What is the PRRT?

Gas extraction is often lauded by the industry as the ‘backbone of the Australian economy’, but the actual revenue collected from one of the main taxes on the industry falls staggeringly short of what most people would expect. Find out why this is the case – and what we can do to fix it.

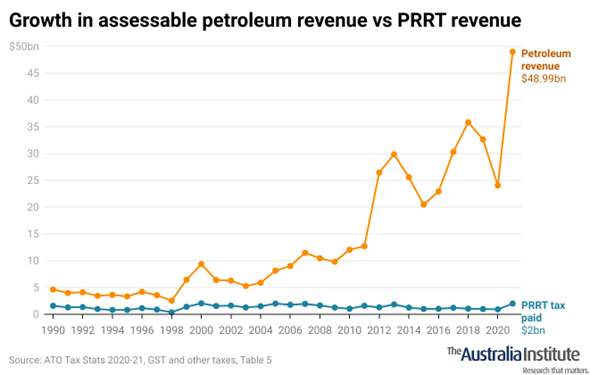

There’s been a lot of talk in Australia about the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax (PRRT). In his address to the National Press Club, Richard Denniss pointed out that “the Commonwealth collects more revenue from HECS fees than it gets from the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax”. But what is the PRRT, how does it work (or why doesn’t it work), and what can we do to fix it?

What is the PRRT?

The Petroleum Resource Rent Tax is a tax introduced in 1988 to ensure Australians benefit from the oil and gas that we collectively own. It was originally designed for oil extraction, but these days principally applies to offshore gas fields.

As a ‘resource rent tax’ it places a 40% tax on rents related to the extraction of natural resources of petroleum, gas and condensate.

Wait. What is a rent? Isn’t that to do with housing?

In this context, “rent” is a fancy economics way of saying super or excess profits. So when you see “petroleum resources rent tax”, think of a super profits tax on oil and gas.

Normal profit is the profit rate needed for the business to keep operating. But a ‘super profit’ or a ‘rent’ is when profit exceeds this normal rate. It indicates something weird is going on in the market.

For example, it might indicate the business has established a monopoly and is now the only seller of the good. More usually though, a ‘rent’ arises when natural resources, such as petroleum, are extracted. This is because the presence of resources and how difficult and costly they are to extract differs across the world.

For instance, Saudi Arabia’s oil extraction is relatively cheap as the oil is light, onshore, close to the surface, and needs little refining, whereas extracting oil in Canada’s Alberta oil sands is expensive, requiring energy-intensive processes to extract heavy bitumen from the sand and then convert it to crude oil.

The price paid for resources such as oil is determined globally by the world’s supply and demand. These prices will roughly equal what it costs to extract the resources from the costliest places, because Canada will not extract oil if it does not receive a price that makes this profitable.

This means that places with lower extraction costs will make higher profits, since they will be paid the high global price whilst themselves having low costs of extraction. These extra profits are ‘rents’ or ‘super-profits’.

Australia is relatively well endowed with hydrocarbon deposits that are easily extracted and processed, so companies can expect to earn these super-profits or rents from extracting Australia’s oil and gas; the PRRT is intended to tax these super-profits and ensure the Australian people, not just multinational corporations, benefit.

So how does the PRRT work?

This is where it gets a bit complicated, but stick with us.

Theoretically, the ‘rents’ associated with oil and gas only arise when they are found and pulled out of the ground. This is because this is the part of the process for which costs are likely to differ across the world due to geological differences, whereas (at least theoretically) processing can happen anywhere.

For this reason, the PRRT is designed to apply only to exploration for and extraction of oil or gas. It does this by only applying at the ‘taxing point’: either when the gas or oil is sold, or when it is transformed into something else sellable, such as liquified natural gas (LNG).

This is easy to calculate if the company that extracts the gas, then sells it to another company to turn into LNG. But the problem with the PRRT is usually the same company extracts and transforms the gas into LNG.

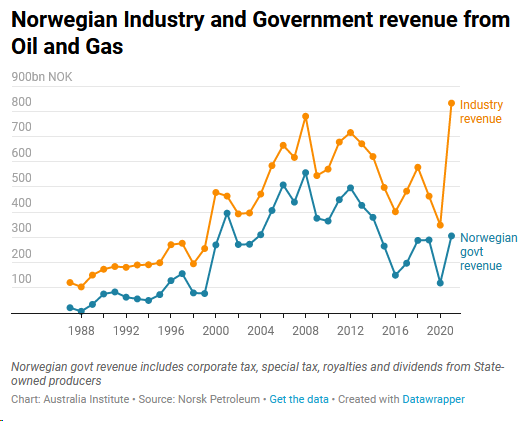

At his National Press Club address, Richard Denniss called out the fossil fuel industry, “in Norway, they tax the fossil fuel industry and they give university education to their kids for free. In Australia, we subsidise the fossil fuel industry and we charge our kids a fortune to go to uni.” ABC News affirmed Australia Institute research that said the Australian Government collects more money from HECS than it does from the PRRT.

Why is that a problem?

The PRRT was designed mostly to apply to oil but now that gas and especially LNG is the big industry, the PRRT’s complicated design have made it much easier for companies to avoid paying PRRT.

Because the ‘rent’ or ‘super-profits’ bit of oil and gas is meant to happen at the exploration and extraction stage, the PRRT tries to only tax this and not processing. But gas needs a lot more processing than oil, and in Australia, the same company is usually responsible for both extraction and processing.

This means that gas companies use a formula to calculate how much the gas is ‘worth’ before it is liquefied into LNG. The formula they are allowed to use means that, by some estimates, only about half of the ‘rent’ ends up being taxed.

Even worse, this formula also appears to allow companies the flexibility to understate how valuable the gas is before liquification (which is taxable) whilst overstating the value created by the liquification process (which is not taxable).

Yeah, that sounds bad

Don’t worry… it gets worse!

Because the tax is not supposed to distort the decision of whether or not to invest, the PRRT is designed to only tax profits after all the costs of building the gas project are recovered, lowering the risk for investors. If a company has more deductions than it can claim for in one year then leftover expenses can be ‘carried forward’ and used as deductions in the future tax bills.

Why is that bad?

The PRRT allows for capital expenses, such as the huge and expensive equipment needed to build an offshore oil rig, to be an immediately ‘deductible expenditure’ (a tax write-off). That means the companies already have a massive amount of things they can use to deduct from their PRRT tax liability.

Secondly, if these expenses exceed revenue, the difference can be carried forward from one year to the next. While normal corporate taxes also allow for tax losses to be carried forward, PRRT differs in several ways including by:

- Allowing capital outlays and exploration as deductions and

- A thing called ‘uplift rates’ to be applied.

Uplift rates? That sounds like one of those complicated tax things that are important.

Yes, “uplift rates” work similarly to interest rates. For example, if a company carries forward $1 million of expenses, a 10% uplift rate would mean that $1.1 million could be deducted from the next year’s tax bill. If this is carried forward again, $1.21 million would be deducted in the next year, and on and on. This means the expenses carried forward can keep growing- a bit like how compound interest increases saving in bank deposits.

That means companies continue to have the ability to offset their profits and not have to pay as much PRRT because they can reduce their profits, so it looks like they are not actually making a super profit.

Gas requires very large capital investments, larger than oil, and it takes several years before gas can be harvested and profits are made. The company can immediately deduct these capital expenses and then receive generous uplift rates. This means that gas companies can carry forward considerable expenses, which mount each year as the uplift rates are applied.

The end result is that when the company finally starts selling the LNG and making money, these deductions have grown considerably, substantially reducing the amount of PRRT they need to pay.

So, the system is pretty much rigged in the favour of gas companies??

Yes!

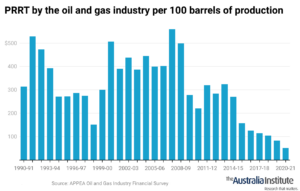

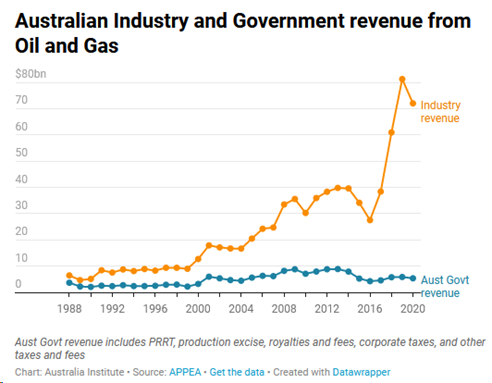

Oil and gas companies have been making huge and growing revenue from exploiting our oil and gas, while the PRRT consistently raises very little money.

Other government taxes and charges don’t do much better.

Despite the gas industry taking off since the 2000s, total Australian revenue from oil and gas has remained stubbornly low. This included when gas profits exploded following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

These profits were known as ‘windfall profits’ as they were not predicted by the companies. As they were unexpected, they would not have formed part of investment decisions and likely could have been taxed without impacting future investment.

Do any other countries do a better job at taxing oil and gas, or is it too hard?

Other countries do a lot better job than Australia. Norway for example is a huge producer of oil. But the Norwegian Government has consistently been able to capture significant amounts of the revenue from their oil and gas industry and benefitted during booms, allowing them to pay for things like free university education and nearly free childcare.

It sounds like we should fix the PRRT. Is the government doing anything about it?

Unfortunately, the only change adopted by the Albanese government has been to “limit the proportion of PRRT assessable income that can be offset by deductions to 90 per cent”. What this means is that if the company calculates they have $10 million in taxable profits and $10 million in expenses (either carried forward or new), they can only deduct $9 million and will still owe tax on $1 million.

At the 40% tax rate, they would have to pay $400,000.

Isn’t that a good change?

It sounds better than it really is. While it does mean that the government might get revenue sooner – in the above example, the company is now paying $400,000 in that year rather than $0 – it is unlikely that the overall taxes paid by the industry will change as the remaining $1 million of expenditure will still be carried forward into the following years and deducted.

Think of it this way: imagine you pay $100 for electricity each month and then receive a $100 voucher. Ordinarily, you would use this voucher to pay your bill for one month and then directly pay your full bill the next month. Now imagine the company has a rule that you can only pay for 50% of the bill with vouchers. In the first month, you pay $50 with the voucher and $50 in cash; the next month, you again pay $50 with the voucher and $50 with cash.

The electricity company received cash sooner, but the absolute amount they received did not change.

So, what can be done?

There are lots of different reforms that could make the PRRT work properly, or at least better. These include:

- raising the rate of the PRRT above 40%;

- improving the way that the gas is valued before liquification;

- reducing the uplift rates, meaning carried forward expenses don’t grow so quickly or

- inserting triggers to tax at a higher rate when companies make windfall profits.

But too often, this discussion gets confused in the details, not the outcome. We need more tax revenue; the specific nature of that change is secondary.

The Australia Institute is calling for an increase to the PRRT so that Australians get a fair ‘rent’ from the fossil fuel industry.

Will these changes hurt the economy?

Whenever tax reform of Australian mining is mentioned, commentators (many of them lobbyists) will raise concerns that this will stifle investment.

However, in the case of gas, Australia has large accessible reserves and is a safe country in which to invest and work. Claims that companies will go elsewhere ignore the fact that the gas is here!

Also, in the case of oil and gas extraction, discouraging further investment is not actually a bad thing.

We are in an ongoing climate crisis, and any new or expanded fossil fuel projects will create more emissions, which means we are unable to meet our climate goals. In these circumstances, a dual focus on wringing revenue from these projects and gradually phasing them out while discouraging further investment is sensible.

The current way gas is taxed creates an incentive to produce more greenhouse gas emissions.

We should tax the things we want less of. We need less gas and more renewables. We should tax the gas industry more to help fund the transition to renewables.

You can sign the Australia Institute’s petition here.

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Yes, the government collects more money from HECS than it does from the petroleum resource rent tax.

We need to tax things we want less of and subsidise things we want more of. Right now with PRRT and HECS, we’re doing it the wrong way round.

Explainer: How the government collects more from HECS/HELP than the PRRT

The government consistently collects more from people repaying their student debts than it does from the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax.

The gas industry is laughing at us as they make more money but not more tax

Despite soaring production and revenues the gas industry is not paying more tax