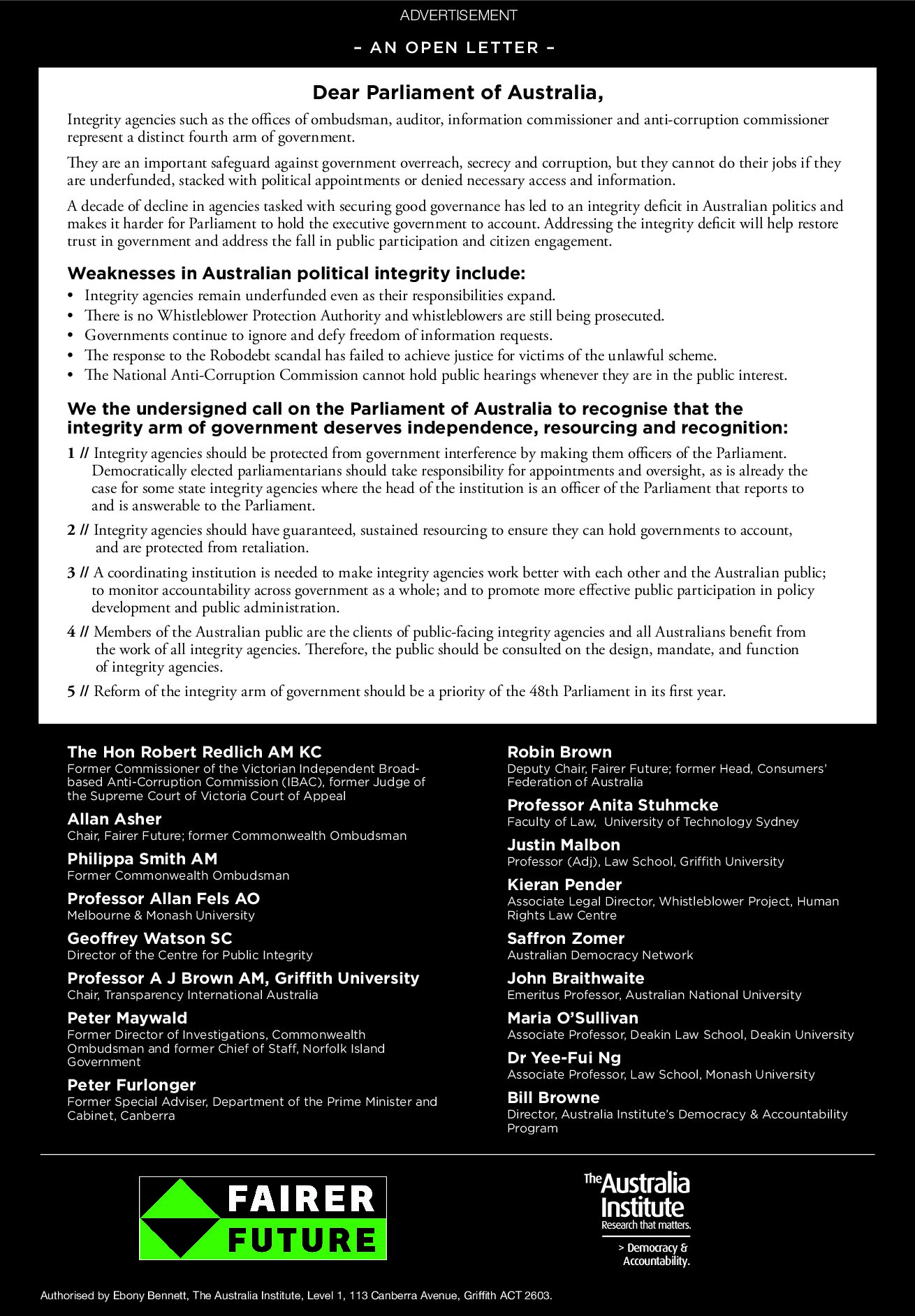

Open letter calls on newly elected Parliament to introduce Whistleblower Protection Authority, sustained funding for integrity agencies to protect from government pressure.

Integrity experts, including former judges, ombudsmen and leading academics, have signed an open letter, coordinated by The Australia Institute and Fairer Future and published today in The Canberra Times, calling on the newly elected Parliament of Australia to address weaknesses in Australian political integrity. The open letter warns that a decade of decline in agencies

A Blueprint for Democratic Reform

Crossbench MPs have joined The Australia Institute to launch a new report outlining potential democratic reforms for the next Parliament.

ANU’s latest scandal shows us why transparency is so important, and where to start

Governance at Australia’s universities is in a dire state.